“There was a secret panel in this house,” she said craftily, not telling the truth but wishing that she were.

– Flannery O’Connor, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”

Making believe that I never lost you

But my happy hours I find are so few

My plans for the future will never come true

Making believe, what else can I do?– Jimmy Work, “Making Believe”

1Introduction

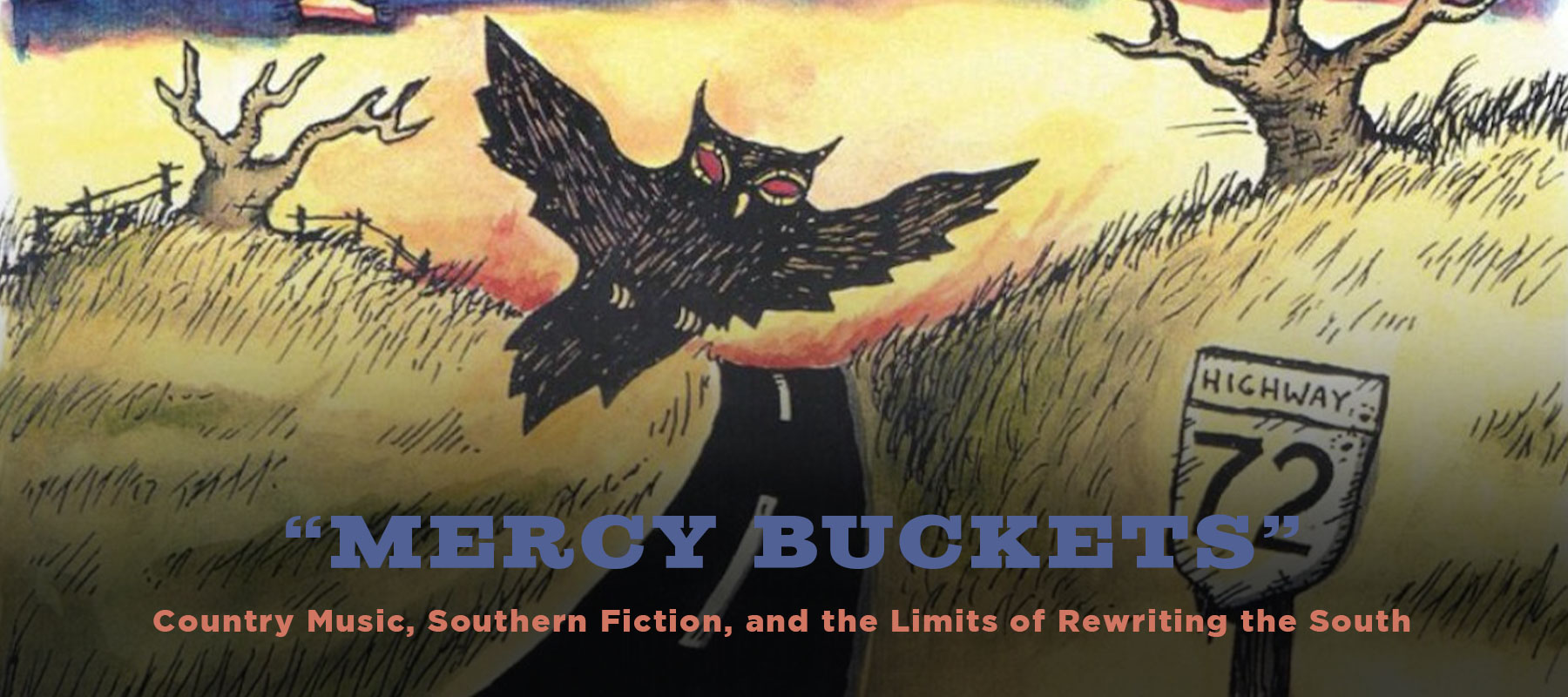

During World War II, GIs began saying “mercy buckets” as an intentional, joking mispronunciation of the French “merci beaucoup.”1 In the 2011 song “Mercy Buckets,” the southern rock and alt-country band Drive-By Truckers rewrite the phrase’s origin by treating it as an idiom of the American South. As might be expected, however, DBT do not reinforce stereotypical notions of the ignorant southern redneck. Instead, songwriter and lead singer Patterson Hood takes the phrase seriously, explaining just what it would mean if bringing someone “buckets of mercy” were a recognized part of southern culture. Hood’s notion of mercy depends on everyday kindnesses, such as a chat, some cash, or a ride home. Drive-By Truckers thus construct a mostly merciful South based in compassionate kindness for people who are struggling in one way or another: “When you’re down and out, I’ll pick you up down at the station / Give your hard times some vacation / And get you headed on your way.”2 Hood thus reimagines southern cultural history by combining the song’s rewording of the French phrase with his own storyteller’s wink. In so doing, he displays a crafty wishfulness that the song shares with a long history of southern cultural production. As seen in the epigraph, for instance, the grandmother in Flannery O’Connor’s 1953 short story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” tells a story that she knows to be a lie, expressing a desire for a different type of history. The speaker of Jimmy Work’s 1955 country standard “Making Believe” also hopes for something better and, like “Mercy Buckets,” this song refers to the personal struggles that cause him to retell his past and rewrite the future.

In this article, I investigate a strand of southern storytelling that pretends the truth of an acknowledged lie. The texts investigated in this essay respond to a more self-consciously pluralistic cultural moment than those mid-century epigraphs do, so it follows that interpreters of southern history work across media and within multiple genres. Scott Timberg demonstrates this range in the Los Angeles Review of Books when he characterizes Hood as “one of the sharpest observers of southern culture and society since C. Vann Woodward, W. J. Cash, and the southern novelists he read as a kid.”3 Timberg links history, songwriting, and fiction to show how Hood fits into the region’s tradition of cultural observation and interpretation.4 Notably, Timberg relates Hood’s songwriting to authors and artists from across the South, which I continue in this article by reading “Mercy Buckets” alongside works by Lewis Nordan, Dorothy Allison, and Jason Michael Carroll. These songs and stories depict a broader, more general South rather than engaging in hyperlocal storytelling, which demonstrates how the merciful lie is a regional response to personal dissatisfaction, trauma, and hard times. Still, because these texts deliver their characters only very conscribed mercies, the merciful lie serves less as a successful reimagination of southern culture and more like a method for audiences to nurture their own compassionate communities.

2Working-Class Southscapes

Drive-By Truckers famously ruminate on “the duality of the Southern Thing” on their breakout album, Southern Rock Opera (2001), exploring the friction between southern iconography and the realities of history and experience.5 Scott Romine has found a similar duality throughout contemporary southern cultural production, arguing that, “time and again in the stories in and about the late South, an opposition between the real and the fake emerges to perform crucial narrative work.”6 Tensions between real and fake emerge in “Mercy Buckets” in the way Drive-By Truckers turn a joke into an idiom but still perform those lyrics as an authentic representation of everyday life. For example, the first stanza tells a story of a mundane but meaningful personal connection:

When all your good days keep getting shorter, count on me

When you’re ’bout twenty cents shy of a quarter, count on me

When you just need a place to hide out for a while

I’ll help you hide the bodies in a little while.

Hood sings in the future tense about the way a fictional idiom helps the song’s speaker define real relationships (Hood has said it’s about his wife and kids).7 In some ways, this is a simulation of southern identity much as Romine develops in The Real South—the narrative comes together explicitly because those tensions extend beyond the personal, with possibilities and metaphors stacking one on top of the other to a more generalized, relatable picture of southern life. But by letting the audience in on the joke, Drive-By Truckers also show the limits of this particular way of rewriting the South. From the listener’s perspective, the narrative doesn’t make “buckets of mercy” become real; they become aspirational. By focusing on stories and songs that identify their lies yet still present them as true stories, this article examines how southern fiction and music consciously play with the “real” and thereby imagine new possibilities for regional culture.

Because they are grounded in the history of the South and southern cultural production, those possibilities are advanced or limited according to race. This article addresses primarily white creators and characters, approaching the texts through Thadious M. Davis’s concept of the “southscape,” which “acknowledges the connection between society and environment as a way of thinking about how raced human beings are impacted by the shape of the land.”8 The songs and stories in this article do not often reference race in an explicit way, as they participate in a cultural landscape that simultaneously hides and highlights racial difference. Still, my focus on white, working-class perspectives is a limiting factor that may be expanded by attention to other musical genres from across the South as well as contextualized among Black folk forms (such as the communal implications of Zora Neale Hurston’s “lies”).9 In tracing music and fiction from the mid-twentieth century to the present, I follow a trajectory of scholarship on performances of race and authenticity in southern music that I anchor in Karl Hagstrom Miller’s and Erich Nunn’s studies on race records, folk music, and the color line in the early to mid-twentieth century.10 The works in this article also respond to the southscape of Amanda Marie Martinez, who examines the reactionary politics underlying country music’s marketing of “redneck chic” in the 1970s: “For a growing number of whites discomfited by the social movements of the 1960s, refuge was alternatively found in the Southern imaginary and the signifiers of white rusticity.”11

Joined by the other songs and stories I examine in this essay, “Mercy Buckets” seeks refuge in both rustic signifiers and the elaborate, winking performance of authenticity. According to Travis Stimeling, this combination appears throughout the Drive-By Truckers’ oeuvre, as musically and aesthetically they pair working-class forms with Southern Gothic tropes.12 The band’s album covers overtly depict Southern Gothic versions of everyday life. Painted by Virginia artist Wes Freed, they feature scenes of highways and headstones, blackbirds and boots. Lyrically, Hood’s vision of the South relies on Southern Gothic exaggerations of the speaker’s willingness to hide bodies, dig graves, and “pay your bail.” But the song also includes mundane mercies such as “a friend to talk to” or an offer to “hold your hand when you’re crossing the street.” Even the gothic references are bound up in everyday generosity: the allusion to violence in “pay your bail if you need it” can be heard as the much more ordinary “pay a bill if you need it”—a clever homophonic play within a song based on them.

Hearing the lyrics like this hinges on the sound of Hood’s Alabama drawl, emphasizing the song’s adherence to southern language patterns. “Mercy Buckets” revises cultural histories, but Hood’s drawl underscores how the song still depends on that culture. In a 2015 essay on southern heritage in New York Times Magazine, Hood describes his songwriting as an explicit attempt to combine fables with the gritty details often marginalized in stories of the South: “I’ve spent the better part of my career trying to capture both the Southern storytelling tradition and the details the tall tales left out.”13 Hood grounds his essay in fractious contemporary conversation about southern identity, as well as the racist histories and implications of symbols like the Confederate flag. Throughout the Drive-By Truckers catalog, Hood’s songs are imprinted with and respond to these stated and unstated historical connections, and scholars have described how the band roots their progressivism in southern culture.14 On Go-Go Boots, specifically, “Mercy Buckets” serves as the hopeful closer of an album that otherwise explores several “dark stories” inspired by actual accounts of the working-class South.15 All three of the band’s songwriters get in the act: the speaker of Mike Cooley’s “Cartoon Gold” feels adrift, disconnected from family, while Shonna Tucker’s “Dancin’ Ricky” profiles a friend who’s struggling with self-control, and Hood offers stories of—among others—a cheating preacher who had his wife killed (“Go-Go Boots”), a Vietnam veteran experiencing flashbacks (“Ray’s Automatic Weapon”), and a man whose childhood trauma has left him an angry, abusive alcoholic (“Used to Be a Cop”).

Hood revises regional history by building on portions of that same history, which creates an inherent tension in “Mercy Buckets.” Michael Kreyling describes this historical friction as a key challenge for postmodern critiques of southern literature: “To put quotation marks around the real is not to efface the real; rather, it is to put it into a condition of multiple codes rather than the traditional realistic mimetic system of the one and only. History still exists; but we now acknowledge that we know it through a system of representations rather than in an unmediated, direct way.”16 In keeping with Kreyling’s “system of representations,” Hood gestures at the real etymology of “mercy buckets” but pretends it is commonly used figurative language. Hood calls attention to this act partly by playing with several metaphors, exemplified in the song’s fourth verse:

I will bring you buckets of mercy

And put a smile back on your pretty face

Bring a shovel if you want it

Carry your secrets to my grave.

In this verse, the most literal aspect—in Kreyling’s terms, “the real”—is that smile. But the verse also treats its final line as a literal act. Even though carrying a secret “to the grave” is a common metaphor, Hood undermines its metaphorical status with the preceding line: he seems prepared to actually bury those secrets, no matter whether they’re literal or metaphorical, whether they’re the subject’s secrets or the South’s. This verse, then, begins with a pretended metaphor and ends with a literalized metaphor, joining the two with an actual physical object and an offer of manual labor. Through this metaphorical play, which evokes the Southern Gothic as well as everyday language use, Hood’s story of the South makes space for mundane struggle. In this way, the song reimagines historical storytelling through its working-class subjects (which, in itself, departs from genteel traditions of southern historical and literary study).17

But known falsehood does not improve characters’ lives in any long-term sense, as they are mostly limited to mundane mercies. Studies of southern literature treat mercy as either the precursor to redemption or part of the process of coping with modern life.18 In Doreen Fowler’s words, mercy becomes possible after “taking ownership of what we would disown, our own corrupt natures and our death-bearing, brute existence in the world.”19 The songs and stories I examine here lay the groundwork for cultural healing through acknowledged lies, known falsehoods, and obvious untruths. They play with and undermine stereotypes of poor white southerners, and if they earn their mercies, it is through the processes of voicing and accounting for their positions. But taking ownership becomes more complicated when lies are involved—and while those lies may be merciful, they also reveal the limits of this kind of counterfactualism, especially when a hopeful rewriting of southern culture is put up against personal struggle, strained relationships, and other aspects of the white, working-class South.

3“I will bring you buckets of mercy”

These songs and stories share a preponderance of adversity, failure, and outright disaster. In response, they seek community. They share a working-class outlook embedded in stories of struggle. Tara McPherson contends that such plurality also gestures toward a more optimistic future: “A sense of hope materializes from these other narratives, a hope that, with hard work and some new skills, we can spin feeling southern differently, encouraging a kind of affective mobility that moves beyond nostalgia, guilt, and white racial melancholia toward forms of reparation.”20 Studies of the contemporary South often address texts’ reparative potential, suggesting they make possible a self-fashioning that hinges on the recognition of guilt, violence, or other cultural damage. By beginning with the metaphor of “mercy buckets,” Hood acknowledges the need to both give and receive mercy, then grounds the song’s version of the South in familiarity and compassion. In “Mercy Buckets,” Drive-By Truckers cultivate connection in multiple ways: the speaker offers a helping hand to the song’s direct addressee, and the song engages its audience lyrically through in-group access to a common linguistic joke and musically through a broad referentiality that exceeds the band’s alt-country and southern rock labels.

“Mercy Buckets” blends three familiar southern genres into what Rolling Stone calls “a raggedy revision of classic Southern soul.”21 Other reviewers note the overall “country-soul flavor”22 of Go-Go Boots and describe the album as “a mixed blast of Muscle Shoals balladry and the rattling country of the early-Seventies Rolling Stones.”23 This combination can be heard through Brad Morgan’s steady snare and John Neff’s slide guitar, which he often replaces with pedal steel when the band plays live. On the album version, Neff mostly muses over the drum line until a mid-song slide solo. At that point, lead guitarist Mike Cooley joins with his own solo, and the interplay between them and Hood’s rhythm guitar recalls the three-guitar attack of southern rock bands such as Lynyrd Skynyrd. Hood has said this is the band’s “prom song,” and the earnestness of his delivery makes that mirror ball fantasy feel possible—or at least, as middle-aged wish fulfillment, a nostalgic high point punctuated by loping, slow-dance-ready guitars.24

The history of country-soul, however, challenges such a nostalgic reading and should temper claims of sonic inclusiveness. According to historian Charles Hughes, starting in the 1960s, “racial ambivalence . . . lay at the heart of the country-soul triangle” of Memphis, Nashville, and Hood’s hometown of Muscle Shoals.25 Hood has written that his perspective on race relations in the mid-century South was shaped by his father, David Hood, the bass player for the famed Muscle Shoals rhythm section. According to Hood, his father’s “views on the Civil Rights era were shaped by the time he spent playing with Aretha and the Staple Singers. He looked at George Wallace and Bull Connor with great disdain, and was mortified to think that people around the world believed all Southerners were like that.”26 For David Hood, the story of the South as told through figures like Bull Connor doesn’t account for his experience at the Muscle Shoals Sound Studio.

For his son, writing decades later, even the combination of disdain and mortification seems too simple—and scholars like Jason Edward Black and Vernon Ray Harrison have argued that the band develops a persona that respects the past but pushes itself beyond the stereotypes of white southern men. 27Accordingly, Hood writes, “The South loves myths and legends, and while they may have roots in the truth, they often overlook certain complexities.”28 Whether the story being told shifts the ground under symbols of the Confederacy or sidesteps complicity with systemic racism, Hood suggests that the storytelling can’t live up to the actual story. While Hood’s lyrical reimagining of southern culture in “Mercy Buckets” performs exactly this kind of mythologizing—rooted in truth but not bound by it—the song’s structure indicates that such storytelling by itself is inadequate. After the fifth and final verse, which comes a little over halfway through the song’s 5:25 runtime, “Mercy Buckets” consists primarily of guitar solos, which help listeners access the ineffable in a way that the lyrics cannot. Perhaps even the final chorus, tucked between solos, might be read as beginning to depart from storytelling as its primary mode. Specifically, the mantra-like repetition of “I will be your saving grace,” the song’s final words, provides a thematic unity but, in terms of storytelling, broadens from the situational imaginings in the verses.

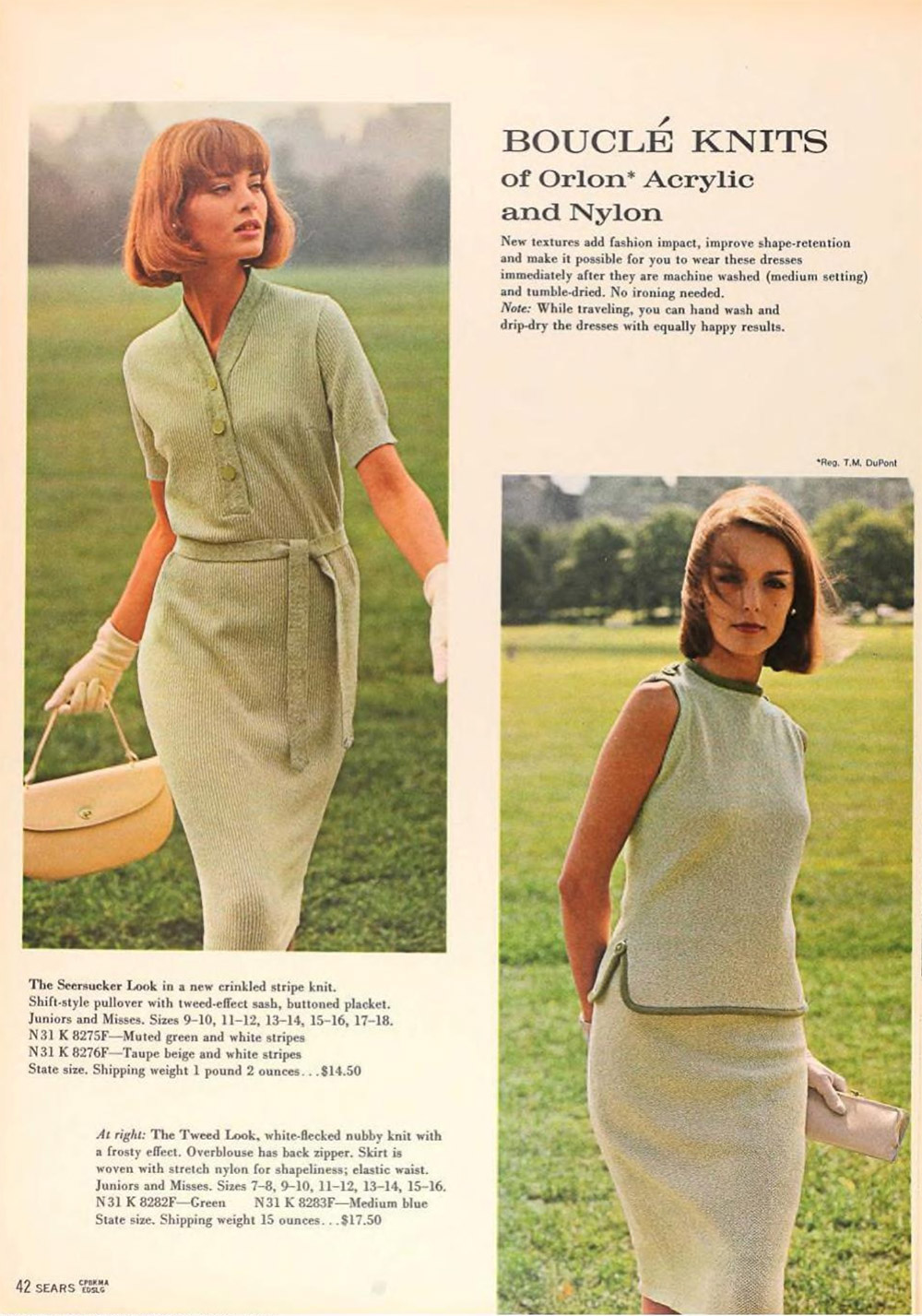

As a method for developing and sustaining emotional connection, storytelling also falls short—and conspicuously so—in Lewis Nordan’s “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game” (1986). Nordan represents the fracturing relationships of Sugar Mecklin and his parents, who live in the small town of Arrow Catcher in the Mississippi Delta. Events in the story take place over a long period of Sugar’s life, but its most dramatic moments occur in the moment Sugar’s mother slices her wrist in front of him and in the period just afterward, as she recovers from her injuries. The story gets its title from a family game, played mostly by Sugar and his mother, who remains nameless, in which they imagine backstories for catalog models. According to Sugar, “I loved and was terrified by the unpredictable drama and pain” in those sometimes-salacious stories.29 Robert Rudnicki argues that the game is a symptom of Sugar’s mother’s unhappiness, claiming that she “invents elaborate games and tells imaginative stories to Sugar in order to escape from the reality of her life.”30 Nordan rewards such a reading by showing the game’s negative outcomes: his father’s alienation and his mother’s attempted suicide.

Still, the story includes certain positive features of the game, not least that it facilitates a growing self-awareness in Sugar’s father, Gilbert. While Sugar’s mother is in the hospital, Sugar and Gilbert settle into a daily routine of work, hospital visits, and cubed steak: “It was a simple, manageable life. It required no imagination.”31 One night, anticipating her return, they decide to play the catalog game and, perhaps unsurprisingly, struggle. Sugar explains, “My father and I were incapable of inventing a world together. We were too much at peace in the one we already shared.”32 Gilbert has never understood the game, and this passage implies that he lacked the ability. But Sugar does not simply narrate Gilbert’s lack of imagination. In the first sentence, he emphasizes their mutual failing, which arises because they ignored the comfort that they had developed with each other. They begin lightheartedly, “two men in the fullness of [their] need and love,”33 and attempt to recreate the feelings and relationships of the storytelling game. After staring at the pages for a few embarrassed minutes, Sugar discovers that “it was not easy to do this without Mother.”34 Stories don’t come easily to them, and Gilbert especially struggles to create a fiction outside of his own experience. Eventually, looking at a model in the women’s clothing section, Gilbert says, “I think I’m beginning to see.”35 This epiphany appears to let him access the game, and Sugar thinks Gilbert is about to spin a story about the model’s fictional past, feelings, or relationships. Instead, Gilbert turns inward: “She sees me.”30

Gilbert does not tell a story that Sugar can share, demonstrating a clear difference between the playing styles of Sugar’s parents. When Gilbert starts to see, Sugar explains, “it was in this moment that my father’s imagination was born.”37 Nordan does not treat this as a praiseworthy accomplishment for hard work that paid off. Nor does he offer a story of the benefits to Mecklin family life. In the very next sentence, Nordan shows the profoundly unmerciful downside of Gilbert’s newfound abilities: “The rest of his days he spent in misery.”38 For both Gilbert and Sugar, Gilbert’s story was less magical than what Sugar’s mother was able to create—a difference seen in both how enchanting the stories were and how they affected the connection between parent and child. For instance, despite Gilbert and Sugar’s mutual desire for connection, storytelling weakens their relationship. Furthermore, Gilbert’s newfound ability makes him miserable, interrupting his previous comfort both with his son and within himself

Sugar’s mother, on the other hand, has no trouble using the storytelling game to relate to her son. But at one point, she exceeds the boundaries of the game. Rather than telling a clearly fictional story, she reimagines her own biography:

She told me the strangest story. It was exactly like a story she might make up about the Sears and Roebuck people, except that it was about herself; there was no catalog. She told me she was born in Saskatchewan. (Remember that not a word of this is true. She was born in Mississippi and had lived nowhere else in her life.) She said that her family had lived in a four-room fifth-floor walkup with cold Canadian winds whistling through the chinks in the thin walls.39

This moment is notable to Sugar because the game has been recontextualized. The turn to personal history evokes the way that “Mercy Buckets” uses historical revision to develop a personal connection. The difference is that Drive-By Truckers focus on broad cultural revision, while Sugar’s mother specifically alters her own biography. Sugar is conflicted in response: “I was torn between the wonderful melodrama of the story and the dangerous madness of it.”40 Part of Sugar’s attraction to the story is the way it transgresses his expectations for the game and their relationship. On one hand, she performs the detailed storytelling of the catalog game, which has been mutually consented upon and usually facilitates some kind of enjoyable intimacy. Indeed, Huey Guagliardo argues that Nordan’s short fiction emphasizes “the redemptive power of human connectedness.”41 In this instance, however, Sugar describes his mother’s personal turn as a “lapse into madness.”42 To Sugar, this story feels dangerous—not only does it display his mother’s unhappiness, but it indirectly portends her suicide attempt. As he says later, “the strength of imagination . . . had brought her to madness and near death.”43

In texts that create intimacies through known untruths—referring to Nordan, of course, but also these other songs and stories—lies often cover up something difficult or unpleasant. Such juxtapositions may make it easier for both audiences and characters to transmogrify those lies into truth, a way of consuming stories about the South that, according to Richard Gray, derives from a desire to “accept the counterfeit as if it were true currency.”44 For audiences as well as characters, acknowledged lies become part of the process of self-fashioning. But while lies can help create community or build relationships, these texts also reveal the limits of the lie as a method for personal connection. “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game”45 suggests that lies create only temporary intimacy. For example, just before Gilbert dies, many years after the story’s central events, he crawls deep under his house, and an adult Sugar must pull out his body with a rope. The sight of his father’s “jaundiced corpse” prompts Sugar to reflect on their failed attempt to play the catalog game. Looking at his father’s body, Sugar remembers being fearful while they tried to play the game and imagines what the catalog model must have seen in his father’s face: “an emptiness too vast ever to be filled up or given meaning. I looked away, in fear of what else I might see.”46 In the aftermath of that single attempt to capture the magic of a different relationship, Sugar sees an emptiness that relates not only to his father’s experience but also his mother’s. Storytelling here offers momentary intimacy but not long-term fulfillment, and while it may produce personal or communal intimacies, in these stories and songs it also reveals undercurrents of violence, trauma, and loss.

4The Limits of the Lie

Despite the pain that surfaces in these texts, country music and southern fiction often play the obvious untruth for a laugh. Canonical southern literature tends to dark humor, such as when, in Mississippian Eudora Welty’s “Why I Live at the P.O.” (1941), family theatrics erupt over a series of “deliberate, calculated falsehood[s],”47 (57), and in Flannery O’Connor’s “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” (1955), which features con man Tom T. Shiftlet gleefully casting doubt on several versions of his biography. The humor of country music forms these exaggerated lies into tall tales and “literalized metaphors,”48 such as when David Allan Coe’s “You Never Even Called Me by My Name” (1975) suddenly becomes “the perfect country and western song” through a morbid alchemy of country music tropes (not only does Coe fix the song’s supposed flaws by singing about mama, trains, trucks, prison, and getting drunk, the speaker’s mama “got runned over by a damned old train”).49 “Mercy Buckets” fits this pattern of tall-tale-styled exaggeration when Hood makes a metaphor from a malapropism. The joke’s relative commonness allows listeners to appreciate the song’s exaggerations and, perhaps, to recognize that Hood is creating an alternate history in which “mercy buckets” is not simply a joke but also a metaphor. So the song starts with a chuckle, then turns to the more serious business of imagining what “buckets of mercy” might actually mean.

Other texts are more skeptical of the reparative potential of these kinds of deliberate fictions. In Dorothy Allison’s “River of Names” (1988), the unnamed narrator tells her girlfriend, Jesse, several stereotypical stories of the unwashed, uneducated South, but she leaves out the beatings and rape, revealing them only to the story’s readers; in this story, lies are explicitly a coping mechanism. Unlike Sugar, who understands that his mother is not telling the truth about her past, Jesse doesn’t know the narrator’s story. Sometimes, the narrator provides partial narratives that obscure their most horrifying aspects. At other times, she simply lies about unpleasant memories, such as when she tells Jesse that her grandmother smelled “like lavender,” her “stomach churning of the memory of sour sweat and snuff.”50 The narrator resents Jesse’s much easier, middle-class childhood but also shelters her through humor and embellishment. After Jesse’s comment, “You tell the funniest stories,” the narrator responds, “Yeah. . . . but I lie.”51

Throughout the story, Allison’s narrator reveals to readers the sexual assaults, beatings, bullying, pills, and alcohol that she hides from Jesse, whose interest in funny stories about hillbillies leads the narrator to certain kinds of performance. At parties, she tells readers, while Jesse and her friends look at the narrator’s family photos, “I drink bourbon and make myself drawl, tell all those old funny stories.”52 Jesse and other partygoers lap up these stories in part because they are a familiar way to tell stories about the rural South. According to Allison Graham, “the American South, it seems, is frozen at its exoticized apex and nadir, relegated by tacit national consensus to a heaven-and-hell diptych of social types: sleepwalking belles and gentlemen of the Old South, and rampaging crackers and hillbillies of the Benighted South.”53 Standing in front of their friends, drunk and performing, the narrator becomes the boisterous hillbilly that partygoers expect. The narrator therefore plays to the stereotype within the story and recreates Graham’s diptych for readers. Jesse’s family becomes an updated version of the Old South, “her father going off each day to the university, her mother who made all her dresses, her grandmother who always smelled of dill bread and vanilla.”54 Though Jesse’s family are not in the rarified socioeconomic air of plantation society, the narrator’s impression of their upper-middle-class comfort seems like an unrealistic “fairy tale,” to be longed for but never achieved.55

Allison’s narrator’s public performances differ from the traumas she reveals to readers, which range from ironic humor to somberly recounted sexual assault. Thus, while the narrator tells funny stories to Jesse and her friends, she tells the reader another story, of specific accounts of sexual violence in her family: “It wasn’t funny for me in my mama’s bed with my stepfather, not for my cousin, Billie, in the attic with my uncle, for Danny with four strangers in a parking lot, or for Pammie who made the papers. Cora read it out loud: ‘Repeatedly by persons unknown.’ They stayed unknown since Pammie never spoke again.”56 Pammie’s rape silences her, an effect also seen when the narrator compresses these stories and turns to irony: “Almost always, we were raped, my cousins and I. That was some kind of joke, too.”57 Along with the comedy she performs for her friends, the narrator’s irony serves as a kind of misdirection, shielding both herself and the reader from the traumas of her upbringing. In “River of Names,” the narrator is besieged by her past, forced to perform her family’s story as anachronistic aberration even as she shows that Jesse’s “soft-chinned innocence” is rare among the women in her life.58

Yearning for Jesse’s innocence manifests as a desire to protect her, which suggests that the narrator’s lies about her past function as an act of mercy—for Jesse and herself. Jesse benefits from that mercy because she retains her innocence, and the narrator protects herself by suppressing the traumas of her childhood. This allows her to sustain the relationship a bit longer, even though she knows that “by not speaking I am condemning us.”59 Given the personal challenges that the narrator expects to face because of her continued lying about the past, perhaps this story’s version of mercy is a broader cultural one. In this sense, the narrator’s funny stories may constitute an act of mercy for her family, especially in those moments when Jesse and her friends are looking at the narrator’s family photos. as Katherine Henninger argues about several Allison stories, “pictures deprived of narrative tend to take on the dominant cultural narrative: in the case of pictured poor white bodies, family photographs may become social realist documentary, or perhaps even comic relief.”60 While Henninger focuses on the narrator’s family photos, there is a similar response to her stories. The narrator offers mercy for herself and her family by telling a story more like Beverly Hillbillies than Deliverance—still playing with poor white stereotypes, but more comedic than horrific. She thereby avoids “reproducing the stereotype that sexual abuse is what happens in poor southern families.”61 The narrator thus offers her friends and lover a comic revision of the South that is less personally painful than the actual story of her life.62

Covering up pain is also central to North Carolina-born Jason Michael Carroll’s song “Alyssa Lies” (2006), though the title character here attempts to cope with active, ongoing abuse. In the song, “Alyssa lies / to the teachers / as she tries to cover every bruise,” and her lies are transparent enough that the speaker’s “little girl” sees through them.63 The girl alerts her father to the abuse, but the next Monday at school they find out that Alyssa has been killed. Described as a “haunting expose of child abuse,”64 the song was popular on country radio. Listeners responded to Carroll’s lyrics about Alyssa hiding her mistreatment and then, after her death, the song’s “nightmarishly helpless quality” as the speaker relays the news to his daughter.65 He explains Alyssa’s absence in the final chorus, a variation on its first two iterations, telling his daughter that “she doesn’t lie / anymore . . . because there’s nothing anyone would do.” Carroll’s use of “would” instead of “could” suggests that, while listeners may feel helpless, the speaker, teachers, and other adults were not. In this sense, “Alyssa Lies” condenses Allison’s concerns from “River of Names,” raising the specter of what happens when people and institutions fail to protect southern children.

Alyssa’s suffering and the reaction to her death indicates how this song offers mercy for both its characters and audience. Tara Powell finds that “suffering is capable not just of teaching mercy and humanity but also of earning the same. Part of mercy is learning to recognize, regard, and respect the suffering of others.”66 While Powell is analyzing North Carolinian Reynolds Price’s novel The Promise of Rest (1995), her interest in the educational project of learning and earning mercy also relates to the video for “Alyssa Lies,” which is framed as a public service announcement to end child abuse.67 Director Kris Hixson opens the video with high school students writing journal entries in response to the song, noting how the song prompted students to report abuse. In this way, the video clarifies how audiences are expected to offer mercy: by recognizing abuse and showing compassion for victims. In the world of the song, Alyssa’s lies afford her the everyday mercy of privacy, and her friend has learned to recognize and report pain in others, which suggests that both may earn mercy. The adults, on the other hand, fail Alyssa, meaning that they neither offer mercy nor earn it.

Like “River of Names” and “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” “Alyssa Lies” bases its sense of mercy on the way individuals cope with tragedy. Through the correspondence of Southern Agrarian Allen Tate, Richard Gray describes southern writers’ attraction to scenes of trauma and misfortune as a recurrent theme of southern culture: “The imagination of disaster that Tate and [John Peale] Bishop shared in their correspondence and elsewhere—sometimes with a rather unseemly, lipsmacking relish—is surely one of the constants of Southern self-fashioning.”68 Certainly, the texts I study imagine disaster within these stories of personal loss, but as for “lipsmacking relish,” Drive-By Truckers’s winking Southern Gothic might fit, but not “Alyssa Lies.” Neither Carroll’s song nor Hixson’s video for it seem to relish the story of a little girl’s death, though it comes close in the song’s closing lines. After Alyssa has died, Carroll sings that she only attains mercy in the sense of Biblical redemption—“Alyssa lies with Jesus.”

Despite the pun, this version of the “deliberate, calculated falsehood” does not develop into a comedy, even a dark one. In this, it stands in contrast to both “River of Names” and “Mercy Buckets,” which develop their mercies through comic exaggeration. In both story and song, those exaggerations arise from what Gray calls a particularly southern “imagination of disaster.”69 Beginning with tragedy or loss, each of these texts depict how biographical or cultural rewriting can help characters cope with trauma and personal struggle. But they also portray the limits of the lie as a method for personal connection. “Alyssa Lies,” for example, points out one of the immediate and fatal limits of such an approach, while “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game” has the space to develop more nuance, suggesting that lies create only temporary intimacy. In each text, however, the lies also enable the speakers to provide everyday mercy to others—including the protection of Jesse’s innocence, the girl’s friendship with Alyssa, Sugar’s relationship to his parents, and Hood’s willingness to “hold your hand when you’re crossing the street.” In these stories and songs, the mercies derived from small kindnesses are a necessary component to life, history, and storytelling in the modern South.

5Habits of Mercy

In all of these texts, the audience clearly benefits from merciful lies, while the characters just as often suffer. In “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” Nordan submits Sugar Mecklin to repeated family trauma, partly because of how his parents reimagine their personal stories. In “Alyssa Lies,” not only does Alyssa die, but her classmates lose a friend. The video specifically clarifies how the audience benefits: while listeners of the song may feel sadness for the girls and, more generally, guilty about abuse that happens in their communities, the video suggests that they will benefit both themselves and their children by reporting the violence that they see or suspect. In “River of Names,” the audience similarly feels empathy for the narrator because of the abuse in her past, though they get the double benefit of also laughing at her made-up stories. In “Mercy Buckets,” Hood’s lyrics portray a long list of characters’ “hard times,” and its repetition of Southern Gothic tropes—such as hiding bodies, digging graves, and even paying bail—places the song firmly within a culture of violence. Still, he distances the listener from hardship through the metaphorical play of the phrase “mercy buckets,” thus conjuring a merciful South that he describes as a “counterpoint to the darker elements on the record.” 70

In the same interview, Hood emphasizes the transformative power of “Mercy Buckets” when placed among other songs on Go-Go Boots: “To have these different characters, some of them obviously being misguided and doing destructive or bad things, and then have this other thing in there that’s more positive—someone maybe finding the light. In all of those songs, the redemption comes through a kind of lasting love. It sounds trite and cliché to say love is the answer, but maybe it really is.”71 According to Hood, the songs on Go-Go Boots tell a story of overcoming hardship through “lasting love” but in the same breath notes that this is perhaps too simplistic. Still, “Mercy Buckets” offers the reparative possibility of reconstructing the contemporary South. The song’s prominent position as the album’s culminating experience, which Hood poses as a comparatively optimistic “counterpoint,” rewrites the South through a literalized metaphor advancing a culture of everyday generosity. Through that alternate history, Drive-By Truckers illustrate the potential of the merciful lie for both the liar and the listener.

Even so, these texts sidestep big-picture repair that would account for interconnected histories of white supremacy and racial violence. Their imagination of disaster is mainly personal—though sometimes broadly generalized—and does not necessarily extend mercy beyond family and friends. These authors and songwriters, however, do seem to be aware that their texts create only incomplete mercies. In “Mercy Buckets,” which offers an encouraging vision of a merciful South, the song’s closing guitar solos show where storytelling breaks down, and the link between Hood’s lyrics and cultures of violence insinuates that reimagining southern culture must be partly a reckoning with trauma. “Mercy Buckets” thereby joins many other southern cultural texts to show that mercy is not enough. In this article, the Mecklins’ stories do not ultimately repair damaged relationships, Alyssa’s lies only gain her temporary reprieve, and, although the narrator in “River of Names” provides certain types of mercy, the story remains unsettling in its ambiguities.

Within each of these texts, lies and untruths sometimes enable a more compassionate, inclusive southern culture, but the gains felt by their characters are often limited in both time and degree. According to Patricia Yaeger, this dichotomy structures a range of southern cultural texts: “southern characters can only find their identities in a site where the self is deeply, irremediably violated.”72 Yaeger argues that characters’ attempts to develop coherent identities requires them to account for the “habits of oppression” and “structural violence” of southern culture.73 This conception of southern self-fashioning extends to the merciful lie in that, even when those stories create mercy, they are simultaneously a kind of violence.

If coping with modern life must happen through untruth, mercy is perpetually diminished or delayed. The limits of mercy—as seen in the traumas both enacted and referred to—show that the readers and listeners are the primary beneficiaries of the merciful lie. With these texts, only the audience gets to feel good. Still, the songs and stories studied here attempt to “spin feeling southern differently”74 and, to some extent, they suggest how to move through and remember the modern South. Although they are intended for a range of audiences, each explores the interplay between mercy and truth (not to mention humor, intimacy, and tragedy) as a way to honor the traditions of southern culture, attempting to acknowledge its violences but not overdetermine the relationships and lives of the present. In this way, perhaps, the merciful lie is a method, a way of thinking that must necessarily fail its subjects but might yet benefit its readers. That only works, though, if they help their audiences replace “habits of oppression”75 with habits of mercy—in other words, if they act as a call to support and sustain communities through authenticity and compassion. “Mercy Buckets,” then, is not valuable in that it reimagines southern culture. It is valuable because it offers a way for the listeners of Drive-By Truckers to do so. Their compassionate acts may not be the same as Patterson Hood’s, but they may ask what “buckets of mercy” might mean in their own homes, their communities, and across the South.

Notes

- For the World War II origins of “mercy buckets,” see J. E. Lighter, Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang (New York: Random House, 1994). The joke lingers in foreign language classes today and, in that context, such mispronunciations reinforce stereotypes and consolidate group identities; see Connie C. Eble, Slang & Sociability: In-Group Language among College Students (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

- Drive-By Truckers, “Mercy Buckets,” Go-Go Boots (ATO, 2011).

- Scott Timberg, “All the Poets (Musicians on Writing): Patterson Hood,” Los Angeles Review of Books, February 2, 2018, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/poets-musicians-writing-patterson-hood/#.

- Scholars and critics widely describe Drive-By Truckers in terms of their relationship to southern writers such as William Faulkner, Harper Lee, Flannery O’Connor, and Larry Brown; see Kelly Dearmore, “Mr. Record Man: Drive-By Truckers,” Lone Star Music Magazine, March 1, 2014, http://lonestarmusicmagazine.com/mr-record-man-drive-by-truckers/.; Eric Mangol, “Reading Music: The Patterson Hood Interview,” Music Lit 101, April 1, 2014, http://musiclit101.com/2014/04/01/reading-music-the-patterson-hood-interview/.; Aarik Danielsen, “Drive-By Truckers Deliver Big Tales Worth Stopping For,” Columbia Tribune, April 29, 2010, http://www.columbiatribune.com/article/20100429/Lifestyle/304299680.; and Susina Jan Susina, “Alabama Bound: Reading Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird While Southern,” Southern Quarterly 54, no. 3/4 (Spring/Summer 2017).

- Drive-By Truckers, “The Three Great Alabama Icons,” Southern Rock Opera (Soul Dump, 2001). See also Angie Maxwell, “The Duality of the Southern Thing: A Snapshot of Southern Politics in the Twenty-First Century,” Southern Cultures 20, no. 4 (2014).

- Scott Romine, The Real South: Southern Narrative in the Age of Cultural Reproduction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008), 17.

- Patterson Hood, “The Art of Story Telling with Patterson Hood,” interview by Lori Mohr Brownstein, Louisville, February 8, 2012, https://archive.louisville.com/content/art-story-telling-patterson-hood-interview-music.

- Thadious M. Davis, Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, and Literature (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 7.

- In Hurston’s Mules and Men, the residents of Eatonville and Polk County, Florida, engage in good-natured, participatory storytelling, which they enthusiastically call “lies,” and which offer opportunities for voice and community-making among Black Floridians. See Adam Ewing, “Lying Up a Nation: Zora Neale Hurston and the Local Uses of Diaspora,” Callaloo 37, no. 1 (Winter 2014); and Cynthia Ward, “Truths, Lies, Mules and Men: Through the ‘Spy-glass of Anthropology’ and What Zora Saw There,” Western Journal of Black Studies 36, no. 4 (Winter 2012).

- See Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010); and Erich Nunn, Sounding the Color Line: Music and Race in the Southern Imagination (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015).

- Amanda Marie Martinez, “Redneck Chic: Race and the Country Music Industry in the 1970s,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 32, no. 2 (2020): 133.

- Travis D. Stimeling, “‘Stay Out the Way of the Southern Thing’: The Drive-By Truckers’ Southern Gothic Soundscape,” Popular Music & Society 36, no. 1 (2013): 19–29.

- Patterson Hood, “The South’s Heritage Is So Much More than a Flag,” New York Times Magazine, July 9, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/09/magazine/the-souths-heritage-is-so-much-more-than-a-flag.html?_r=0.

- See Buma, Michael. “‘Stand Tall, Turn Your Three Guitars Up Real Loud, and Do What You Do’: The Redneck Liberation Theology of the Drive-By Truckers,” Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 13 (2006): 1–29; and Chandler Harriss, “Whistlin’ Past Graveyards: The Drive-By Truckers and Southern Identity,” Popular Music & Society 42, no. 4 (2019): 419–437.

- Davis Inman, “Review of Go-Go Boots, by Drive-By Truckers,” American Songwriter, March 28, 2011, http://americansongwriter.com/2011/03/go-go-boots-the-drive-by-truckers/.

- Michael Kreyling, Inventing Southern Literature (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 155.

- Fred Hobson suggests that the strained relationship of the white working class to “southern” history indicates why the songs and stories featured in this article actively engage with and reimagine regional cultural history; see The Southern Writer in the Postmodern World (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991). Richard Gray argues that contemporary southern artists construct a modern, pluralistic South through processes of self-fashioning which require them to engage the region’s past, which suggests why each of them presents some variation on the stereotype of the southern poor white; see Southern Aberrations: Writers of the American South and the Problem of Regionalism (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

- See Jordan Rowan Fannin, “The ‘Strange Fruit’ of Flannery O’Connor: Damning Monuments in Southern Literature and Southern History,” Literature & Theology 35, no. 3 (2021); and Tara Powell, “Fiction of Mercy: Suffering Delight in Reynolds Price’s The Promise of Rest,” The Mississippi Quarterly 53, no. 2 (2000).

- Doreen Fowler, “Racial Scapegoating and White Redemption: Reconsidering Race in Flannery O’Connor,” Flannery O’Connor Review 17 (2019): 75.

- Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 6.

- Jody Rosen, “Review of Go-Go Boots, by Drive-By Truckers,” Rolling Stone, February 14, 2011, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/go-go-boots-112736/.

- John Staton, “The Drive-By Truckers Return to Town Wearing ‘Go-Go Boots,’” Star-News Online, April 13, 2011, http://www.starnewsonline.com/entertainment/20110413/the-drive-by-truckers-return-to-town-wearing-go-go-boots.

- David Fricke, “Drive-By Truckers Throw a Go-Go Party For ‘Go-Go Boots,’” Rolling Stone, February 17, 2011, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/drive-by-truckers-throw-a-go-go-party-for-go-go-boots-94068/.

- Chris Adams, “Drive-By Truckers: Patterson Hood Writes a Prom Song,” Wall Street Journal, February 10, 2011, https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-SEB-61582. Fittingly, Patterson Hood played an early version of Mercy Buckets at a wedding in 2009; see tykane8, “Patterson Hood Sings at Our Wedding!,” May 25, 2009, YouTube video, https://youtu.be/At8MHXTargw.

- Charles Hughes, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 8.

- Patterson Hood, “The South’s Heritage Is So Much More than a Flag,” July 9, 2015.

- Jason Edward Black and Vernon Ray Harrison, “Southern Paternal Generationalism and the Rhetoric of the Drive-By Truckers,” Western Journal of Communication 79, no. 3 (2015): 283–306.

- Patterson Hood, “The South’s Heritage Is So Much More than a Flag,” July 9, 2015.

- Lewis Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” in Sugar Among the Freaks: Selected Stories (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin, 1996), 15.

- Robert W. Rudnicki, “‘I Think I’m Beginning to See’: The Rustle of Lewis Nordan’s Fiction,” Southern Quarterly 41, no">3 (2003): 51.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 24.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 27.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 25.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 26.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 28.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 28.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 28.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 28.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 19.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 20.

- Huey Guagliardo, “‘A Life of Loneliness and Oddity’: Freaks, Alienation, and the Consoling Power of Narrative in Lewis Nordan’s Fiction,” Southern Quarterly 41, no. 3 (2003): 66. In contrast, Edward Dupuy argues that memory and narrative inform each other, which suggests why Sugar’s mother’s personal re-telling serves as an exception to arguments like Guagliardo’s; see “Memory, Death, the Delta, and St. Augustine: Autobiography in Lewis Nordan’s Music of the Swamp,” Southern Literary Journal 30, no. 2 (1998). Furthermore, Roberta Maguire groups “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game” with several early stories that show how Nordan represents the relationship between comedy and tragedy; see “From the Blues to Jazz: Lewis Nordan’s Fiction as ‘Equipment for Living,’” Southern Quarterly 41, no. 3 (Spring 2003).

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 20.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 25.

- Gray, Southern Aberrations, 360.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 25.

- Nordan, “The Sears and Roebuck Catalog Game,” 29.

- Eudora Welty, “Why I Live at the P.O.,” in Stories, Essays & Memoir (New York: Library of America, 1998), 57.

- Aaron Fox, Real Country: Music and Language in Working-Class Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 43.

- David Allan Coe, “You Never Even Called Me by My Name,” Once Upon a Rhyme (Columbia, 1975), MP3.

- Dorothy Allison, “River of Names,” in Trash (Ithaca: Firebrand, 1988), 13.

- Allison, “River of Names,” 21.

- Allison, “River of Names,” 14.

- Allison Graham, “The South in Popular Culture,” in A Companion to the Literature and Culture of the American South, ed. Richard J. Gray and Owen Robinson (Malden: Blackwell, 2004), 335.

- Allison, “River of Names,” 13.

- Allison, “River of Names,” 13.

- Allison, “River of Names,” 15.

- Allison, “River of Names,” 15.

- Allison, “River of Names,” 21.

- Allison, “River of Names,” 21.

- Katherine Henninger, “Claiming Access: Controlling Images in Dorothy Allison,” Arizona Quarterly 60, no. 3 (Autumn 2004): 102.

- Gillian Harkins, “Surviving the Family Romance? Southern Realism and the Labor of Incest,” Southern Literary Journal 40, no. 1 (Fall 2007): 120.

- In a 2015 interview, Allison commented that her writing has “a pace and a rhythm between grief and humor,” which she calls a “survival strategy”; see Mélanie Grué, “‘Great Writing Always Sings’: Dorothy Allison Speaks,” Southern Quarterly 53, no. 2 (Winter 2016): 135. Scholars explore similar dichotomies throughout Allison’s fiction. On the relationship between joy and shame, see Rachel Walerstein, “Recomposing the Self: Joyful Shame in Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina,” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 49, no. 4 (December 2016). For the felt shamefulness of white trash identity, see Bouson J. Brooks Bouson, “‘You Nothing but Trash’: White Trash Shame in Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina,” Southern Literary Journal 34, no. 1 (Fall 2001). For the ways storytelling helps cope in the aftermath of rape, see Laura S. Patterson, “Ellipsis, Ritual, and ‘Ritual Time’: Rethinking the Rape Complex in Southern Novels,” The Mississippi Quarterly 54, no. 1 (2000). On the penalties for truth-telling, see Kennedy Kathleen Kennedy, “Writing Trash: Truth and the Sexual Outlaw’s Reinvention of Lesbian Identity,” Feminist Theory 1, no. 2 (2000). Finally, see Peggy Dunn Bailey, “Female Gothic Fiction, Grotesque Realities, and Bastard Out of Carolina: Dorothy Allison Revises the Southern Gothic,” The Mississippi Quarterly 63, no. 1/2 (Winter 2010), which contextualizes Allison’s writing within Southern Gothic literary traditions.

- Jason Michael Carroll, “Alyssa Lies,” Waitin’ in the Country (Arista, 2007), MP3.

- Tom Mayer, “No Lies: Carroll’s Courtin’ Country,” Sun Journal (New Bern, NC), January 4, 2007.

- Brian Mansfield, “Carroll’s First Song Is Strong—Maybe Too Strong; ‘Alyssa Lies’ Breaks Out,” USA Today, January 18, 2007, D1. Regarding the song’s initial chart performance, see Wade Jessen, “Carroll Set Makes Big Splash,” Billboard, February 24, 2007. For broader public responses, see David Menconi, “‘Alyssa Lies’ Gives Steam to Jason Michael Carroll’s Rise,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC) (Raleigh, NC), February 2, 2007. Carroll’s hometown newspaper applauds the “resonance” of his “radio-friendly voice” but gives him only faint praise “for writing an effective country ballad”; see Jack Bernhardt, “Review of Waitin’ in the Country, by Jason Michael Carroll,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), February 2, 2007, WUP19.

- Powell, “Fiction of Mercy,” 259.

- Kris Hixson, “Alyssa Lies,” (I-40 Films, 2007), music video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VlE2J9Yj7U4.

- Richard Gray, “Writing Southern Cultures,” in A Companion to the Literature and Culture of the American South, ed. Richard J. Gray and Owen Robinson (Malden: Blackwell, 2004), 4.

- Gray, “Writing Southern Cultures,” 4.

- Adam Moore, “Interview: Drive-By Truckers’ Patterson Hood—Go-Go Boots,’” Premier Guitar, April 11, 2011, http://www.premierguitar.com/articles/Interview_Drive_By_Truckers_Patterson_Hood_Go_Go_Boots.

- Moore, “Interview.”

- Patricia Yaeger, Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women’s Writing, 1930–1990 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 182.

- Yaeger, Dirt and Desire, 182.

- McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie, 6.

- Yaeger, Dirt and Desire, 182.