W e want the world to know that we no longer accept the inferior position of second-class citizenship. We are willing to go to jail, be ridiculed, spat upon and even suffer physical violence to obtain First Class Citizenship.

- Ella Baker

COUNTER HISTORIES connects the protests and demonstrations of today and yesterday, equipping viewers to ask questions about the role of civil disobedience in the face of systemic racism and injustice.

When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on July 2 of that year, he leveraged the power of the federal government to desegregate places of public accommodation engaged in interstate commerce. Restaurants, including lunch counters, which were early flashpoints in the Civil Rights Movement, could no longer legally operate under Jim Crow dictates.

With vinyl spinner stools and long slabs of linoleum, lunch counters were designed as everyman spaces, where lawyers and laborers sat side by side to eat griddled burgers and fries. As COUNTER HISTORIES makes clear, those Southern spaces had not previously lived up to that ideal.

In 2014, the Southern Foodways Alliance worked with longtime collaborator Kate Medley to produce a series of films that mark the 50th anniversary of this landmark legislation. We commissioned five films from five teams across the South. SFA is proud of their good work and the collective spirit it represents.

Our goals are to put the restaurant desegregation struggles of the 1950s and 1960s in historical context, make clear what lessons were learned in the process, and ask what work remains to be done toward the welcome table ideal. These films share stories from our Southern past. And they demonstrate the relevance of these events in the present day.

COUNTER HISTORIES encourages viewers to think beyond the demonstrations. We see and hear protesters talk about how their actions set the stage for a relatively integrated Southern present. We look and listen as historians ground these events in the broader Civil Rights Movement. We watch activists talk, fifty years later, about how they leveraged moral authority to practice nonviolence and achieve desegregation.

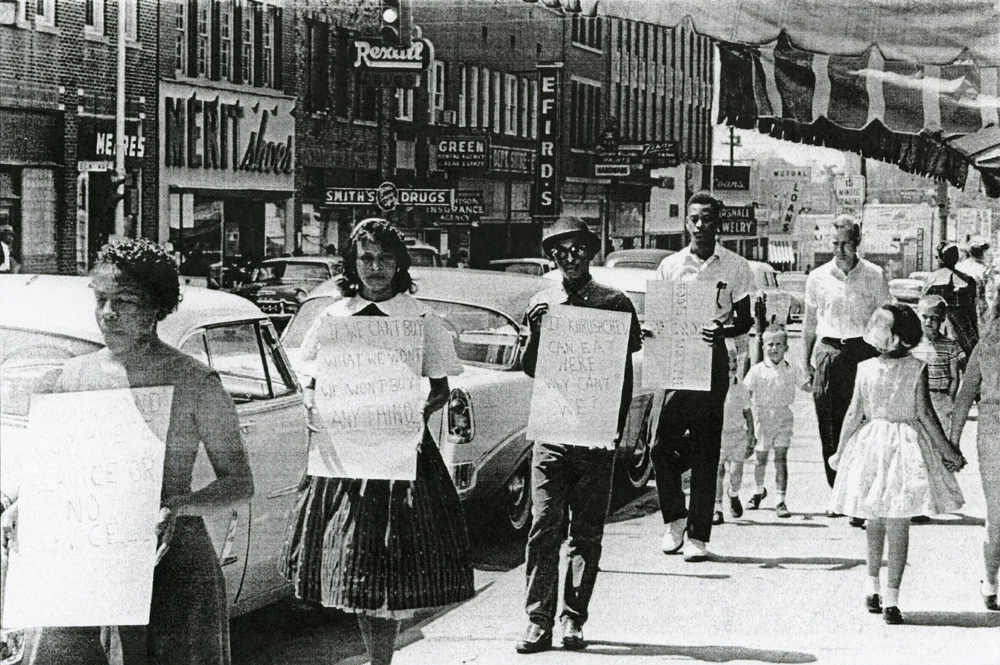

Watch these five films and what you realize anew is how young these men and women were, how well organized they were, and how politely insistent they were. You also recognize that these struggles were not Civil Rights Movement sideshows. They were primary. Decades before social media became a medium for dissent, these young men and women were taking direct and brave action and facing real consequences.

Ella Baker famously declared in 1960 that sit-in demonstrators were “concerned with something much bigger than a hamburger.” Later that year, Baker wrote, summarizing a firebrand talk she gave at the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “We want the world to know that we no longer accept the inferior position of second-class citizenship. We are willing to go to jail, be ridiculed, spat upon and even suffer physical violence to obtain First Class Citizenship.”

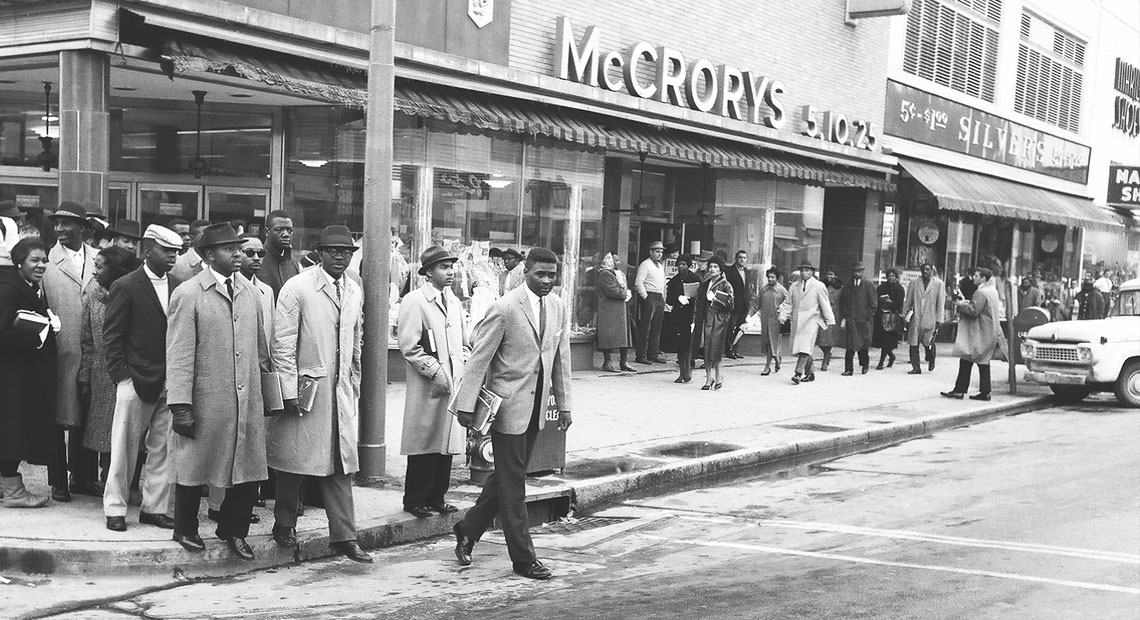

By some accounts, protesters staged roughly one hundred sit-ins during the Civil Rights Movement, stretching across the South from Dallas to New Orleans to Richmond. Many viewers already know about Greensboro, about how the role of lunch counters in the social life of our region began to change in February of 1960, when four black freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College walked into an F.W. Woolworth Company store in that North Carolina town and requested service.

Struggles weren’t restricted to the South. In 1960, the National Council of Jewish Women members visited 200 Tucson, Arizona, restaurants, urging them to end discrimination aimed at African American and Mexican American customers. More than a third refused to comply. But in the South, the struggles were more frequent and more violent. By the end of 1960, more than 70,000 men and women had participated in sit-ins and picket lines. And more than 3,000 had been arrested.

Through COUNTER HISTORIES we also learn:

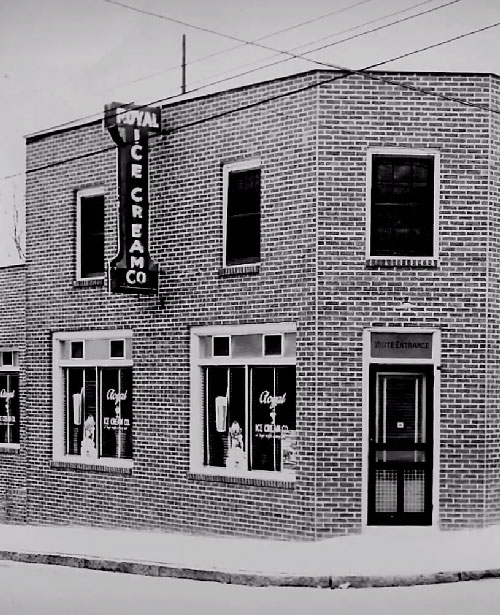

Greensboro was not the first successful Carolina sit-in. Royal Ice Cream Parlor in downtown Durham, North Carolina, was the 1957 site of an early and important action, led by protesters from Ashbury United Methodist Church. Throughout the movement, church leadership proved key.

Nashville, Tennessee, was the intellectual and logistical heart of the movement. Nashville efforts were in works before Greensboro. Wary of violent reprisal, Nashville college students developed protocols: “Do show yourself friendly on the counter at all times. Do sit straight and always face the counter. Don’t strike back, or curse back if attacked. Don’t laugh out. Don’t hold conversations. Don’t block entrances.” Through those protocols, students protected themselves and established mechanisms to drive the movement forward.

Image courtesy of David Wallace

Within two weeks of the Greensboro demonstration, students in eleven cities had staged sit-ins, mostly at lunch counters in downtown department stores. Just across the border from Charlotte, North Carolina, Rock Hill, South Carolina, was pivotal. Most of the protestors there were Friendship College students. The “Jail, No Bail” tactic piloted by the “Friendship Nine” spread rapidly to other protesters who refused to fund city governments that oppressed black citizens.

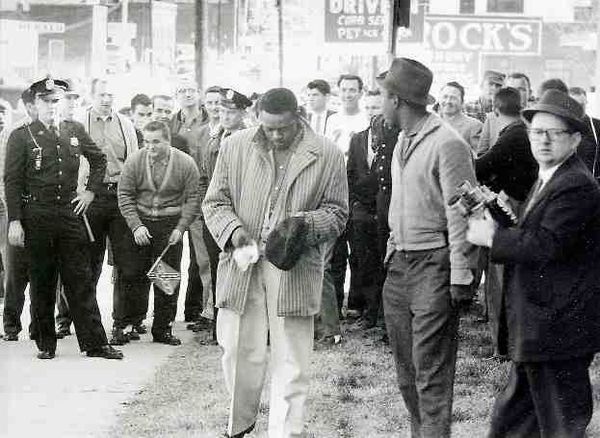

At a time when few white-owned Southern newspapers accurately covered the movement, national press coverage often drove public perception and pushed legislative possibilities. Photos of Robert Fehsenfeld, the proprietor of Dizzyland in Cambridge, Maryland, who smashed eggs on the faces of protesters, made the national news in 1963, showcasing the inhumanity of white mob responses.

Jackson, Mississippi, was the site of the most violent counter-protests of the era. In May of 1963, when an integrated group led by college students attempted to gain service at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in downtown Jackson, a mob of protesters threw salt in their eyes and dumped mustard on their heads. Again, national press coverage brought the struggle into stark relief. Again, students led the drive for equal access to public accommodations.

Watch COUNTER HISTORIES films and you see commonalities in the title sequences. And you glean that each filmmaking team has framed its work in an accessible way. But that’s purposefully where the commonalities end. Each team has taken a different directorial tack, ranging from a traditional documentary dependent on archival footage and participant interviews to experimental re-enactions of pivotal events.

(Photo by Fred Blackwell)

These films ask questions of black citizens. Would you have had the fortitude to join the protests? To lead the protests? These films compel white viewers to ask questions of themselves, too. Which side of the issue would you have been on? Would you have taken a seat alongside black protesters? Or would you have stirred the crowd by tossing epithets and brickbats? What’s more, these films ask questions of today’s youth, no matter their race or ethnicity. What stand will you take to defend our civil rights?

During the summer and fall of 2014, fifty years after the desegregation of lunch counters and other places of public accommodation, another season of social unrest and upheaval has roiled our nation. Sparked by the killing of black men by white police officers, demonstrations and protests erupted. Many were peaceful. Some were violent.

Issues of racism, civil rights, and injustice have proved catalytic again. COUNTER HISTORIES connects the protests and demonstrations of today and yesterday, equipping viewers to ask questions about the role of civil disobedience in the face of systemic racism and injustice.

John T Edge

Director, Southern Foodways Alliance

December 22, 2014