A New Encyclopedia Tribute to Muhammad Ali

A New Encyclopedia Tribute to Muhammad Ali

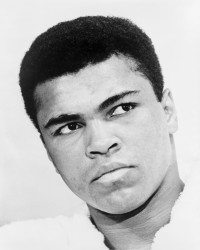

Muhammad Ali died this past Friday, on June 3. The following biographical essay by Jimmy Thomas on the boxing great and civil rights leader was included in the Gender volume of The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture.

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali

(b. 1942) Boxer.

“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” are the words most often attributed to Muhammad Ali, the Olympic gold medalist and three-time World Heavyweight Champion boxer. Graceful yet powerful, as his catchphrase implied, Ali became just as famous for his stance against racial intolerance and his outspokenness against American society—in which he felt black men and women were treated as less than equal to whites—as he did for his outstanding success in the ring. Named Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. when he was born—Ali’s father was named after the ardent nineteenth-century, Madison County, Kentucky, abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay—Ali’s destiny as social critic seemed fated from birth. Ironically, however, Ali changed his name to Muhammad Ali after embracing the Nation of Islam, insisting that Cassius Clay was his “slave name.”

Ali began his boxing career as a twelve-year-old boy in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. When his new bicycle was stolen, he reported the theft to the first police officer he found, crying and claiming that he would beat up whoever it was who had stolen the bike. As it happened, that officer was Joe Martin, a boxing coach at the Columbia Gym in Louisville. Martin told the distraught boy, “Well, you’d better come back here and learn how to fight,” thus beginning his and Ali’s trainer/boxer relationship.

“I was Cassius Clay then,” Ali said years later in a Sports Illustrated story. “I was a Negro. I ate pork. I had no confidence. I thought white people were superior. I was a Christian Baptist named Cassius Clay.” But by the time Ali was a high school senior he had begun exploring Islam, writing a senior paper on Black Muslims that nearly kept him from passing the class. He boxed as an amateur for six years, winning the Light Heavyweight gold medal in the 1960 Olympics in Rome, turning professional that same year and winning his first Heavyweight Boxing Champion title in 1964 against Sonny Liston. Shortly thereafter he changed his name to Muhammad Ali, symbolizing his new identity as a member of the Nation of Islam.

The shift in Ali’s religious faith came at a volatile time in American civil rights history. He became famous after winning the gold medal in Rome, and after winning his first boxing championship and announcing his conversion to Islam, Ali became an outspoken critic of American racial injustice, a message in line with his new Muslim faith. Ali’s obvious prowess in the ring made him a highly visible symbol of black masculinity, and his comments outside the ring became a source of black pride, propelling him into the role of a strong, straight-talking black leader. At a time when violence across the South was raging, Muhammad Ali was speaking out unambiguously against racism, violence, and injustice, and he often preached against social integration as a means to equality: “We who follow the teachings of Elijah Muhammad don’t want to be forced to integrate. Integration is wrong. We don’t want to live with the white man; that’s all.” His rhetoric was often so exaggerated, going so far as to condone lynching as a way to keep the races separate, that he sometimes offended both sides of the race argument, from white supremacists to members of the NAACP.

In 1967, Ali refused to fight in the Vietnam War, claiming conscientious objector status on the basis of his religious beliefs. He later said to a Sports Illustrated reporter, “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs?” As a result of his refusal to serve, Ali lost his boxing license and was stripped of his Heavyweight Boxing Champion title.

In 1970, Ali regained his boxing license, and although he made millions in the ring, he was ostensibly opposed to the sport: “We’re just like two slaves in that ring. The masters get two of us big old black slaves and let us fight it out while they bet: ‘My slave can whup your slave.’ That’s what I see when I see two black people fighting.” Nevertheless, Ali went on to fight in some of the most famous and highly promoted boxing matches in history, such as “The Fight of the Century,” fought in Madison Square Garden against Joe Frasier; “The Rumble in the Jungle,” fought in Zaire, Africa, against George Foreman; and “The Thrilla in Manila,” fought in the Philippines, again against Joe Frasier. Ali lost the first bout by unanimous decision but won the latter two, further cementing his reputation as the epitome of black masculinity.

In time, as public support waned for the war in Vietnam and as the pace of violence against blacks in America slowed, Ali’s antiwhite rhetoric diminished, but his passion for racial justice prevailed. When asked how he would like to be remembered, he remarked, “As a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him and who helped as many of his people as he could—financial and also in their fight for freedom, justice, and equality. As a man who wouldn’t embarrass them. As a man who tried to unite his people through the faith of Islam that he found when he listened to the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. And if all that’s asking too much, then I guess I’d settle for being remembered only as a great boxing champion who became a preacher and a champion of his people.”