On Violence in the South: Antilynching Activism

On Violence in the South: AntiLynching Activism

As a response to violence and the issues it raises, and how people have opposed it, the Center will be running a series of entries from the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture volume on Violence, published in 2011. So far this week we’ve featured entries on Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Jessie Daniel Ames. Today, an article by Karlos K. Hill of Texas Tech University on Antilynching Activism.

Antilynching Activism

In 1901, Mark Twain, the prolific writer and observer of American culture, sarcastically noted that America had become the “United States of Lyncherdom.” For Twain, lynchings were becoming so commonplace that he predicted that the number of lynchings per year would exceed the 500-mark by 1903 and that a spectacle lynching would occur in downtown New York City. Although Twain’s prediction did not come to fruition, lynching did gain widespread approval, which inspired a number of activists to organize antilynching campaigns during the first half of the 20th century.

Lynchings were extralegal public executions meant to punish alleged criminals and deviants. What distinguished lynchings from simple murders was that they were typically carried out by a group with the intent that the execution would be viewed by a collective either during the execution or afterwards. Therefore, a lynch mob’s desire for the public consumption of extralegal violence was one of lynching’s distinguishing features.

The antilynching movement emerged in response to the dramatic rise of lynching in the 1890s and the American public’s seeming acceptance (even glorification) of lynch mob violence. From the beginning, women played crucial roles in antilynching crusades. Ida B. Wells emerged as a national and international celebrity for her outspoken denunciations of white-on-black lynchings and the rape of black women by white men. Wells’s antilynching activism sprang from witnessing the lynching of Thomas Moss, a successful black grocer, and several other black men in Memphis in 1892. Wells penned three significant antilynching pamphlets that provocatively challenged white southerners’ justifications of lynching. In particular, Wells’s pamphlets challenged the idea that black men were increasingly raping white women and that lynching was needed to deter black criminality and restore white womanhood. Instead, Wells argued that lynchings were an attempt to deprive blacks’ economic opportunity and citizenship rights. Through her tireless campaigns to alter public opinion, Wells laid the foundation for future female antilynching activism.

Most notably, in 1930, Jesse Daniel Ames founded the Association for Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching (ASWPL). Ames’s primary message was that lynchings denigrated white womanhood rather than upheld it. Ames believed that if white women openly rejected lynching as a chivalrous practice, they would delegitimize lynching and over time lynchings would cease. By the end of the 1930s, dozens of ASWPL chapters had been organized throughout the South. The ASWPL’s success in organizing white southern women against lynching lent credibility to antilynching rhetoric among southern whites—credibility that black antilynching activists such as Ida B. Wells had never been able to achieve.

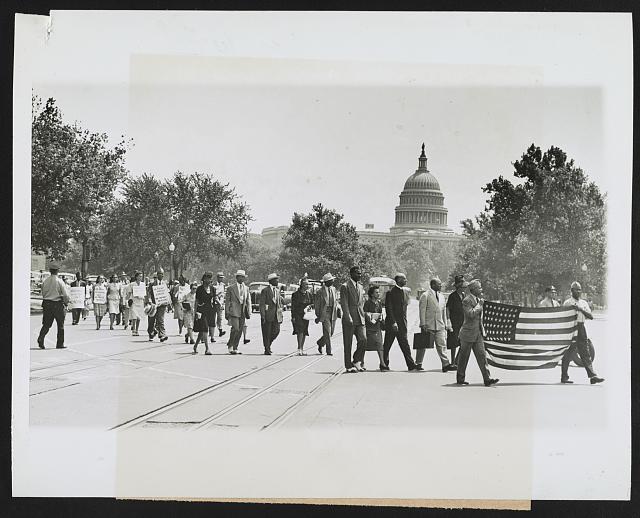

While Ida B. Wells and the ASWPL did much to alter how lynchings were perceived, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) led the most sustained assault against lynch mob violence. Between 1920 and 1950 the NAACP tirelessly campaigned for federal antilynching laws. The NAACP contended that southern localities routinely failed to punish lynch mob participants and the police officers who allowed lynchings to occur. The organization reasoned that if federal antilynching statues were adopted, it would make punishing lynching more likely and as a result fewer whites would participate in lynch mob violence. The NAACP’s lobbying efforts paid dividends. On three separate occasions (1922, 1937, and 1940), the House of Representatives passed antilynching legislation; however, each time southern lawmakers defeated antilynching legislation in the Senate. Although federal antilynching laws were never adopted, the NAACP’s activism placed greater pressure on southern states to pass antilynching laws and southern localities to punish whites who aided and abetted lynch mob violence.

Karlos K. Hill

Texas Tech University

Crystal Feimster, Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching (2009); Amy Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940 (2009); Robert Zangrando, The NAACP Crusade Against Lynching, 1909–1950 (1980).