On Violence in the South: Criminal Justice through the Civil Rights Era

On Violence in the South: Criminal Justice through the Civil Rights Era

This week, in a response to violent events across the nation, the Center has shared a series of articles from the 2011 Violence volume of the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Today, we close the series with a look at criminal justice in the South through the civil rights era by Christopher Waldrep of San Francisco State University. So far this week we’ve featured entries on Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Jessie Daniel Ames, antilynching activism, and nonviolent protest.

Criminal Justice through the Civil Rights Era

For much of their history, white southerners controlled crime with a prejudiced criminal justice system and extralegal violence. To black southerners, white southerners themselves acted criminally with their slavery and biased law enforcement. On the frontier between these two conceptions of crime and justice lay the true central theme in southern history: skepticism about whether due process—law in its regular course of administration through courts of justice—could effectively control crime. Both black and white southerners questioned whether the other side’s darker impulses could be effectively controlled by abstract due process rules enforced bureaucratically. Doubt about the effectiveness of due process standards in the face of crime characterized the South, but that misgiving became the hallmark for all of American culture.

Race influenced white southerners’ attitudes toward crime not immediately, when the first Africans landed in North America in 1619, but later, after slavery became the primary system for controlling labor. This happened around 1660, changing criminal justice, permanently setting the South on its course toward extralegal violent crime control. In 1669 the Virginia legislature wrote its toleration for extralegal crime control into law with a statute entitled “An act about the casuall killing of slaves.” This law exempted slave owners from prosecution should they “chance” to kill a slave during the “extremity” of “correction.” Since most crime control happened outside the formal institutions of government, such a law was necessary to safeguard from prosecution ordinary citizens using violence to control their black property.

White southerners understood their responsibility to control the South’s black population as collective and best expressed through the slave patrol. Local governments organized and operated patrols. But the system had its roots in the more informal and private efforts organized by colonists in the Caribbean and Latin America. In 1661 the first comprehensive slave code in Barbados expected all whites to order and govern Negroes. This slave code also articulated whites’ conviction that African descent implied a criminal character. The authors of the Barbados statutes feared blacks as heathens and brutes, people inherently dangerous. This detailed slave code might suggest a rigorous police state, but historians have found the opposite. In Barbados slaves evaded the law, trading in goods stolen or otherwise. In large measure, policing slaves meant controlling—with only limited success—this illicit trade.

South Carolina copied the Barbados slave code and white patrollers watched for signs of trouble: secretive slave gatherings, slaves without passes, violations of the curfew. What had been a voluntary effort in Barbados became mandatory in South Carolina and the other American states. In 1696 South Carolina’s legislature passed a more coercive law, organizing white men into squads to better whip and jail slaves from the countryside found in town on Sundays. Slaves wandering around on Sundays profaned Sabbath, but they also exchanged information outside white supervision, creating opportunities for insurrection.

The growth of towns in the South helped define and shape the nature of policing. Southern towns and cities organized the first uniformed police in America. Charleston introduced a police force, the city guards, in the 1780s. Savannah, New Orleans, Mobile followed later. These cities responded to complaints about slaves congregating in towns, engaged in criminal activities, buying liquor and guns. White people complained that urban areas furnished slaves a refuge, places to hide from pursuing masters. The city guards patrolling those places wore uniforms and carried weapons. They received salaries rather than fees. They patrolled at night with a reserve force available during the daytime. They formed autonomous organizations because cities pleaded with legislatures for freedom from county interference. New Orleans had its own autonomous force after 1805. In 1832 Virginia cities won the right to organize their own patrols. One place to trace the origins of professional policing in America is in these urban slave patrols.

Professionalizing law enforcement increased through the late antebellum period when southern states increasingly subjected criminal trial court procedures to greater scrutiny. In the 1840s and 1850s southern state supreme courts increasingly tried to impose due process standards on trial courts. In Mississippi, the High Court of Errors and Appeals insisted that local magistrates inform slave suspects of their common law right to remain silent. In Mississippi, trials carried out with biased jurors had to be done over; even slaves had a right to an unbiased jury. There were limits to these innovations. As late as 1849, Virginia still tried slaves charged with felonies before special courts of oyer and terminer, sitting without a jury and proceeding without a grand jury indictment. Slave defendants had lawyers, paid for by their owners, but the lawyers received no more than $25. Most scholars agree that due process protections really guarded the rights of the owner, not the slave defendant. Slaves received due process protections only when they stood accused of murder, rape, or arson, all capital crimes. Slave trials involving these serious crimes should be seen as condemnation proceedings, some scholars say. Due process protected the property owner rather than the defendant.

Such efforts to impose due process standards on slave trials actually changed the overall criminal justice system very little. At the end of slavery, southern courthouses still saw very few slave defendants, even in jurisdictions where slaves vastly outnumbered white people. For a criminal justice system dependent on slavery to control crime, emancipation was a catastrophic blow. White southerners brought their fears of African Americans into the postemancipation era. There are no regionwide statistics, but violent crime must have increased with the end of the Civil War. Normal mechanisms of policing, which included slavery, the patrol system, and the states’ court systems, broke down. Confederate guerrillas and criminal gangs took advantage; when the federal government reimposed martial law in 1867, military patrols found they had to arrest white horse thieves more often than black criminals. Despite this, white southerners acted on their racial fears with a system of discriminatory laws northerners condemned as Black Codes. Mississippi passed the first of these laws in November 1865 the rest of the South soon followed. These laws continued the pass system, requiring that African Americans carry proof of employment, punished slow working as “vagrancy,” and authorized every white person to question blacks they encountered on the public highways. Blacks could not leave contracted employment prematurely nor could they testify in court against white persons. Mississippi’s law created county courts meeting continually to process the expected wave of black criminality. County courts could administer a quick beating; imprisonment would have deprived landlords of needed labor.

Such brutal laws produced demands by northerners for federal supervision of southern criminal justice procedures. When Congress assembled in December 1865, members debated how to bring order to the South as well as whether and how to intervene on behalf of the freed people. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, defining citizenship and outlining the rights of citizens. Citizens could enter into contracts, buy and sell property, and, most important of all, testify in court, regardless of race. Federal authorities could prosecute crimes committed by state officers acting “under color of law.” The Civil Rights Act also authorized federal judges to transfer into U.S. district courtrooms state ordinary criminal cases involving black people, if state courts discriminated. Congress, then, threatened the states’ criminal justice systems. If the southern states persisted in their overt discrimination, they risked losing control of their criminal justice system to federal judges. Every southern state but one quickly backed down, repealing their black codes. Kentucky persisted, denying blacks the right to testify against whites until federal prosecutors took over a murder case against John Blyew and George Kennard, charged with murdering a black family on 29 August 1868. Two witnesses survived the attack, but they were both African American and Kentucky law forbade their testimony in state court. Their testimony in federal court led to the convictions of Blyew and Kennard. The two convicted men appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Between 1871, when the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Blyew v. United States, and 1883, when the Court decided the Civil Rights Cases, the justices decided a series of cases designed to protect states’ rights and prevent the imposition of due process standards on the southern states by federal judges. In Blyew v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Blyew and Kennard, overturning their convictions, deciding that federal authorities should not have taken Blyew and Kennard’s case out of state court. The justices wrote a strikingly narrow decision to justify this outcome. Witnesses to a murder, the justices said, could not be victims of discrimination because they had no interest in the case. Nor could the victims be subject to discrimination since they were dead. These decisions guaranteed that criminal justice in the South would get little federal supervision. After the Supreme Court’s decision in this and other criminal cases, southern states excluded African Americans from their juries, did not seriously investigate, prosecute, or try persons accused of lynching, and often refused to extend criminal justice services to African American citizens.

Throughout the 19th century, and into the 20th, white southerners saw vigilantism as integral to their criminal justice system, a vital supplement to the slower and less effective processes administered by courts. When black defendants did go to trial, charged with crimes against white persons, mobs sometimes crowded the courtroom, intimidating jurors and court officers. This happened to white defendants as well. In 1915 the Supreme Court considered mob intimidation in the sensational Leo Frank case. The manager of an Atlanta pencil factory, Frank had been convicted in state court for murdering Mary Phagan. Frank claimed his trial had been dominated by a mob and asked for a federal writ of habeas corpus. The U.S. Supreme Court rebuffed Frank, seeing in his petition an attempt to unlawfully expand federal power. The Court charged that Frank’s lawyers sought to deny Georgia the opportunity to supervise its own trials. Such a doctrine, the Court warned, would prevent the states from effectively repressing and punishing crime.

In 1923 the Supreme Court reversed itself and decided that in trials where the mob so dominated the proceedings as to sweep aside the judge and jury, federal courts could step in and try the case. Oliver Wendell Holmes, dissenter in the Leo Frank case, wrote the opinion of the Court. It would, however, be hard to call Moore et al. v. Dempsey a turning point. After 1923 southern courts continued to hold their trials much as they always had, with all-white juries and amid persisting reports that mobs continued to crowd courtrooms, intimidating juries and court personnel.

In 1940, when the Federal Bureau of Investigation began researching reports of lynching, the agents reported that white southerners believed that they had a right to lynch black men accused of rape so long as they acted before an arrest. Once the accused person went into jail, many white persons thought the mob should step back, but not before. In fact, even that caveat did little to limit mob violence. Some sheriffs and deputies turned prisoners over to mobs, holding them only long enough for the mob to organize itself.

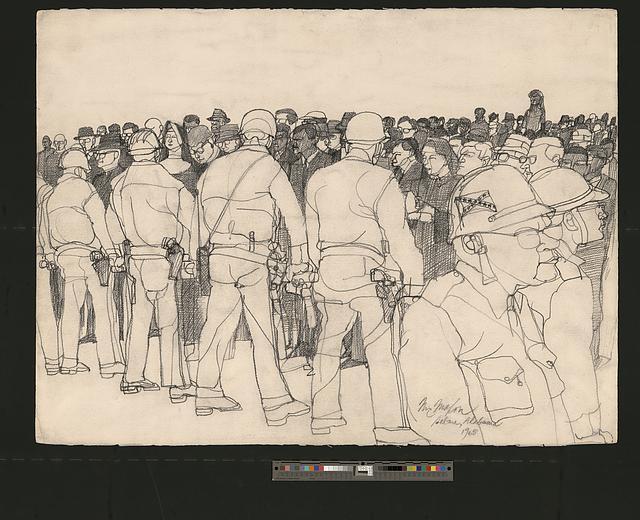

During the 1960s and afterwards, southern courts asserted themselves more aggressively. Progressive political leaders insisted on more professional justice. The South became less tolerant of vigilante groups, including the infamous Ku Klux Klan. In part this development can be attributed to the political success of African American political candidates after the 1965 Voting Rights Law. Thereafter, black southerners became mayors and sheriffs across the South. At the same time, the U.S. Supreme Court increasingly demanded greater due process in criminal trials. Southerners, black and white, had reached a new social agreement that professional law enforcement and not private vengeance should control crime. In the popular culture, though, the image of the heroic vigilante acting to control crime outside the rule of law persisted, having become a national phenomenon, no longer only the central theme for the South.

Christopher Waldrep

San Fransico State University

Edward L. Ayers, Vengeance and Justice: Crime and Punishment in the 19th-Century American South (1984); Peter Bardaglio, Reconstructing the Household: Families, Sex, and the Law in the 19th-Century South (1995); Michal R. Belknap, Federal Law and Southern Honor: Racial Violence and Constitutional Conflict in the Post-Brown South (1987); Charles C. Bolton and Scott P. Culclasure, eds., The Confessions of Edward Isham: A Poor White Life of the Old South (1998); Robert D. Goldstein, Stanford Law Review (February 1989); Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (2001); Michael J. Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality (2004); Thomas D. Morris, Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619–1860 (1999); Dennis Rousey, Policing the Southern City: New Orleans, 1805–1889 (1996); Judith Kelleher Schafer, Slavery, the Civil Law, and the Supreme Court of Louisiana (1994); Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (1992); Mark V. Tushnet, Slave Law in the American South: “State v. Mann” in History and Literature (2003); Gilles Vandal, Rethinking Southern Violence: Homicides in Post-Civil War Louisiana, 1866–1884 (2000); Christopher Waldrep, Roots of Disorder: Race and Criminal Justice in the American South, 1817–80 (1998).