On Violence in the South: Nonviolent Protest

On Violence in the South: Nonviolent Protest

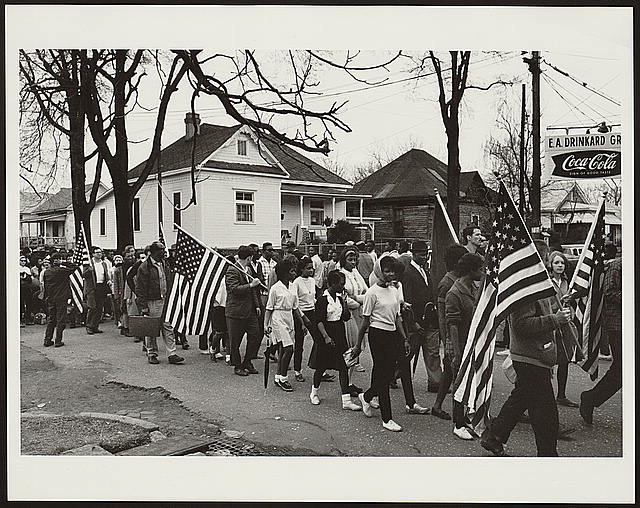

As a response to violence and the issues it raises, and how people have opposed it, the Center is running a series of entries from the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture volume on Violence, published in 2011. So far this week we’ve featured entries on Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Jessie Daniel Ames, and antilynching activism. Today, an article by Charles Reagan Wilson on nonviolent protest.

Nonviolent Protest (Civil Disobedience)

Nonviolent protest goes far back in American history. The Boston Tea Party was civil disobedience that led to national independence. The First Amendment to the federal Constitution, with its protection of free speech and the right to assemble, established the legal context for nonviolent protest. Henry David Thoreau famously went to jail for refusing to pay a tax to support the Mexican War. Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad too escaped slaves to freedom, combating slavery without violence. The women’s rights movement used nonviolent strategies, leading to the right to vote in 1920. The labor movement used strikes and boycotts in seeking better working conditions and higher pay. Such individuals and groups have long resisted injustice or worked to achieve social change without violence, but the combination of organized mass resistance and nonviolent strategies reached a new level of philosophical coherence and sociopolitical effectiveness in the 20th century. The U.S. South became the site for one of the most significant uses of nonviolent protest to effect social change through the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Nonviolent resistance is anchored in two separate traditions. One is the religious insistence that harming another person is always immoral and that loving one’s enemies can transform individuals and societies. The second, a political tradition, organizes economic, social, and political power to force changes in laws and policies regarded as unjust. Dissenters to unjust policies organize sources of power outside of government to compel official authorities to recognize the need for change. Nonviolent direct action efforts in the South were linked to national organizations in the early 20th century, those supporting pacifist activities and those promoting labor union organization.

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) was an international pacifist organization that began its work in the United States in 1915. During World War II it broadened its efforts beyond international affairs to address the problem of racial segregation in the nation. As early as the 1940s FOR members wanted to establish chapters in the South to launch a nonviolent campaign against Jim Crow. A. J. Muste, the FOR national secretary, and Bayard Rustin and James Farmer, field organizers for Muste, began in that decade articulating a philosophy and practice of nonviolence aimed at challenging the South’s segregated social system. They drew from such books as Richard B. Gregg’s The Power of Non-Violence (1944) and Krishnalal Shridharani’s War without Violence (1939), the latter of which came from a disciple of Mohatma Gandhi and detailed his procedures for organizing social change coming out of the struggle for Indian national independence from the British. FOR’s approach was through appeals to social morality, based in civil dialogue and lived example, to win over those entrenched defenders of segregation. Muste and his pacifist colleagues expanded the definition of pacificism from a message to a means of action to achieve reconciliation after the end of injustice.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) championed nonviolent direct action from its emergence as a separate organization out of the FOR in 1942. FOR provided paid staff, nonviolence training, and information on social activism across the South through the 1950s for CORE and other civil rights groups. CORE remained an informal, decentralized organization in its early days, with James Farmer becoming the first national CORE chairman in 1943 and remaining with the group until 1966. It succeeded in integrating movie houses and roller skating rinks in northern and western cities in the 1940s and developed relationships with white and black students in the upper South to plant the seeds for later use of nonviolent resistance. CORE pioneered modern nonviolent direct action for civil rights with sit-ins in the 1940s and a freedom ride, called the Journey to Reconciliation, in 1947. Still, one observer of race relations in the region, Constance Rumbough, noted in 1948 that “most Southern leaders think that the nonviolent direct action technique is not advisable in this area.”

CORE persevered in establishing a network of chapters across the South, with 24 by 1960. CORE provided guidance to the Greensboro, N.C., students who launched a sit-in at a lunch counter in that same year, and the group initiated the “jail-in” strategy, of activists serving out jail terms when arrested, rather than paying bail. “Jail, no bail” attracted considerable national publicity and became a significant direct action technique in the civil rights movement. In May 1961 CORE launched the first Freedom Ride of the movement, sending seven white and six black activists on bus rides into the South. Harassment, intimidation, fire bombings, beatings, and prison sentences met the freedom riders, but they succeeded in bringing an end to segregated seating in interstate travel. CORE was one of the sponsors of the seminal March on Washington in 1963.

CORE represented the expansion of Christian pacifism to civil rights struggle, but another source for nonviolent protest in the South was the labor movement, with Highlander Folk School the most direct institutional connection between labor and civil rights. Labor organizers had worked in the South since the late 19th century to organize industrial workers in coal mines, textile mills, timber camps, and other work places but had met violent resistance from corporate owners and government authorities. Founded in 1932 by Myles Horton, Don West, and the Rev. James A. Dombrowski, Highlander was an adult education facility that at first specialized in training leaders of the labor movement in Appalachia and in nurturing appreciation and preservation of mountain cultural values. It achieved modest success in contributing to organizing workers in areas surrounding the school’s east Tennessee location in Grundy County in its first decade. During the 1940s the school’s faculty concentrated on unionizing textile workers in Tennessee and the Carolinas, directing labor education programs throughout the South, and developing residential workshops that promoted a racially integrated and politically engaged labor movement.

In 1953 Highlander launched new initiatives to encourage racial integration in the South, holding its first workshop on school desegregation in the year before the landmark Brown v. the Board of Education Supreme Court decision. Hundreds of people attended these workshops, which quickly made Highlander the educational center of early civil rights efforts. Literacy programs addressed the needs of blacks prevented to vote by state literacy requirements. Highlander music director, Zilphia Horton, adapted an old gospel song, which had been sung by striking tobacco factory workers in 1946, into the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” In July1955 Rosa Parks, prior to her role in touching off the Montgomery Bus Boycott, came to Highlander for a workshop, later speaking of that experience as the first time she had lived in “an atmosphere of equality with members of the other race.” Highlander trained key civil rights figures in nonviolent direct action techniques in the mid and late 1950s, including Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel, Bernard Lafayette, Ralph Abernathy, and John Lewis. In the early 1960s, when student sit-ins began, college students gathered at Highlander to consider the next stages of the black freedom struggle. Regarded as truly subversive by authorities—even if nonviolent in philosophy—the state of Tennessee revoked Highlander’s charter in 1962 and confiscated its property.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott became the crucible that brought connections between nonviolent direct action protest and civil rights together. Representatives from national organizations long working in civil rights came to Montgomery in 1955 to offer advice, ideas, and resources to local leaders. A committed pacifist, Bayard Rustin had long been a key figure in the FOR/CORE alliance, holding positions in both organizations and participating in the Journey of Reconciliation in 1947, for which he was arrested in North Carolina and spent a month on a chain gang. Afterwards, he went to India to meet with Gandhi’s sons and came away blending Gandhian nonviolent protest into his pacifism, all of which he shared with Montgomery leaders. The Rev. Glenn E. Smiley, a white official with FOR, also came to Montgomery to visit with the emerging leader of the bus boycott, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Smiley, a Texan who was a devout believer in Gandhi’s methods, carried an array of books about nonviolence for King, who confessed to Smiley that, at that point, he could not claim to know much about Gandhi’s principles. Some leaders of national organizations hoped to control the boycott, but seeing the energy and organization at the local level they came to provide funding and ideas instead of control. Perhaps the most significant civil rights leader of the early 1950s, A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, observed that Montgomery leaders had “managed thus far more successfully than any of ‘our so-called nonviolence experts’ a mass resistance campaign and we should learn from them rather than assume that we knew it all.”

The immediacy of leading the Montgomery boycott surely led Martin Luther King Jr. to new understandings of the sources of nonviolence resistance and their applicability to the movement. King had long been interested in how religion could be used to combat social problems, especially the segregation he had grown up with in Atlanta. The black church had given him focus on Christian love, which he now combined with his growing appreciation of how Gandhian nonviolence could provide strategies for protest. In 1957 King identified nonviolent techniques for racial justice as “creative forms,” including mass boycotts, sit down protests and strikes, sit-ins, refusals to pay bail for unjust arrests, mass marches, and prayer sessions. King embraced Gandhi’s concept of satyagraha, which he defined as “truth-force,” “love-force,” or “soul-force.” “I came to see for the first time that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom.” As leader of the bus boycott, he found his thoughts driven back to the Sermon on the Mount and the Gandhian method of nonviolent resistance.” As he observed, “Christ furnished the spirit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method.”

King put forward key principles of nonviolence. He stressed it was “not a method for cowards; it does resist.” It sought not to humiliate its opponents but to win their friendship and respect. Its attack was directed against the forces of evil and not the individuals caught in those forces. Nonviolent protest should avoid a violence of spirit within protestors as well as avoiding external physical violence; in struggling for human dignity, protestors should not give into bitterness and hate. Finally, “the method of nonviolence is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice.” King based much of his thinking in this regard, not only on Gandhi’s writings but on the idea of Christian love, as embodied in the concept of agape. King defined this as a kind of love wherein individuals love people “because God loves them and here we love the person who does the evil deed while hating the deed that the person does. It is the type of love that stands at the center of the movement that we are trying to carry on in the Southland—agape.”

King admitted the difficulties at first of convincing the Montgomery boycotters of the value of nonviolence. “There was always the problem of getting this method over because it didn’t make sense to most of the people in the beginning.” King and other leaders used their mass meetings “to explain nonviolence to a community of people who had never heard of the philosophy and in many instances were not sympathetic to it.” In the early days of the movement, the phrase “Christian love” was used by boycotters, reflecting the specifically Christian outlook that informed African Americans in Montgomery. “It was Jesus of Nazareth that stirred the Negroes to protest with the creative weapons of love,” King noted. As time passed, “the inspiration of Mahatma Gandhi began to exert its influence.” King praised Montgomery’s blacks for their willingness to grapple with a new approach to the crisis in race relations. His experience in Montgomery, he later wrote, did more to clarify my thinking on the question of nonviolence than all of the books that I had read.” For him, living through the protests, “nonviolence became more than a method to which I gave intellectual assent; it became a commitment to a way of life.” More than a strategic expedient, nonviolence became for King and others in the movement a philosophy “that men live by because of the sheer morality of its claim.” Through countless sermons, lectures, classes, interviews, and publications, at endless mass meetings, protest events, and public gatherings, King became the nation’s foremost exponent of nonviolence resistance, a philosophy grounded in the specific experiences of protest on southern soil.

Out of Montgomery came two organizations embodying nonviolent resistance—the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). King and others founded SCLC in 1957 to coordinate civil rights direct action protests across the South and to offer a reform voice to the nation, with nonviolence and civil disobedience central to its mission. The organization offered leadership training workshops and citizenship education programs. It held voter registration drives and undertook a major campaign to attack segregation in Birmingham, Ala., which came to a head in 1963. James Bevel, who had trained at Highlander and became a leader in the Nashville student sit-ins in 1961, became the central strategist and conductor of the “children’s crusade,” a march of black young people that crystallized the city’s black community in support of the protests. James Lawson, who had been a Methodist missionary in India, observed Gandhi’s nonviolent methods, and became committed to nonviolence as a governing philosophy in the 1940s, first met King in 1957 and soon came to chair SCLC’s direct action committee and later became director of its nonviolent education work. Lawson called in 1961 for a “nonviolent army” to challenge segregation, pushing the organization in ever more militant directions. The same was true for another key activist, Ella Baker, who became interim director of SCLC when it was founded and was important in combining nonviolent philosophy with calls for economic justice.

Baker was a bridge from the SCLC to the establishment of SNCC, which became another central civil rights organization built around nonviolence. Baker called a meeting at Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., in 1960 to encourage student sit-ins, and out of that meeting came the student-led group whose members participated in Freedom Rides to end segregation in interstate travel and supported voter registration drives and citizenship education projects, including a crucial role in Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964. SNCC members in the late 1960s came to question the effectiveness of the interracial coalition that had long been central to civil rights work, and they rejected the nonviolent philosophy and tactics with the rise of the Black Power movement. The organization disbanded in 1970.

Since then, many social movements, from environmental activists to antiabortion advocates, have employed nonviolent civil disobedience in support of their goals in the South, but doing so without the breadth and depth of the civil rights movement’s embrace of nonviolence in the decades of the 1950s and 1960s. The Martin Luther King federal holiday often is the occasion for continued public reflection on the principles of nonviolence.

Charles Reagan Wilson

University of Mississippi

David Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1986); John M. Glen, Highlander: No Ordinary School (1996); Wesley C. Hogan, Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC’s Dream for a New America (2007); Joseph Kip Kosek, Journal of American History (March 2005); Rhonda Mawhood Lee, Journal of Southern History (May 2010); August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, CORE: A Study in the Civil Rights Movement, 1942-1968 (1973); Aldon D. Morris, The Origins of the Civil Right Movement: Black Communities Organizing for Change (1984); Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash, eds., Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Nonviolent Action from Gandhi to the Present (2009); James M. Washington, ed., A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King Jr. (1991).