1Introduction

In studying higher-education desegregation in the US, researchers often adopt the town-and-gown divide framework—a separation between the university or college and local communities. In the case of the University of Mississippi’s (UM) 1962 desegregation, many studies focus primarily on the realm of the university: James Meredith, the federal government and its troops, Governor Ross Barnett, and UM administrators, faculty, and students.1 Others concentrate on community figures like Duncan M. Gray Jr., who urged rioters (students, locals, and out-of-towners) to disperse and who used his platform in the pulpit to preach support for racial equality.2 These works offer important perspectives on the events surrounding 1962 and the people who influenced them. For the most part, however, they concentrate on the campus and the federal government as the loci for efforts to challenge UM’s White supremacy. When these histories incorporate local residents’ actions, the focus is primarily on segregationists who refuse the federal government’s orders to desegregate and a few outspoken liberal White outliers. What too often gets left out are interracial interactions in the Oxford-UM community and the influence of Black Oxford’s community-building in reshaping racial ideas on and off campus.

It is difficult to measure the direct impact—and sometimes even the existence—of daily personal interactions on individuals’ thoughts about race and desegregation. Rather than attempting to parse between change stemming from interpersonal relationships versus change as a result of federal intervention, I examine interracial and intraracial interactions across the town/gown divide in Oxford as spheres of influence. Black challenges to White supremacy at UM brought systemic racism into question even though those systems of oppression remained in place. Marilyn M. Thomas-Houston addressed a similar question by examining the lack of Black organizing in Oxford during and after the civil rights movement. She discovered a coalescence of factors, including geographical and infrastructural barriers, that worked against Black political organizing; an immobilizing and not unfounded fear of physical and financial White retribution; fractured communities that duplicated efforts instead of combining them; and a general consensus that Black Oxonians were better off than other communities throughout the state, which undermined motivations to organize locally. At the same time, Thomas-Houston concedes, there were individuals who confronted systemic racism on their own in the absence of mass organizing efforts.3

This work focuses on those individual actions and small waves of organizing in Black communities in and around Oxford. In small but significant ways, Black employees and visitors pushed the limits of Jim Crow beginning in the 1940s and later risked the extreme violence of White backlash by supporting James Meredith as UM’s first Black student while also maintaining their distance from him.4 Local Black communities continued to bolster Black students and their activism in small ways throughout the following decades, thereby demanding that White communities on and off campus start grappling with persistent systemic racism. Instead of fighting to fully integrate into White Oxford life, they invested in themselves and organized to sustain and thrive on their own, which was an act of resistance to White supremacy in its own right. In this way, they forced the historically White Chamber of Commerce to include them, alongside UM, in its pursuit of an economically vibrant Lafayette County.

One of the factors perpetuating the schism between university policies and town interactions is a lack of documentation. Interpersonal interactions can be difficult to track without artifacts like meeting notes, letters, diaries, audio recordings, or access to personal recollections because the generation of interest has passed away. Yet the UM Archives and Special Collections and the 1950 US Federal Census hold traces of everyday interactions cross-stitched between the university and local communities. UM’s collections from the 1940s to the 1970s contain primarily White faculty and staff papers, but they offer glimpses into Black life filtered through the White authors of memos, disciplinary reports, letters, and the like. Over the past few decades, the university has made a concerted effort to diversify these records, conducting oral histories with Black individuals about integration efforts in 1962 and from 1969 to 1970, and Black life in the area more generally, collecting Black Oxonian materials like the Soul Force newsletter, and archiving Black faculty and staff papers. There are traces of interracial interactions scattered throughout these collections despite the persistent archival gaps and silences about Black life. These interactions contain the possibility of challenges to racist beliefs on an interpersonal level, perhaps even influencing perspectives on UM’s desegregation and the long fight for integration.

It is also important to include a few notes on the intentional language in this essay. First is the distinction between desegregation and integration. Simply put, desegregation means eliminating established boundaries between groups of people. Integration means bringing groups together to form a new whole that incorporates both groups; it is not one group subsuming another. The presence of Black students, faculty, and staff at UM mean that it is desegregated—i.e., no longer Whites-only. Without reshaping its structures, policies, and practices to include and reflect all of its constituents, however, it is not integrated. This distinction recognizes Black student activism on campus post-1962 as part of rather than separate from the long struggle for integration. Second is the use of “UM” or “the university” instead of its well-known nickname as shorthand for the University of Mississippi except in direct quotations. The moniker “Ole Miss” originated in 1896 during a student contest for naming the yearbook, and it quickly became part of the university’s fabled “traditions.” As historian Charles Eagles points out, “Whites ironically employed the language of Black slaves, whom they considered their inferiors, to identify their beloved all-White institution. Based on the plantation mistress, the name ‘Ole Miss’ reinforced the university’s aristocratic image” and played into the gendered dynamics of racism in the South. With White women entering the student body in the 1880s, White men asserted their need to protect them and the feminized university from “assault” by Black men.5 This excuse was one of the primary arguments for supporting Jim Crow and justifying the lynching of Black men even though the reality was much more often White men assaulting Black women. In alignment with the University of Mississippi Sensitivity and Respect Committee’s 2013 report, I use “UM” instead.6 Third, I have chosen to capitalize both Black and White when referring to race.

2Black Employees on Campus

As many have emphasized before, segregation did not mean a complete separation between races or a total absence of Black people in Whites-only places. It was instead a strict regulation of how people acted and the ways in which people could occupy space. Jim Crow laws and customs dictated Black subservience to Whites while also requiring Black employees to be present in White spaces, frequently as maids or janitors, caretakers, cooks, chauffeurs, and more. Segregation attempted to dehumanize Black people in White spaces, turning them into anonymous laborers or erasable parts of the background with no families or communities. This system of White supremacy also instructed White people to ignore the Black individuals around them except when needed or unless they transgressed segregation rules.

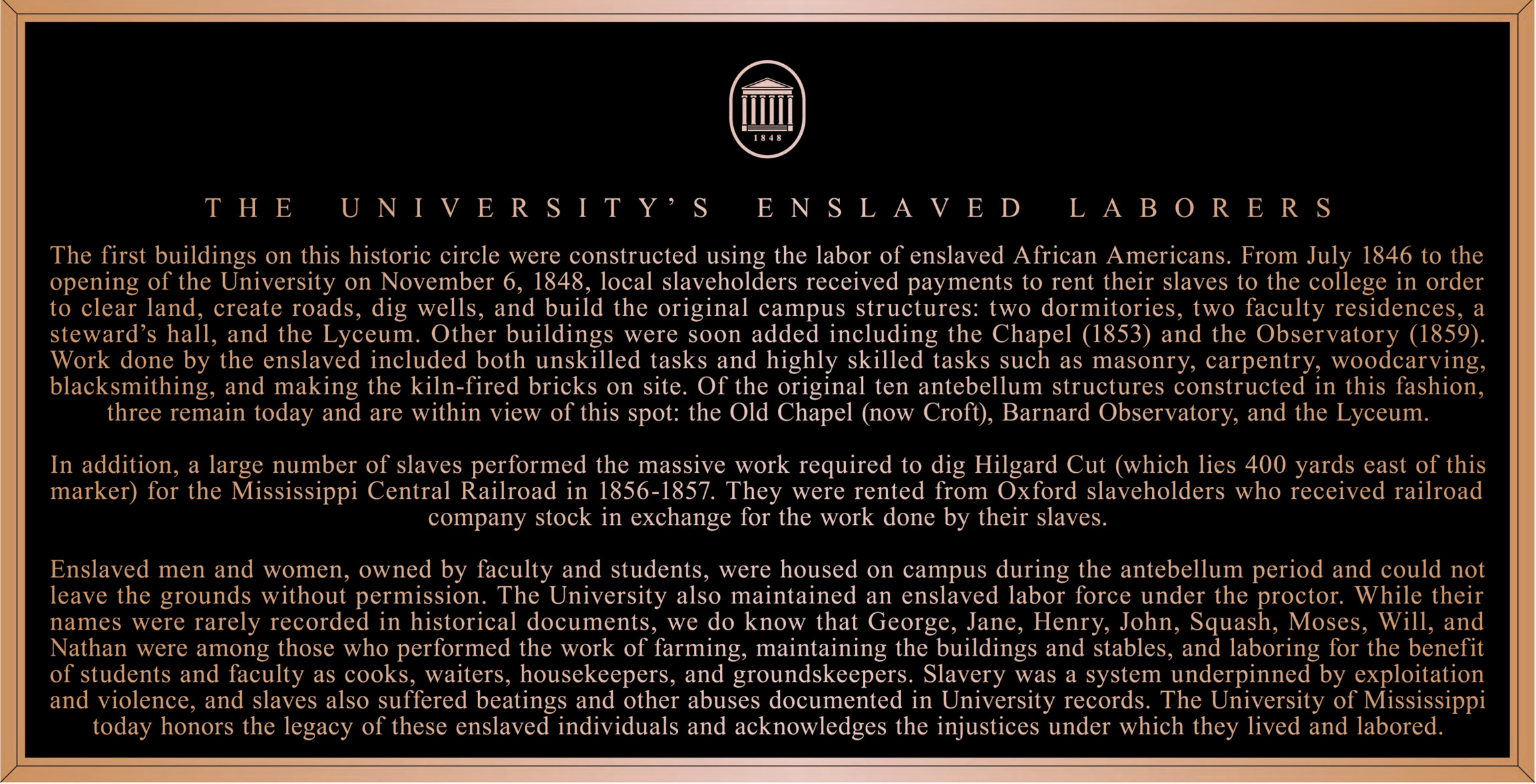

UM was no different. Before the US Civil War, university administrators, faculty, and students enslaved people and brought them to campus to build and maintain the physical infrastructure, cook meals, do laundry, and so on. One of UM’s recently added contextualization plaques explains that enslaved workers “were housed on campus during the antebellum period and could not leave the grounds without permission.”7 After Emancipation, Black employees continued to work for the university even though segregation barred them from becoming faculty, administrators, or students.

Interracial interactions were not always restricted to work, however. A 1948 UM disciplinary report described campus security disrupting gambling—an inherently social game—in a dorm room. Although UM’s Archives and Special Collections redacted the names of those involved, the report listed four individuals “and a Negro shoe shine named [redacted], also several students that we were not able to get their names.” The report’s author, campus watchman R. S. Black, further explained that “charges were made in JP Court [presumably Justice Court] against the above named, whereon they were convicted and fined $25.00.”8 There was no explanation of how the shoeshine man became part of this gambling group and there was no explicit mention of Jim Crow law violations, just that the watchman noted the shoeshine man’s race. The only offense listed was gambling and, according to Black, the court issued identical punishments to all the defendants regardless of race. Although not directed at repealing Jim Crow laws, this example shows that Black workers on or around campus had the opportunity to build interracial relationships that challenged systemic racism on an interpersonal level.

UM depended on Black employees for its operations, requiring Black people to be present on the Whites-only campus. Susie Marshall—a teacher and community elder in Freedmen Town, the historically Black neighborhood in Oxford—spoke in 2004 about the university as a place of employment for numerous Black community members. In her interview for UM’s Open Doors project, she recalled that the university “always had lots of new African Americans for jobs like in the cafeteria and different places. African Americans had a chance to get jobs at Ole Miss, more jobs were available during and after [desegregation].”9 Willie B. Tankersley was a UM cafeteria worker who later became the chancellor’s chauffer and house caretaker, working for the university for more than forty years. When he enlisted in the Army during World War II, Tankersley recalled the service coordinator offering him an exemption multiple times: “‘You’re a part of this university.’ He said, ‘We need you here and I want you to think this over.’ [. . .] And I said, ‘Well, I’m going to go’ and almost knocked him down.”10 Tankersley had become so vital to the segregated university that officials wanted to keep him out of war, but Tankersley refused and in the process pushed against White supremacy by making his own decision about his life.

Twenty years later, Tankersley had embedded himself in both the local Black community through his church, Boy Scouts, and a civics club and at UM as Chancellor J. D. Williams’s chauffer during Governor Ross Barnett’s defiance of federal orders to enroll James Meredith at UM. Tankersley described how the men who physically barred Meredith from stepping foot on campus ignored him “sitting on the steering wheel” whenever they talked with Williams as he drove by. As the tensions between Mississippi and the federal government escalated, Tankersley noted a declining recognition of and deference to the chancellor each time segregationists stopped and questioned them at the university gates: “They didn’t care what he was the chancellor of. They said what they wanted to say to him [and] finally let us come in to the chancellor’s home.”11 In addition to highlighting how UM and its chancellor became inconsequential in the battle over its desegregation, Tankersley’s memories demonstrate his access to the chancellor’s private conversations because White segregationists considered him to be more a part of the car than a person.

Depicting UM as Whites-only and devoid of Black individuals like Tankersley erases their centrality in the US, particularly in the South. It also negates their possible influences through daily interracial interactions and bystander access to White knowledge, conversations, and decisions. Tankersley defied that portrayal by placing himself in the middle of the action and in a similar position to the chancellor as the segregationists considered them almost equally insignificant as they drove through the university gates. Furthermore, as a growing community leader himself, Tankersley’s proximity to the chancellor’s conversations gave him access to information that could inform the ways in which he and other Black community leaders navigated the desegregation struggle and the ensuing heightened racial tensions in Oxford.12

Tankersley’s liminal position between the university and Oxford continued into his home life. He and his wife, Louise, lived on the edge of campus, half a mile away from the chancellor’s house.13 When Meredith enrolled at UM, Tankersley recounted his experience as a harrowing story of hunkering down at home while rioters and federal marshals swirled around them: “We had a little portable radio and so we sat by this little radio in our dining room and we just had it down real low, just enough so we could hear what was going on. [. . .] They didn’t know we were up in the room listening to all this. I don’t know what would have happened” had they known.14 He and Louise feared for their lives had any of the violent segregationists discovered that they were home. The Tankersleys literally and figuratively occupied a liminal space between the segregated university and neighboring Black communities.

Despite the danger of living near a White institution that some people violently tried to keep segregated, the Tankersleys persisted in reaching across the town and gown divide. Willie B. explained to UM in an oral history interview that in 1962 and 1963 he “had chancellors talk to [Meredith] in several occasions, and I was able to make arrangements for him to come and speak to people, Black people and white, too,” in church and other social activities.15 This kind of local support for Meredith’s direct challenge of White supremacy by desegregating UM was significant even though it did not shatter racial barriers. Meredith wrote in Three Years in Mississippi about Black friends who no longer associated with him for fear of White retaliation once he enrolled in classes at UM. In contrast, after registering for the Fall 1962 semester, Meredith described:

On my way out of the Lyceum Building, I encountered my first Negro. [. . .] He had his cleaning tools as all Negroes on the campus must keep them visible, and under one arm was tucked a broom. As I walked past, he acted as if he had not even noticed anything unusual on the campus, but just as I passed he touched me with the handle of his broom and caught my eye. I got the message. Every Negro on the campus was on my team. Every black eye would be watching over me at the University of Mississippi. Later on, I got to know this fellow very well. He told me that he just had to let me know that they were with me all the way, and to bump me with the broom handle was the best way he could think of to communicate with me.16

Local Black activism may not have been overt, but that did not mean that it was nonexistent. The racial oppression and constant threat of White violence—from firing employees to lynching—may have deterred highly visible organizing. It could not staunch smaller, more personal acts of resistance that supported integration efforts on campus.

The Tankersleys’ impact on UM and support of desegregation continued even after they moved away from campus and sold their house to the expanding university. In Willie B.’s recollection, the house later became the home of Phi Beta Sigma, Eta Beta Chapter, in the late 1980s.17 Phi Beta Sigma was the first Black fraternity to move onto UM’s historically White Fraternity Row after street construction forced them out of their house closer to downtown Oxford. They had acquired this new house—possibly Tankersley’s former house—from Delta Kappa Epsilon, but suspected arson destroyed it on August 4, 1988, before Phi Beta Sigma could move in, and UM helped secure them a new house on the same street within a couple months.18

In the twenty to thirty years that it took to reach such interracial support on campus, the everyday activism and influence through ordinary interactions became powerful acts of resistance when more overt Black political organizing was not possible. Marshall elaborated that “organizations were formed, like NAACP, but we weren’t allowed to have membership in NAACP. At that time, they would go around to church to see if anybody had any kind of sign that said NAACP—if we had organizations, you know. [. . .] It was about ten years later, [1972], when we were allowed to have membership in NAACP. [. . .] I think I have a record of who it was that was brave enough to get it started.”19 The NAACP Legal Defense Fund had helped Meredith gain admission to UM, so segregationists in and around Oxford patrolled Black community centers like churches for indications of organizing. They were afraid of organizations like the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee that were leading political, legal, and educational efforts across the South.20 Black communities had the potential to upset the White monopoly on political power in the state by advocating for and voting in their own self-interest. Historian Patricia Sullivan wrote that “by 1956, southern states had mounted an all-out war on the NAACP” in which they banned the organization from entire states, required that its chapters provide membership lists to state governments, and charged individuals or the NAACP with criminal penalties for filing lawsuits.21 Yet Black communities in and around Oxford continued to support and make their own challenges to White supremacy in mundane but consequential ways.

3Black Assertions of UM as Public Space

As a state-funded institution, UM was technically a public place, but in practice it was racially restrictive. Jim Crow laws regulated the space and the university’s policing of Black individuals on campus and turned it into a private space that only allowed Black people as laborers. In the mid-1900s, UM defined itself as an exclusively White space, but there were numerous Black people working on campus alongside their neighbors, friends, and family members. The ways in which Black employees extended community and family relationships onto campus pushed against White supremacy’s attempts to dehumanize them. The university’s need to police the space for Black people who were defying Jim Crow rules and norms also demonstrates how Black communities and individuals pushed back against segregation even if their immediate goal was not desegregation.

The 1950 US Federal Census reflected these divisions, indicating that everyone living on university grounds—students, administrators, faculty, and staff—was White, except for three students living in UM dorms listed as Chinese but born in Mississippi: Rosie Gang, William Fong, and Hin L. Wing. There were many more people, however, who worked at the university but commuted from off campus. The same census lists at least two hundred Black individuals whose place of employment was UM.22 For a student body of 3,582 in the spring of 1950, White students, staff, and faculty could overlook or ignore a couple hundred Black employees in service jobs.23

At the same time, Black staff were a constant presence on campus and were concentrated in areas with the potential for daily interactions with White people—primarily in the university’s laundry service, cafeteria, grill, and café; on the janitorial staff; and on groundskeeping or construction crews. A few were privately employed janitors, maids, or cooks for fraternities and sororities on campus, a couple people were maids or janitors at the university hospital or the University High School, and two sixteen-year-old boys—Frank P. Campbell Jr. and Alonzo C. Stokes—worked part-time at the university golf course.24 Although they were at UM as laborers, the high proportion of Black employees in these departments facilitated community building and a claiming of campus spaces as their own.

The laundry and housekeeping were divided by gender among Black employees. University Laundry hired mostly women, assigning each one a single task, such as pressing, ironing, or folding. There were also a few specializations: Virginia McEwen operated the flat work machine, Sallie B. Buford and Naomi S. Fleming checked the completed laundry before it went out for delivery, Alberta P. Booker did dry cleaning, and Roberta L. Price was a seamstress. One of the few men working for University Laundry was Thomas Morgan, who pressed wool garments. The census was conducted in April, and the laundry workers reported having worked from eleven to fifty-four hours the week before they were surveyed, with the majority working forty to forty-eight hours. Similarly, only women were maids, like Hixie Casey who was the housemaid for the chancellor’s home, and only men were janitors. Maids reported working fifteen to seventy-two hours the previous week, with the majority logging thirty-five to forty-five hours. Janitors reported working twenty-seven to ninety-six hours the previous week, with most men tallying forty to forty-eight hours on the job.25 Although the census documented men and women working similar numbers of hours, it did not account for the additional domestic labors of cooking, cleaning, and dependent-care often expected of women before leaving for their shifts at the university and upon returning home from them.

Cafeteria, grill, and café jobs had more gender parity, but, overall, they employed more Black men than Black women. Men were typically cooks, bakers, butchers, meat slicers, delivery people, storeroom operators, waiters, and dishwashers. Women were most often cooks, line servers—a few specifically designated themselves as salad makers, vegetable preparers, or pie handlers—and waitresses, while others did pantry work, cleared tables, and washed dishes. The census reported a few people as holding more supervisory positions too. Willie J. Booker had the title of head butcher, Joe M. Buford and W. Hamp Davidson were head/chief cooks, and Eugena King was a saleswoman in the cafeteria store. Everyone worked similar hours to those in laundry and sanitation services.26

With some exceptions, the majority of Black employee positions at UM mirrored those in other White businesses and private homes: cooking, cleaning, and maintenance. Extending the segregation status quo to university life meant that, by design, interracial interactions on campus replicated those off campus. The idea was to maintain rather than disrupt Jim Crow social norms. Yet there were still several hundred Black employees on campus, many of whom lived near UM and/or had relatives who worked for and knew the families of White students, faculty, and staff. The university’s Black workforce and White populations were therefore not wholly unfamiliar to each other despite the racial stratification. Furthermore, the university was an opportunity for students to explore new ways of being and to test the limits of social interactions. More liberal professors and White staff may have introduced students to and engaged their colleagues in discussions that questioned segregation. James Silver is well known for opposing segregation from the time he joined UM’s History Department in 1936 until his departure in 1964 as a result of harassment and efforts to fire him following his public befriending of Meredith and scathing critique of how UM handled its desegregation.27 Silver was open about his support of Black Mississippians before the 1960s. When Clennon King tried to apply to UM for graduate school in 1958, Silver’s colleagues recalled their previous conversations. They mused that “this is what Silver [illegible] had wanted, but [they doubt] if he would want this man who is a segregationalist [sic].”28 Students, staff, and faculty could interact and form bonds with a range of people at UM, including (potentially) its Black employees.

The familial bonds and community ties between Black employees at UM similarly challenged White supremacy’s goal of dehumanizing Black people. The university frequently employed spouses, like the previously mentioned Bookers who were head butcher and a dry cleaner or William and Mary Burt who both worked in the cafeteria, William as a dishwasher and Mary as a “line girl.” Parents and children, aunts or uncles and their nieces or nephews, and cousins also secured simultaneous employment on campus. Myrtle Porter, a divorced mother caring for her two sons, was a housemaid for a sorority, while her son Shirley Porter Jr. was a janitor in the library. Joe Mitchell and his son were both janitors for fraternity houses, and chief cook Davidson had the help of his nephew, Eddie L. Shannon, in the cafeteria kitchen. In addition, Black UM employees sometimes housed their coworkers or helped find jobs at the university for lodgers under their roofs. Elbert J. Morgan was a University Laundry washer who leased a room to Clarence and Marjorie Blue, and Marjorie folded laundry alongside Morgan. Widow Annie R. Carolhan prepared vegetables in the cafeteria and all three of the lodgers in her house worked with her. Head cook Buford also provided housing for ten lodgers, seven of whom had jobs in the cafeteria, laundry, or sanitation. These relationships presented a community of Black employees supporting each other through segregation.29 They sought out and helped each other obtain university jobs to escape the sharecropping that was prevalent in more rural parts of Lafayette County. In the process, they created greater economic mobility and stability as individuals and as a collective, and they carved out space on campus for themselves and their communities.

Reports of disciplinary investigations on campus offer a glimpse into the porousness of the campus/town delineation in the 1960s. Because university officials made these reports during Jim Crow and the height of the civil rights movement, these documents frequently present the existence of Black individuals in White spaces without White permission as criminal. Campus police severely regulated Black access to White spaces out of fear of individuals transgressing segregation norms and the potential for antiracist demonstrations. In October 1964, UM Chief Burnes Tatum reported that eight unnamed Black “boys between the ages of 16 and 18 years of age were turned away” from the UM football game because they were neither university students nor employees. Recently retired from the university, Hamp Davis also tried to attend the game, but security denied him entrance without a ticket, and the ticket office refused to sell him one. Tatum recounted Davis’s observation that “he had not missed a football game played on the campus for forty years.”30 Even though UM excluded Black community members unless they worked for or attended the university, these attempts to attend the football game suggest that some local Black residents saw it as part of their lives outside of their employment. When White Oxford was absorbed in UM home football games, local Black communities also felt their presence. Some Black individuals saw university events and campus spaces as part of their community life—albeit in a limited capacity—not separate from it. Whether intended or ancillary, this pushback to UM’s racist policies framed football games as community spaces and activities to which Black residents should have equal access as citizens, not just as students or employees.

Other reports documented campus police surveillance of Black individuals at UM who they could not identify or who visited in more mundane contexts. UM security trailed a Black man in December 1964 who sat alone in an empty section of the football stadium for part of a game and then mingled with White men in the Alumni House before leaving by bus. Chief Tatum also responded to a call reporting the presence of Black men in the cafeteria, whom he assumed were guests of the White faculty they sat with and thus he never approached them. In January 1965 campus security investigated complaints of a White male student, later identified as a member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, trying to bribe custodial staff for a key to the physical plant. He had enlisted Guy Porter, a Black janitor working at the fraternity house, in his scheme. Chief Tatum referred the student to the Dean of the Division of Student Personnel and recommended that “Porter be barred from the campus and not be allowed to come back.”31

That same year, there was a summary of campus security repeatedly instructing a Black Oxford high school student to leave campus and, in the report’s language, stop “bothering” UM’s Black students.32 These examples are from a small collection of disciplinary records among Dr. Franklin E. Moak’s papers, Dean of the Division of Student Personnel between 1964 and 1981, and suggest that there were more interactions like this on campus than these few that remain in the archive. They detail the policing of Black bodies and behavior by both campus security and by Whites on campus who reported the presence of Black individuals for investigation. They also indicate a more flexible town/gown divide. Black people were present on campus as visitors and townspeople, not just as employees at work or later as enrolled students. Even though some White staff alerted campus police to their whereabouts, Black visitors’ presence and reimagining of prescribed roles when in these traditionally White spaces was everyday activism—or micro-activism—challenging White supremacist social norms.

4Local Black Organizing

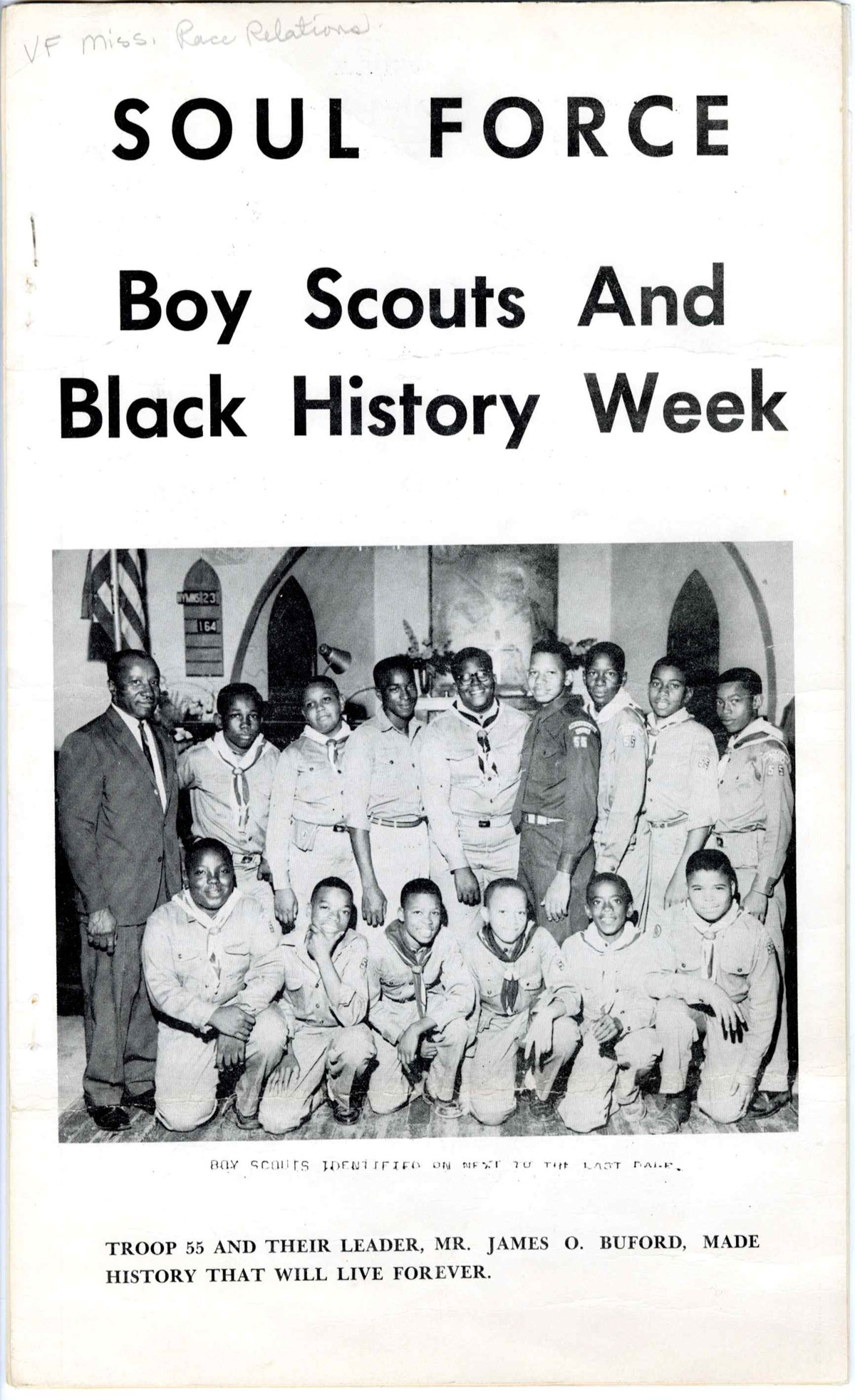

Even though White supremacist intimidation suppressed NAACP membership in the Oxford area until the 1970s, it could not prevent local Black communities from their own grassroots organizing. Freedmen Town residents and Black families in the area had been pooling their resources, establishing their own organizations, and investing in themselves for decades under Jim Crow. In addition to their own churches, schools, and social and civic clubs, they established Boy Scout Troop 55 in 1941 with a Cub Scouts group fifteen years later, and the Oxford Community Chorus sometime around 1947.33 Individuals like Tankersley—Boy Scout Committeeman and member of the Men’s Civics Club—and Della Davidson—Soul Force contributing editor, Cub Scouts Den Mother Committeeperson, director of the Oxford Community Chorus, and assistant principal of Oxford Elementary School—appeared repeatedly in the Black newsletter magazine Soul Force as participants and leaders in these efforts.34

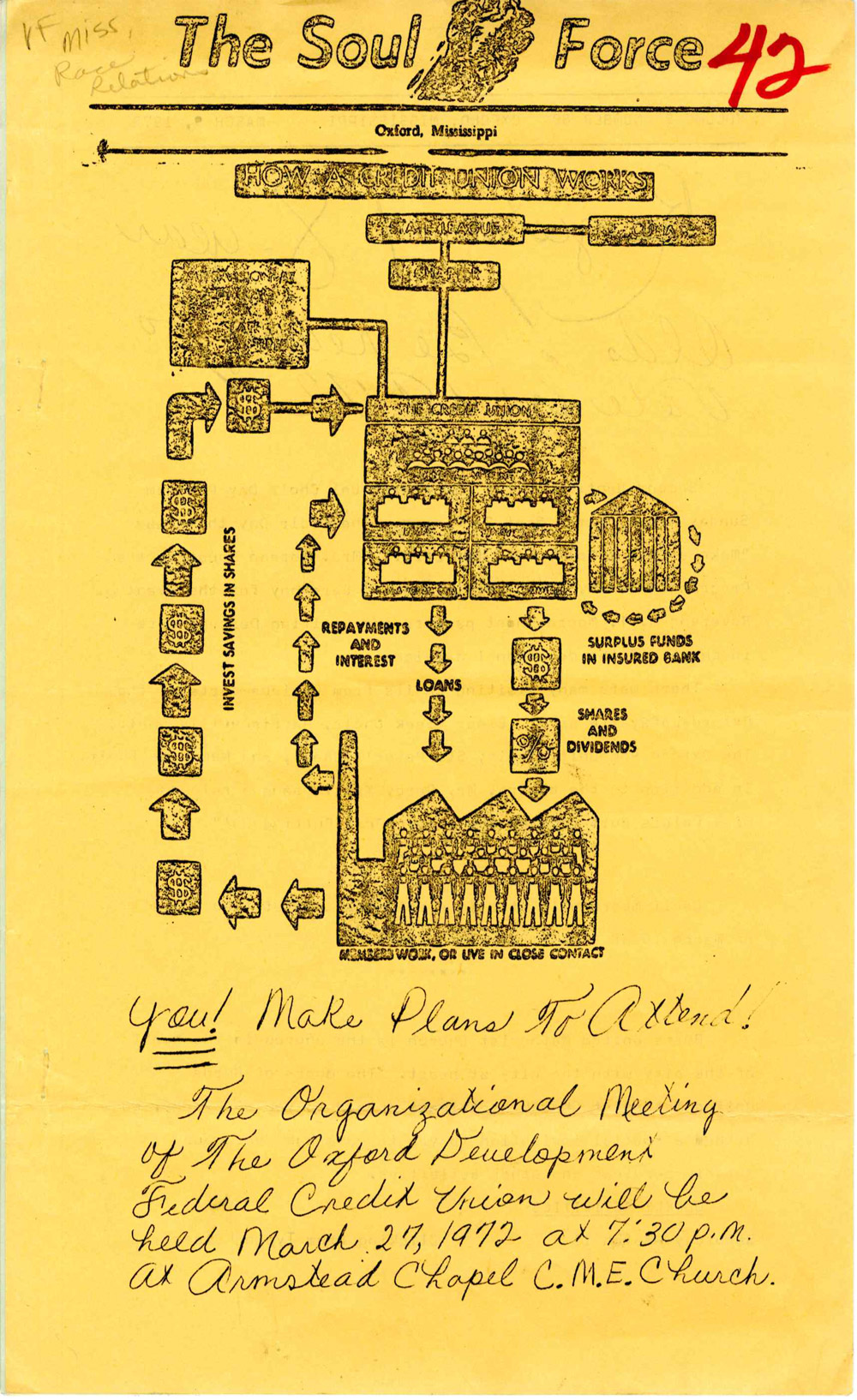

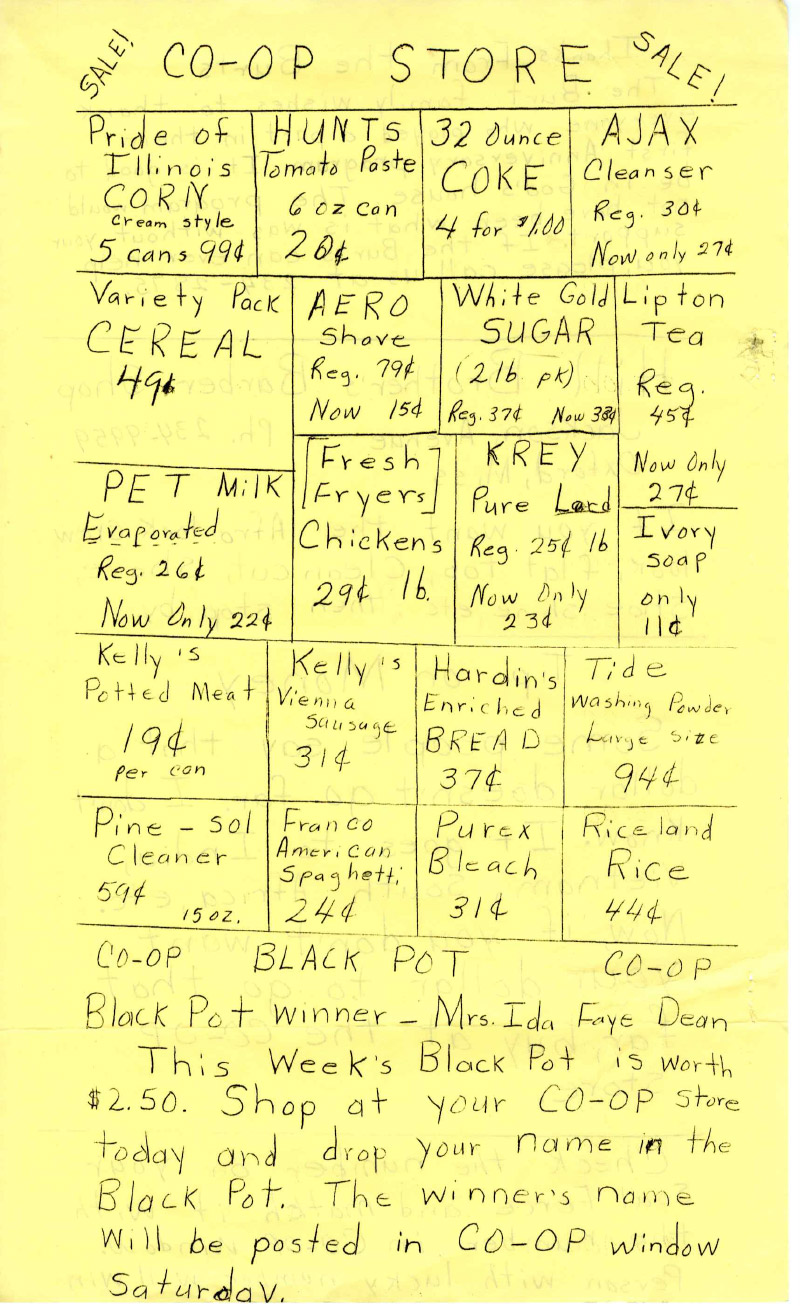

The federal government’s further enforcement of desegregation in the late 1960s and early 1970s also dampened White suppression of Black political engagement. Across Mississippi, Black families supported by civil rights organizations like the NAACP and Legal Defense Fund brought increasing numbers of lawsuits against still-segregated county public school systems. These efforts and the court rulings in their favor signaled the state’s inability to legally delay school desegregation any further. It also demonstrated the diminishing effectiveness of White intimidation to maintain Jim Crow, which segregationists began replacing with campaigns to establish Whites-only private school systems.35 Lafayette County and Oxford public schools quietly desegregated over the winter break between 1969 and 1970. As fears of violent White retaliation eased, Black communities in the Oxford area began joining the NAACP and expanding their local organizations by establishing the Oxford Development Association and its Soul Force publication, the Oxford Development Federal Credit Union, and a co-op store.36 The primary purpose of these establishments was to serve Black community members excluded from or exploited by White opportunities, economies, and systems, but their impact was much wider.

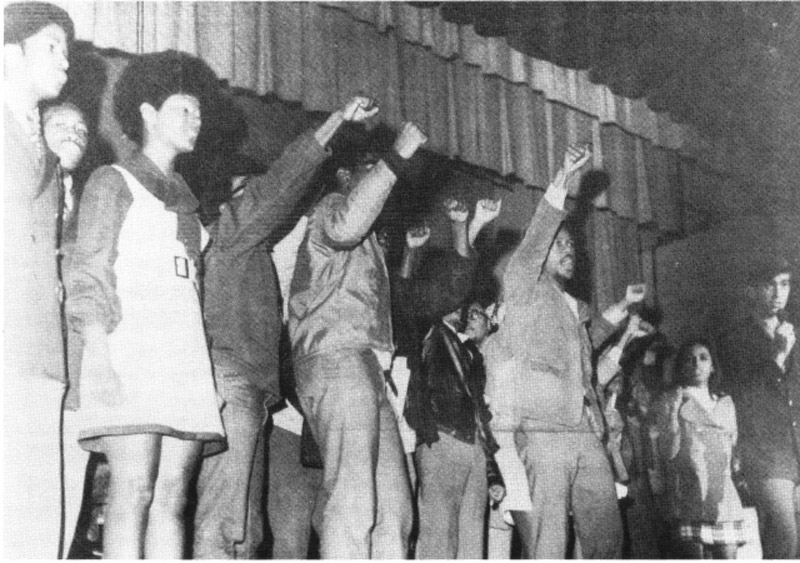

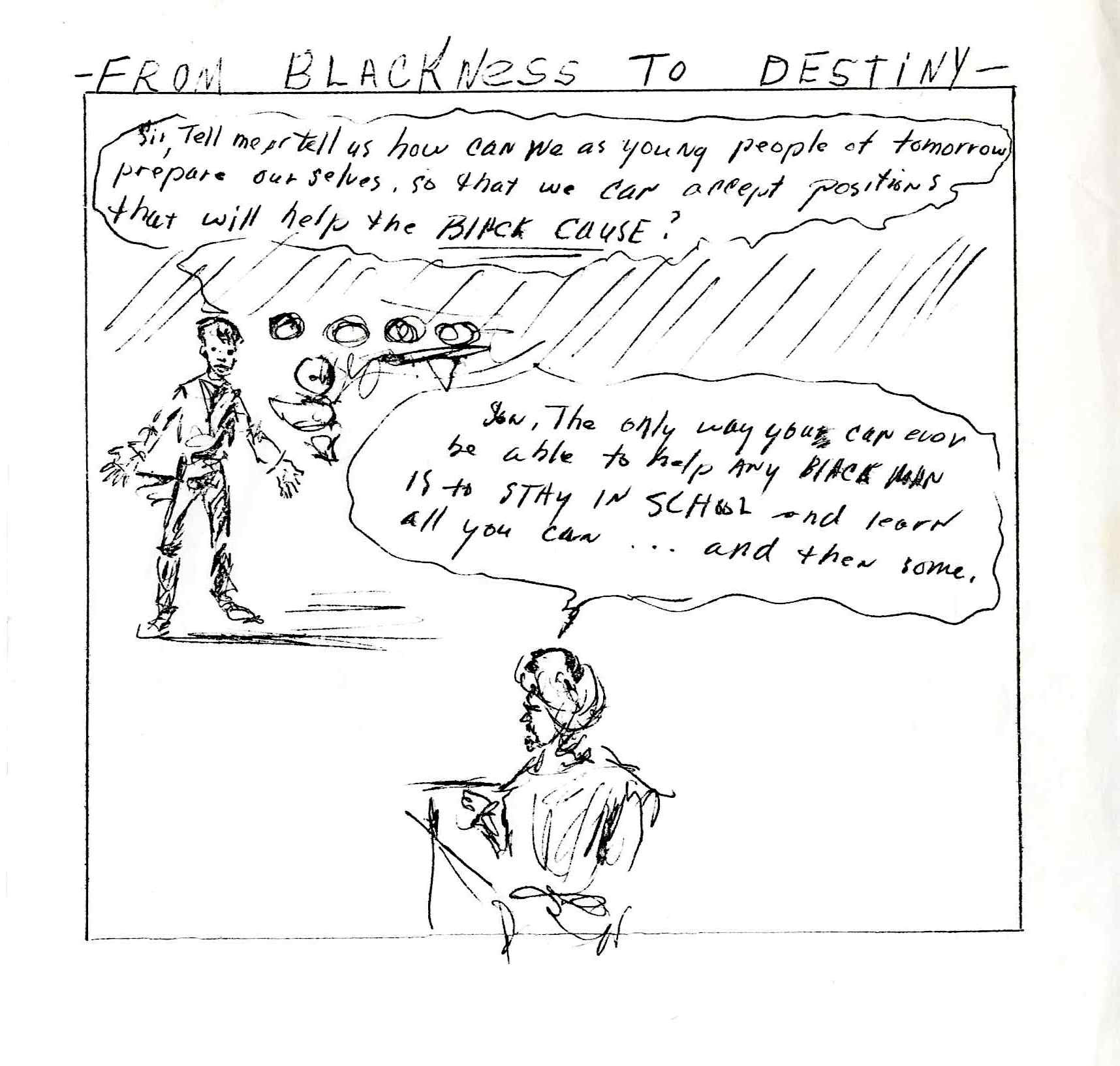

Black community building around Oxford put pressure on local White communities and historically White institutions, including UM. In 1970 Soul Force publicized the UM Black Student Union’s upcoming dance at the National Guard Armory: “Music will be furnished by the Ebony Soul, a local Soul group. [. . .] Everyone invited! Please come!”37 Two years later, the newsletter reported on the success of a beauty and talent show that “the Black Student Union and Co-Op Store sponsored.”38 This public support contrasted with Meredith’s experience of being almost shunned by Black people around Oxford less than a decade before, but it is also reminiscent of the Black community-building that stretched over the campus/county divide. In the 1970s, Black communities around UM and Oxford publicly supported and galvanized around the Black youth on campus, some of whom were their own children. Linnie Liggins was born and raised in Oxford; her mother worked as a sorority house cook for a while, her grandmother worked for a UM professor’s family, and archival documents suggest that one of her relatives was part of the Boy Scout Troop 55 group picture that appeared in the February 1972 Soul Force celebration of the troop. At her grandmother’s insistence, Liggins transferred from Tougaloo College to UM in 1967, but felt isolated on campus as one of only a relatively few Black students. She joined the Black Student Union (BSU) with the strong conviction “that through the Black Student Union . . . we might be able to achieve some of the goals that we were striving for, and that was more inclusion here at the university.”49

Liggins was part of the BSU group protesting for full integration—including UM hiring Black professors and establishing a Black Studies Program—during an Up with People concert on campus in February 1970. The highway patrol responded by arresting them and more than eighty other Black individuals in attendance, at gunpoint. By word of mouth, her grandmother heard that Liggins was part of a group of Black students arrested and sent to the Lafayette County Jail. When her grandmother arrived and spoke with her, Liggins “told her that maybe she could get some other family members or some other people in the community to help bail us out. [ . . .] So that we could all come out together. We didn’t want to leave anybody there alone, and I was the only person who actually lived here in town.” Her grandmother did just that, and the community bailed them out within a few hours.40 Liggins’s experience underscores the importance of Black Oxonians in supporting Black UM students’ struggles to be heard on campus. By throwing its weight behind the students, many if not most of whom they did not personally know, the Black community sent its own statement to UM and Oxford’s White communities that these students were not just “acting out” but were instead part of a larger fight against racial injustice.

Liggins was not the only one. Transferring to UM a few years later, Oakland, Mississippi, native Thomas Brown described a similar experience. He explained that in the early 1970s, “everything about Ole Miss suggested this is not the place for you.” He remembered two Black athletes and no Black professors, “so I spent a lot of my time at Ole Miss working in the community.” Since he could not find or establish his community on campus even with the BSU, Brown turned to community off campus. He built a relationship with his pastor and mentor, Wayne Johnson, who had established the Oxford Development Agency, Soul Force, and the co-op store. Working in the Black Oxford community with Johnson meant that Brown “was out doing community stuff, which helped my sanity as a student. . . . Ole Miss was just not a place where I spent a lot of time other than class.” Black communities in and around Oxford became a home and support system for Black students like Brown. By welcoming and supporting students, Black communities were also furthering efforts to keep UM desegregated and to push it toward integration.41

The 1970 demonstration and subsequent arrests made waves in the White communities on and off campus. Long-time history professor C. L. Marquette kept daily journals for a large portion of his life, including the 1970s. He noted conversations the next morning on campus, including rumors that “Carroll, the Methodist Minister, and the Minister from St. Andrew’s Meth Church bailed out some or all of the blacks arrested the other night. Mrs. W. was hot under the collar of that.” The next day, he described how a fellow history professor Dale Abadie

said the granddaughter of the Negro Maid they employ was caught in the [illegible] and ultimately carted off to Parchman without an opportunity to tell the grandmother. I do not know if she was an activist or not. Abadie said he would have bailed the girl out “if I had the $50 cash.” I told him I would not bail out any person, I think especially if the person was one of the protestors who took possession of the stage that eve.

They were most likely referring to Liggins but had misinformation about her being part of the overflow from the local jail that the highway patrol took to Parchman Penitentiary. Nevertheless, Marquette’s journals demonstrate how there was not a hard delineation between the university and the town; how the protest and arrests on campus made ripple effects throughout campus and into the White Oxford neighborhoods. Abadie’s personal connection to Liggins’s grandmother meant that Liggins’s arrest had even more of an impact. Marquette and a colleague had previously dismissed the Black student protest in UM’s cafeteria the day before the Up with People concert as the actions of students from out of town. His journal entry captured how his colleague “surmised they all couldn’t be ‘our own blacks’ so he concluded some came over from Miss Valley College at Itta Bena.” In contrast, Liggins being native to Oxford—and her Black Oxford community rallying behind her and her classmates—forced local Whites on and off campus to start grappling with both the White supremacist issues that students were protesting and how the university, town, and state responded to the protests.42

Local Black communities also used financial donations as a way to position themselves as UM stakeholders. In late 1970 or early 1971, around the same time that the university expelled eight of the Black student protestors, the Lafayette County Civic Club made a donation to one of UM’s scholarship funds. Tankersley represented the Club, and then-chancellor Porter L. Fortune Jr., with whom Tankersley worked daily, wrote him and the Club a thank-you letter. Fortune highlighted that the donation was “for the benefit of the scholarship fund of the University which bears the name of your Club.”43 Although it was unclear whether or not this scholarship supported a specific group of students, such as Black students and/or civically engaged students, Tankersley and the Club used the financial donation opportunity to make their presence known and to stake a claim in the university’s development.

Black investment in their own communities similarly pushed White Oxford to value Black businesses. Some of the establishments that Soul Force encouraged its readers to patronize and support included the co-op, the credit union, the day care center, Hill Brother’s Barber Shop, and multiple discount furniture stores. Its June 21, 1973, issue further urged readers to establish “drug stores, shopping centers, banks, hardware stores, dry good stores, dime and dollar stores.”44 Even the historically White Oxford-Lafayette County Chamber of Commerce took notice. At their February 1972 meeting, the Chamber of Commerce devoted a section to local Black businesses. It tallied “twenty businesses owned or operated by our own black citizens. There are probably more.” Going even further, the Chamber stated that it “offers all of its facilities to these businesses and will help them in every possible way.”45 There is due skepticism about the phrase “every possible way” considering that the general segregationist approach to “all deliberate speed” for complying with the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education desegregation orders meant decades of stalling. However, it is notable that the Chamber of Commerce adopted the stance—at least in their rhetoric—that Black businesses were integral to the entire county, not just to Black communities.

Additionally, the Oxford-Lafayette County Chamber of Commerce included UM in its purview. The board members included local business leaders—many of whom were UM alumni—like First National Bank President Garner Hickman, clothing boutique founder and owner Howard Duvall Jr., physician Lloyd Gerald Hopkins, Oxford High School Superintendent Gene Meadows, and Oxford Production Credit Association Vice President Lester Young, as well as UM administrators and faculty members Frank Moak and Robert Khayat. Listed in the February 1972 monthly meeting agenda was a notice that anyone could purchase a UM student directory from the university.46 This announcement and the public availability of the student directory raises questions about how individuals—particularly those in the White Citizens’ Council and the Ku Klux Klan—may have used the directory as a surveillance tool to keep watch over the growing number of Black students on campus and potential interracial relationships or roommate assignments. Seven years before, students notified UM administrators of two publicly visible, interracial, student couples of Black men and White women, purportedly out of fear for the couples’ safety. The women’s parents received anonymous phone calls with death threats, reports of bounties being offered for murdering the female students, and offers of extortion in exchange for sparing their daughters’ lives. The women also received threatening anonymous calls to their dorm rooms. These archival collections contain no documentation of the Black men’s experiences during this time or the intimidation their families received.47

A publicly available student directory from the same time indicates the persistence of the notion that this state institution was in fact an extension of the town. The directory was an opportunity for those outside of UM to see which local youth were attending the school and how many out-of-town students were there. Of all the counties in northern Mississippi, UM’s own Lafayette County had at least seven times as many students enrolled in the university that year than most.48 Along those same lines, the Chamber of Commerce’s “Program of Work: 1973–1974” pamphlet included a page on the “Community Relations Division.” It listed this Division’s mission to “promote better relations among all citizens of our community, including: Oxford, Lafayette County, University, Students.”49 Furthermore, UM’s Executive Vice Chancellor in 1974, Jerry C. McCall, suggested creating a recruiting committee for the university composed of “town leaders . . . [who] could also take a list of candidates in the neighboring counties and call on them.”50 Both the university and the Chamber of Commerce recognized the interdependent nature of UM and Oxford. They were also beginning to understand the economic importance of engaging local leaders and communities in recruiting students, especially those who the university had historically excluded. This shifting perspective also provided an opportunity for those communities to make requests of or demand changes at UM to create a more inclusive university.

5Conclusion

The University of Mississippi and Oxford have long been intertwined, yet discussions of desegregation frequently silo the university and town away from each other. Focusing on the ways in which Black people navigated and used public (or quasi-public) campus spaces during Jim Crow brings forward the interpersonal and daily interactions threading across the town/gown divide.

As Thomas-Houston points out, Black Oxonians did not participate in mass organizing during or after the civil rights movement. Part of the reason was the extreme White supremacy that, as Susie Marshall recalls, did not allow local membership in the NAACP until the 1970s. Another likely factor was the threat of losing their jobs at UM and being forced away from their Oxford community. This lack of overt organizing and activism did not mean that no one confronted racism, however. Black individuals in and around Oxford resisted Jim Crow in daily interactions, making small ripple effects and supporting Black presences on campus. Black university workers during and after slavery recognized UM’s reliance on their labor. For some, working at UM also meant engaging socially with White people, such as the “shoe shine” gambling with students, or having access to confidential information like Tankersley did as the chancellor’s chauffeur.

For others, the hundreds of Black people whom the university employed in the mid-1900s presented the opportunity to create and sustain Black community across the campus/town divide during a time when Jim Crow attempted to dehumanize Black people into only the worth of their labor. Concentrated in the laundry, sanitation, and cafeteria services, Black UM employees brought community with them by helping relatives and friends become coworkers and by providing lodging for colleagues who needed it. This community-building also framed parts of campus as Black spaces, which stood in opposition to segregation’s assertion that public spaces were actually for Whites only. Furthermore, university police and disciplinary reports surveilling Black people on campus offer glimpses into how Black people—employees and nonemployees—similarly pushed back against their exclusion from UM’s visitor spaces like football games and eating in the cafeteria. Due to de jure and later de facto segregation, Black communities around UM invested in themselves, organizing within and establishing and supporting their own businesses. The success and importance of these endeavors made White communities and government offices like the Chamber of Commerce take notice of and support Black citizens’ and businessowners’ roles in Lafayette County’s economic vibrancy. Once UM began enrolling Black students, local Black communities also invested in and supported them, including when Oxford arrested and UM expelled Black students in 1969–70 for protesting racism on campus.

These possibilities and moments of interpersonal interactions between races and individual acts pushing the boundaries of Jim Crow were small but significant. They did not topple systemic racism or cause an overhaul of policies like that of the civil rights movement and Black Power Movement activism. They were instead a gradual yet perpetual chipping away at White supremacy through reimagined cultural norms and individual relationships. Local Black residents did not see an impenetrable wall between the university and Oxford, but rather used their influence to bring the two closer together.

Notes

I would like to acknowledge the Study the South Research Fellowship, sponsored by the Center for the Study of Southern Culture and the Department for Archives and Special Collections for funding the archival research trip to the University of Mississippi. The research from that trip formed the basis of this work. In addition, I would like to thank the writing group that fostered my writing and provided feedback on drafts: Michele Fazio, Wilson Chen, Maureen Curtin, Maggie Davis, Benji de la Piedra, and Naomi Williams. This group formed out of a 2021 Summer Institute on “The New Deal Era’s Federal Writers’ Project: History, Policies, and Legacy,” funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

- To highlight a few: Nadine Cohodas, The Band Played Dixie: Race and the Liberal Conscience at Ole Miss (New York: The Free Press, 1997); William Doyle, An American Insurrection: The Battle of Oxford, Mississippi, 1962 (New York: Anchor Books, 2003); Charles W. Eagles, The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009); Henry T. Gallagher, James Meredith and the Ole Miss Riot: A Soldier’s Story (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2012); Frank Lambert, The Battle of Ole Miss: Civil Rights v. States’ Rights (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); James Meredith, Three Years in Mississippi (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1966); Kathleen Woodruff Wickham, We Believed We Were Immortal: Twelve Reporters Who Covered the 1962 Integration Crisis at Ole Miss (Oxford, MS: Yoknapatawpha Press, 2017).

- See Will D. Campbell, And Also with You: Duncan Gray and the American Dilemma (Franklin, TN: Providence House, 1997), and Araminta Stone Johnston, And One Was a Priest: The Life and Times of Duncan M. Gray Jr. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010).

- Marilyn M. Thomas-Houston, “Stony the Road” to Change: Black Mississippians and the Culture of Social Relations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- Thomas-Houston digs deeper into the social relations in Oxford and the ways in which Black people in Oxford distanced themselves from Meredith, 56–58.

- Eagles, The Price of Defiance, 18. See also “Meek Dies in Hospital, Author of ‘Ole Miss,’” Mississippian (19 April 1963). For more on gender, race, and lynching, see Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996); Danielle L. McGuire, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance: A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010).

- Extended Sensitivity and Respect Committee, “Report, Findings, and Recommendations of the Extended Sensitivity and Respect Committee,” University of Mississippi (n.d.) accessed November 21, 2023, history.olemiss.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2016/07/SR-Committee-Report-and-Response.pdf, 10.

- “The University’s Enslaved Laborers” contextualization plaque, Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on History and Context, University of Mississippi, accessed November 21, 2023, https://context.olemiss.edu/implementation.

- R. S. Black, “Department of Student Personnel, Daily Report,” September 8, 1948, Franklin E. Moak Collection (MUM00721), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Susie Marshall, interview, 2004, Open Doors Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Willie B. Tankersley and Louise Tankersley, interview by Janet C. Fortune, March 24, 1997, author’s private collection.

- Willie B. Tankersley, interview, 2003, Open Doors Collection (MUM00346), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- For more on how UM’s desegregation increased racial tensions, see Thomas-Houston, 56–59.

- Tankersley and Tankersley, interview.

- Tankersley, interview.

- Tankersley, interview.

- James Meredith, Three Years in Mississippi (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1966), 213.

- Tankersley, interview.

- University and state representatives had celebrated the desegregation of Fraternity Row. UM assistant vice chancellor for public relations and marketing Ed Meek decried the incident, emphasizing instead current interracial efforts and collaborations on campus. The university facilitated a new lease with a nearby vacant fraternity house on the same street, the Ole Miss Interfraternity Council initiated a fundraiser for $20,000 to renovate the vacant house, and Chancellor Gerald Turner reported that alumni at a meeting “start stuffing money in my pockets. They didn’t even give me their name so I could send them a receipt for their tax return.” When Phi Beta Sigma moved into their newly renovated house in October 1988, two dozen White fraternity members helped them. See “Fire Guts Black Fraternity’s House: Mississippi Officials Fear Blaze Will Fuel Racial Tension,” Washington Post, August 6, 1988: A9; “Black Fraternity Getting Help over Burned House,” New York Times, August 7, 1988: A23; William Raspberry, “Rebuilders at Work in Mississippi,” Washington Post, September 9, 1988: A25; “Phi Beta Sigma Integrates Ole Miss Fraternity Row,” Atlanta Daily World, October 18, 1988: 1 and 6.

- Susie Marshall, interview, 2004, Open Doors Collection (MUM00346), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- For more on SNCC, see Hogan, Many Minds, One Heart. Biographies of SNCC’s founder, Ella Baker, also shed light on the organization’s activities. See Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement; J. Todd Moye, Ella Baker: Community Organizer of the Civil Rights Movement (2013).

- Patricia Sullivan, Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement (New York: New York Press, 2009), 79, 425.

- The exact number is difficult to determine because of inconsistent census reporting. While most census workers indicated which individuals worked at UM, at least one only listed the industry (i.e. laundry, cooking, cleaning, etc.) and that the individual was a government worker. It is unclear whether those individuals worked at UM or for another government entity, such as another school, the power plant, or the city itself. 1950 US Federal Census Population Schedules, Enumeration Districts 36-1A to 36-8F, Lafayette County and Oxford City, Lafayette County, Mississippi, Record Group 29: Records of the Bureau of the Census, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, accessed June 9, 2023, https://1950census.archives.gov/search/?county=Lafayette&page=1&state=MS.

- Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning, “The University of Mississippi Fall Enrollment since 1848–1849, Oxford Campus,” Application, Admission, and Enrollment Data Trends, University of Mississippi, n.d., accessed June 12, 2023, https://irep.olemiss.edu/institutional-research/enrollment-data/.

- 1950 US Federal Census Population Schedules, Enumeration Districts 36-1A to 36-8F.

- 1950 US Federal Census Population Schedules, Enumeration Districts 36-1A to 36-8F.

- 1950 US Federal Census Population Schedules, Enumeration Districts 36-1A to 36-8F.

- James Matthew Reonas, “James W. Silver,” Mississippi Encyclopedia (Oxford, Mississippi: Center for the Study of Southern Culture, 2017), accessed September 25, 2023, http://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/james-w-silver/; James W. Silver, Running Scared: Silver in Mississippi (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1984).

- C. L. Marquette, “Monday, May 12, 1958,” Box 12, Daily Journals, 1950–1968, C. L. Marquette Collection (MUM00284), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- 1950 US Federal Census Population Schedules, Enumeration Districts 36-1A to 36-8F.

- Burnes Tatum, “Offense Report,” October 3, 1964, Franklin E. Moak Collection (MUM00721), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Burnes Tatum, “Offense Report,” December 5, 1964; January 17, 1966; and January 22, 1965; Franklin E. Moak Collection (MUM00721), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Burnes Tatum, “Offense Report,” November 16, 1965, Franklin E. Moak Collection (MUM00721), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Soul Force, February 4, 1972, Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Soul Force, February 4, 1972.

- See Charles C. Bolton, The Hardest Deal of All: The Battle over School Integration in Mississippi, 1870–1980 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2005).

- Bolton, The Hardest Deal of All; Susie Marshall, “Oxford Development Association,” “We Cannot Walk Alone”: Images and History of the African-American Community online exhibit, Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi, accessed November 7, 2022, https://olemiss.edu/depts/general_library/archives/exhibits/civilrights/aa/index.htm.

- Soul Force, April 1970, Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Soul Force, March 1972, Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Linnie Liggins Willis, interview by Brittany Brown, February 26, 2020, Oral Histories from Black Power at Ole Miss, accessed November 21, 2023, eGrove, https://egrove.olemiss.edu/blkpower_ohistories/9.

- Linnie Liggins Willis, interview.

- Thomas Brown interview by Jasmine Stansberry, March 23, 2021, Black Families of Yalobusha County Oral History Project, eGrove, accessed November 21, 2023, https://egrove.olemiss.edu/blkfam_yalo/16.

- C. L. Marquette, “Sunday, March 1, 1970,” “Monday, March 2, 1970,” and “Wednesday, February 25, 1970,” Daily Journals 1970, C.L. Marquette Collection (MUM00284), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Porter L. Fortune Jr., letter to Willie B. Tankersley, January 12, 1971, Vice-Chancellor Collection (MUM00651), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- “Lets [sic] Grow Black Flowers,” Soul Force, June 21, 1973, Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi, 4.

- Oxford-Lafayette County Chamber of Commerce, “Board of Directors Regular Monthly Meeting Agenda,” February 17, 1972, Franklin E. Moak Collection (MUM00721), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Oxford-Lafayette County Chamber of Commerce. The board members as listed in the meeting minutes include Garner Hickman, Frank Cooper, R. A. Davis, Howard Duvall, Jr., B. O. Elliott Jr., T. H. Freeland III, J. R. Grimes, Dr. L. G. Hopkins, Sydney Johnson, Robert Khayat, William Lovelady [Sr.], Bon H. McElreath, Gene Meadows, Dr. Frank Moak, Frank T. Ramage, William Henry Tate, Jean Allen Young, and Lester Young.

- Franklin E. Moak, interdepartmental communication to Whitney D. Stuart, November 29, 1965, Franklin E. Moak Collection (MUM00721), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- John Pilkington, iInterdepartmental communication to M. B. Honeycutt, October 18, 1973, Vice-Chancellor Collection (MUM00651), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Oxford-Lafayette County Chamber of Commerce, “Program of Work: 1973–1974,” Franklin E. Moak Collection (MUM00721), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.

- Jerry C. McCall, interdepartmental communication to Porter L. Fortune Jr., June 3, 1974, Vice-Chancellor Collection (MUM00651), Archives and Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi.