1Faulkner in the Delta

There is a particularly striking passage early in the “Old Man” section of William Faulkner’s The Wild Palms that captures in an image of sedimentation a deeply textured metaphor for the wild Mississippi Delta. The main character, known only as the “tall convict,” has served seven years of his sentence at that plantation prison in the Delta, Parchman, for a botched train robbery. Every day he has plowed the earth on his little ordained allotment. Now, just beyond a towering levee, the Old Man, the Mississippi River, is rising through the early spring of 1927 until, in May, the tall convict is loaded on a truck as a member of a chain gang and brought down into the flood itself as part of the futile attempt to staunch it. As he and his fellow prisoners enter the flood zone, the scene is described as follows:

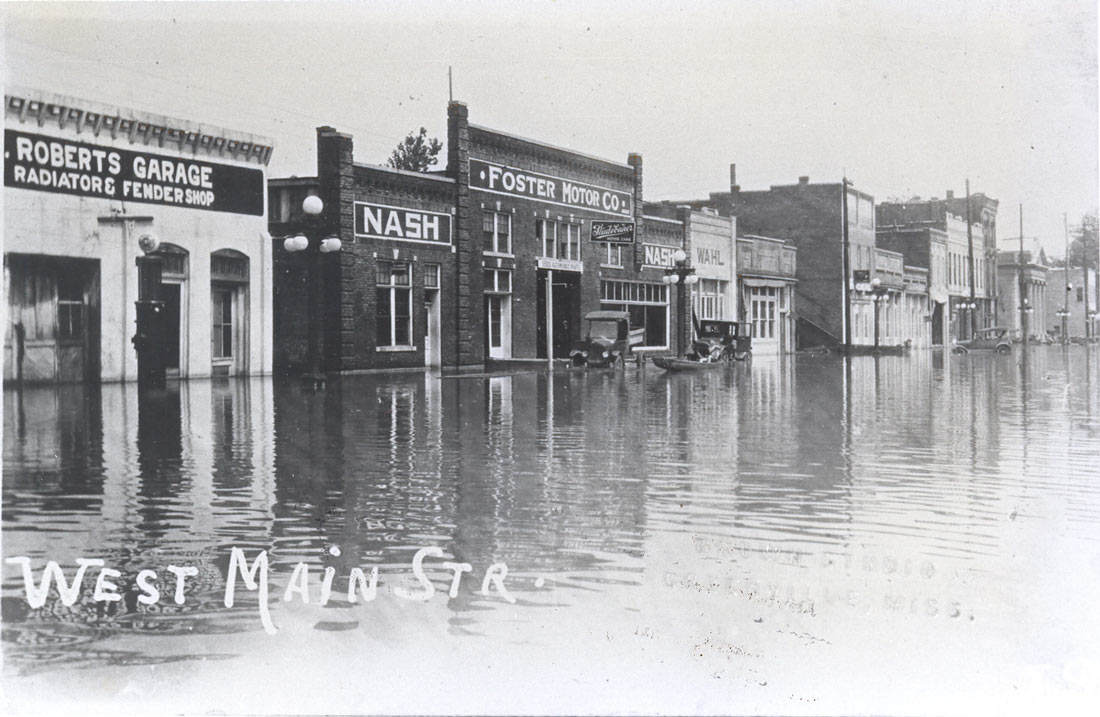

It was perfectly motionless, perfectly flat. It looked, not innocent, but bland. It looked almost demure. It looked as if you could walk on it. It looked so still that they did not realize it possessed motion until they came to the first bridge. There was a ditch under the bridge, a small stream, but ditch and stream were both invisible now, indicated only by the rows of cypress and bramble which marked its course. Here they both saw and heard movement—the slow profound eastward and upstream (“It’s running backward,” one convict said quietly.) set of the still rigid surface, from beneath which came a deep faint subaquean rumble which (though none in the truck could have made the comparison) sounded like a subway train passing beneath the street and which inferred a terrific and secret speed. It was as if the water itself were in three strata, separate and distinct, the bland and unhurried surface bearing frothy scum and a miniature flotsam of twigs and screening as though by vicious calculation the rush and fury of the flood itself, and beneath this in turn the original stream, trickle, murmuring along in the opposite direction, following undisturbed and unaware its appointed course and serving its Lilliputian end, like a thread of ants between the rails on which an express train passes, they (the ants) as unaware of the power and fury as if it were a cyclone crossing Saturn.1

William Faulkner, that great voice who raised what he called his “postage stamp of native soil” to the heights of mythic significance, only rarely wrote about the most mythic space in his native state of Mississippi, the Delta. Born in New Albany, a town in the heart of the hill country, and raised in Oxford, his life resided mostly east of the great line of bluffs that stand sentinel over the low bottomland of the Delta. To understand the basic geography of the state north of Jackson, one can follow Interstate-55 south out of Memphis. The long road traces the line of those bluffs, which form the edge of the hill country much like the broken edge of a giant bowl scoured by old streams that finally cut loose in the oversized bottomland that is the Delta, the source of the yearly flooding that, over countless centuries, made the region so prosperous for farming yet so fickle for human habitation.

Oxford is twenty-five miles east of the interstate, its famous courthouse sitting atop a high ridge roughly equidistant between the Tallahatchie and Yocona River Bottoms on the north and south borders of Lafayette County. New Albany is farther east still, near the headwaters of the Tallahatchie and high in the pinewoods of the Holly Springs National Forest. In 1927, the year of the Great Flood, after having published a novel set in Georgia and another in New Orleans, Faulkner began work on material that would later become Flags in the Dust (originally published as Sartoris), which he set in what he called at the time Yocona County, bordered on its north and south respectively by the Tallahatchie and Yocona Rivers. Later, he would rename the county Yoknapatawpha County, and the river on its southern edge Yoknapatawpha as well, though the northern border would remain the Tallahatchie River, a trace of the original Lafayette County in the transposed geography of Faulkner’s grand myth.

Faulkner described the creative leap in which he turned to his home in Mississippi as the setting for his fictional universe as “discover[ing] that my little postage stamp of native soil was worth writing about and that I would never exhaust it, and by sublimating the actual into the apocryphal I would have complete liberty to use whatever talent I might have to its absolute top” (qtd. in Blotner).2 So he effectively turned Lafayette County into Yoknapatawpha County, especially in novels set in its southeast corner in a settlement he names Frenchman’s Bend, about the hill country people like the Snopeses and the Bundrens and the hard-scrabble life they lead there. However, this transposition of actual Lafayette to apocryphal Yoknapatawpha does not leave much room for the Delta since, as Lafayette County is not a Delta county, it is difficult to imagine how the Delta might fit into the Yoknapatawpha that was born from it.

But one could reasonably argue that the Delta underlies everything in Mississippi—the politics, the economy, the culture, the sense of native identity—so of course it shows up in Yoknapatawpha County, if one knows where to look and listen carefully for it. To understand how Faulkner brought the Delta into his apocryphal creation, one has to understand what I would call Faulkner’s impressionistic geography, his sense of the interwoven texture of the disparate parts of the landscape, a sense not unlike an old Roman artisan who can see in the discreet piles of broken same-colored pieces of tile the grand and seamless mosaic he means to put upon the master’s wall. We mere mortals may have a more difficult time seeing the whole so seamlessly, but I’ll try to tease out a basic outline here, not a fully formed mosaic masterpiece, but at least the basic shape of what that better genius of Faulkner’s fashioned with such marvelous depth and resonance.

The best place to start our own way into an understanding of this impressionistic geography is to start with Faulkner’s actual experiences in the Delta, his familiarity with life there, and the actual map of his submergence into it. As I’ve said, Faulkner was born in New Albany, Mississippi, in Union County, in the eastern portion of the state often referred to as hill country. When he was five years old, his family moved to Oxford, a thirty-mile trek west into country still generally considered hill country but approaching the Delta, ever so slightly, especially along the route of the Tallahatchie River arching along the northern border of Lafayette County where Highway 7 crosses the river on its way to Holly Springs. In the 1930s, the army corps of engineers dammed the Tallahatchie farther west still, in Panola County, near the town of Sardis. Much of the low-lying bottomlands that once occupied northern Lafayette County are lost on contemporary maps of the state. During a particularly wet spring, the bloated Sardis Lake can cover well over thirty miles of backed-up river bottom, flooding even to Abbeville, a small community north of Oxford that transposes into Faulkner’s fiction as part of Yoknapatawpha County called Beat Four. The wide and low expanse of the former river bottom, that is now lake bed, would have had a feel very similar to the larger wilderness of the Delta, which begins in earnest on the western side of Panola County. Before the area near Sardis was flooded, though, Faulkner would have had to cross through it every time his family went north to Memphis. Faulkner probably had something of this old stretch of Tallahatchie Bottom in mind when, in his last novel The Reivers, he wrote that small masterpiece of American humor about Hell Creek Crossing.

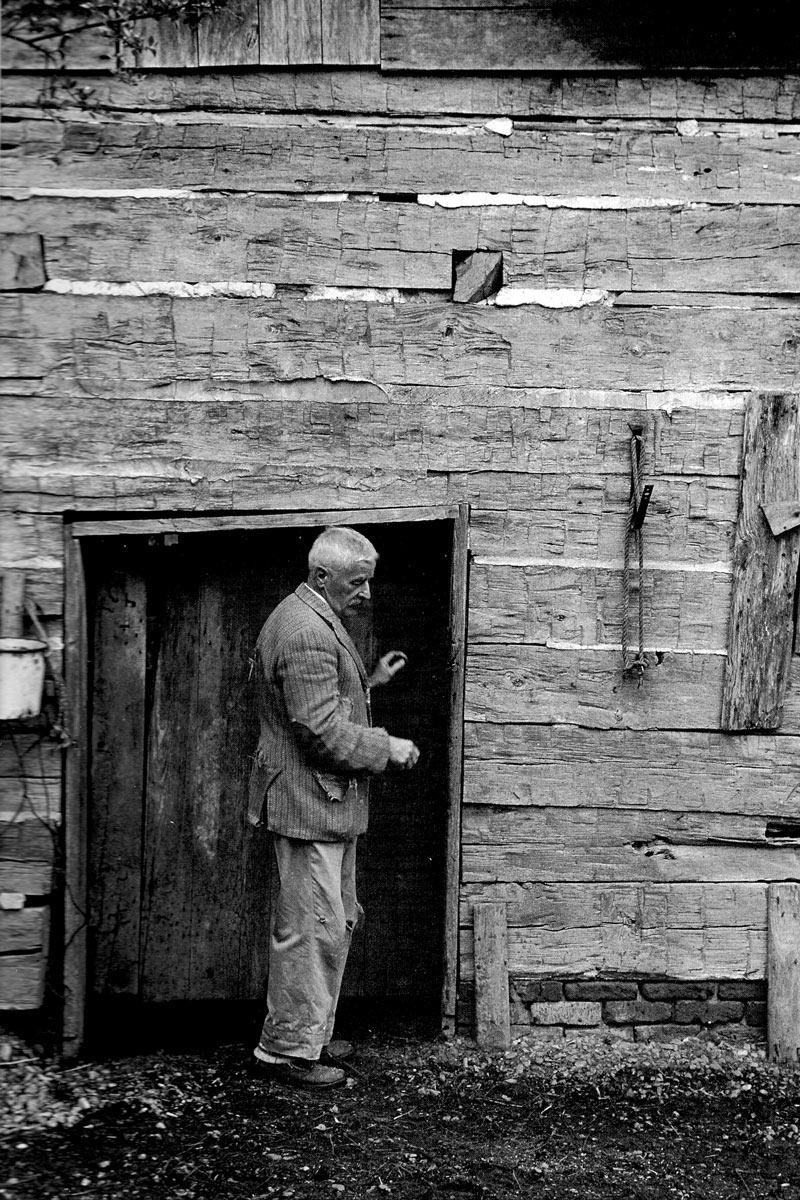

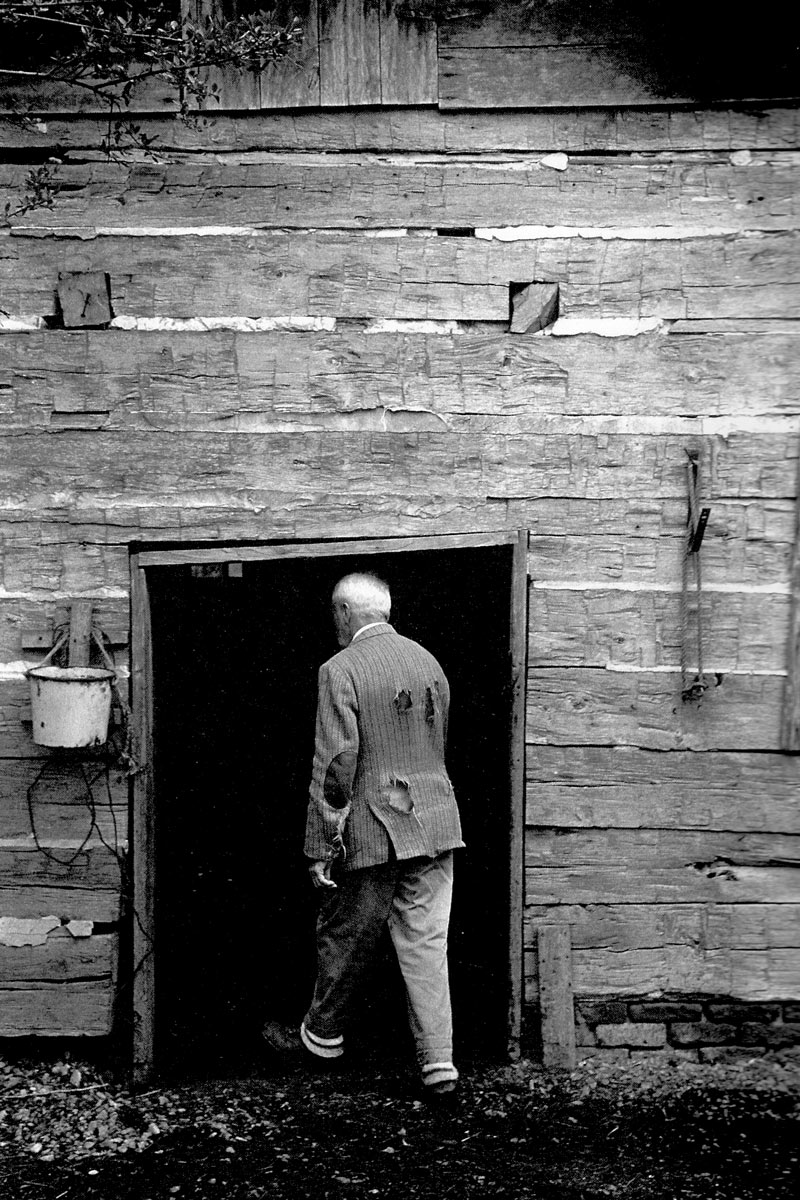

In general, any trip during his childhood to Memphis would put Faulkner in close proximity to the bottomland of the upper Delta region, but by far his most direct known submergence in it would not have occurred until the mid-1910s or early-1920s, after he had befriended another Oxonian named Phil Stone. Stone would prove to be the seminal influence on the young Faulkner’s literary career; the Ivy-league-educated Stone would pass on to Faulkner his editions of the newest modern poetry, or they would chew the fat over their mutual appreciation for the French writer Honoré de Balzac. Far more relevant to Faulkner and the Delta, it was Stone’s father who owned the hunting camp and a huge tract of land in the Tallahatchie River bottom where Faulkner would retreat throughout his life to hunt, among other animals, deer, bear, and fowl. But Faulkner, though he clearly loved to spend time in the bottom during hunting season, went as much for camp life as for skillful hunting. As his biographer Joseph Blotner explains, while Faulkner in camp would look “hardly indistinguishable from the other [hunters] in his stained hunting clothes and worn slouch hat,” his real interest lay in the stories he heard there. For though he told some stories himself, “most of the time he would listen” to the other men in their shared local idiom swap old tales between each other. We might allow ourselves the luxury of imagining some of these stories, perhaps about a spirited fyce or a part-bluetick mongrel of mythic size and strength, about an old bear seemingly immortal, or about the ghostly shapes of Indian mounds shrouded in the mist of early morning. The backbone of Faulkner’s greatest Delta stories are fundamentally stories about camp life and the November hunt.3

We do not know precisely where the old Stone hunting camp was in the Tallahatchie River bottom. We do know it moved—not by choice but by necessity. After the Great Flood of 1927, the federal government instituted a new flood control system that included the construction of massive earthen dams on the Coldwater River at Arkabutla, the Tallahatchie at Sardis, the Yocona at Enid, and the Yalobusha at Grenada, the four great tributaries of the Yazoo River all staunched upriver to make farming downriver less perilous. The dam at Sardis, built in the 1930s, flooded the region where Faulkner most likely hunted in the 1920s. By the 1940s and 1950s, he had to travel farther and farther west into Panola County to find wilderness isolated enough to harbor the game that made such serious hunting expeditions worthwhile. To this day, the stretch of land from eastern Lafayette to western Panola Counties remains rural, even by Mississippi standards. On I-55 between Batesville and Hernando, one cannot help but get the impression of a vast and formless space dotted only occasionally by small outposts such as Como, Sardis, and the town of Coldwater. Otherwise, the huge lakes that flood the landscape have kept much of the interior regions of the old Tallahatchie and Coldwater river bottoms denuded of inroads and large highways. Between Sardis and Como, one can even see deer stands from the interstate. These are hardly a heartening sight, and they leave one feeling that perhaps, even in a car, it would be best to wear a bright orange hat while passing through, just to be safe.

Few influences on Faulkner’s sense of a Delta are as profound as his trips to the Stone’s hunting camp, but these are not the only entry Stone gave Faulkner to the Delta. In the early 1920s, having returned from flight training in Canada during World War I and finding himself sort of stuck in Oxford, Faulkner joined Stone for his escapades to Clarksdale, where Stone had befriended a man whom biographers refer to simply as “the Clarskdale gangster Reno DeVaux.” These escapades, during the prohibitionist 1920s, took DeVaux, Stone, and Faulkner as far north as Memphis and its red light district on Gayoso Street, South of Beale. At least according to anecdotal evidence gathered from interviews, Faulkner never partook of the horizontal refreshments offered upstairs in the whorehouses in Memphis but contented himself with a drink and conversation downstairs, even at one point begging off an invitation by an “employee” with the respectful “No thank you, ma’am. I’m on vacation.”4 DeVaux is also generally credited with sponsoring Faulkner’s first trip to New Orleans in the early 1920s, establishing the connection to that city Faulkner would later follow to move there in 1925, where he’d write his first novel. As far as impressionistic geographies go, these episodes lend credence to the claim that the two biggest cities in Mississippi are Memphis and New Orleans. Conveniently, it took a man from the Delta to show Faulkner the, shall we say, “better” sides of both.

A more respectful entry to the Delta that Stone afforded Faulkner were visits to Charleston, Mississippi, west of the interstate about as far south as Enid Lake and Water Valley. The Stone family operated a branch of their law firm in Charleston. When Phil Stone found himself living in Charleston to run that branch, Faulkner would visit to play a round of golf or to court Stone’s secretary at the time, though according to Faulkner’s brother John this courtship was thoroughly chaste. The secretary and Faulkner got along and even traded gifts through the mail, and the girl would dutifully monogram handkerchiefs for Faulkner—her supposed beau—but in a box of six, she never seemed to get past monogramming the first one or two. Faulkner later regretted that he had led the girl on.5

The nexus of stories involving Stone center around the northeastern reaches of the Delta, along the Tallahatchie River and its drainage basin. These stories are only part of Faulkner’s Delta experiences. The other significant influence came out of Greenville, hometown of one of Faulkner’s lifelong friends, Ben Wasson. Wasson was a few years younger than Faulkner and an undergraduate at the University of Mississippi when he met Faulkner in Oxford before World War I. Wasson went on to become a law student and friends and fraternity brothers with Faulkner after the war. Together with Ella Somerville and later Lucy Somerville—also Greenville natives—Wasson and Faulkner helped found a campus theater troupe, the Marionettes, for which Faulkner wrote a play in 1921. When Wasson graduated in 1921, he returned to Greenville to work in his father’s law firm. Having little to preoccupy him in Oxford after he withdrew from the university in the fall of 1920, Faulkner visited Wasson in Greenville sometime in the summer or early fall of 1921. On that visit, Wasson introduced Faulkner to his friend, the poet William Alexander Percy. The meeting did not go well. While still a student at Ole Miss, Faulkner had written a review of Percy’s collection In April Once that faulted Percy’s old-fashioned style.6 The review is subtle and carefully critical, not openly hostile, but Percy seems to have taken exception to it. He received Faulkner at his home with Wasson icily, but Wasson, in his memoir, concedes that maybe this reception had less to do with the review, more to do with the fact that Faulkner was red-faced with drink and barefoot, and, when asked to play a game of tennis, proved so obnoxious that Percy suggested Wasson take him home.7 Later, in November of 1921, Percy and Faulkner would cross paths in Greenwich Village in New York. According to Blotner, this meeting proved jovial and even affectionate, as if the two men were old friends from back home in Mississippi, though it does not appear they were or at least they had a very strange way of showing it.8

The Greenville native Wasson would play an important role in Faulkner’s life, particularly in the late 1920s when Wasson himself abandoned his life as a lawyer to make a foray into the literary world of New York. He wrote one novel himself, titled The Devil Beats His Wife, but his real contribution to literature was as Faulkner’s agent. Wasson edited Flags in the Dust in order to get the publishing house Cape and Smith to accept it (they chose the new title Sartoris), and though he angered Faulkner when he attempted to edit The Sound and the Fury to make it clearer—not an enviable task by any stretch of the imagination—he also managed to recruit Evelyn Scott to write a brilliant review of the novel to bolster Faulkner’s literary reputation. Wasson later recruited the radio personality Alexander Woollcott to sing the praises of Sanctuary on his immensely popular radio show The Town Crier. Wasson credits this attention by Woollcott for the commercial success of Sanctuary, Faulkner’s bestselling novel prior to his winning the Nobel Prize. Some critics claim Popeye, the twisted gangster at the heart of that novel, is modeled loosely on Reno DeVaux. To the extent such a claim is true, then the influence of the Delta is twofold in the novel: the agent who helped sell it and the man at its core. Below the surface of Faulkner’s career, the Delta emerges in such strange but fascinating places.

The one most important biographical element of Wasson’s influence on Faulkner, though, may well be a visit Faulkner made to Greenville in 1924. Carrying with him a copy of Sherwood Anderson’s Horses and Men, Faulkner walked with Wasson to the top of a levee overlooking the Mississippi River. He read aloud the story “I’m a Fool” and then told Wasson that he’d like to meet Anderson. Wasson related that, according to William Alexander Percy, Anderson was in New Orleans. Faulkner and Wasson began to scheme a way to meet Anderson using Percy’s connection to Anderson’s wife, Elizabeth Prall. This meeting would take place in late 1924; Faulkner would move to New Orleans in early 1925. There he’d write his first novel and begin the process of becoming the great author we know him as today. Yet, as they schemed, Faulkner paused and turned his attention to the river. As he and Wasson watched the sunset, Faulkner exclaimed, “Listen! You know what the Old Man is saying. ‘They’re not going to tame me.’ And nobody ever will.”9 Faulkner would prove prophetic. On just such a levee near Greenville, people would cling to life during the Flood of 1927. That same year Faulkner would begin his series of Mississippi novels that would go on to redefine the very nature of narrative technique. Within his fiction, the impression made by the Delta bottomland and its mighty river on Faulkner’s imagination would hold as the bottom rung on which he would gird so much of his fiction, as an untamed wilderness always at the edges of vision, the lowest register of sound audible to the ear.

2The Delta in Faulkner’s Work

Though Lafayette County, as an actual place, does not expand quite far enough to encompass the Delta, the apocryphal Yoknapatawpha does. If the southeast corner of that county represents the vast hill country of the eastern side of Mississippi, then the open wilderness on the northwestern edges of Yoknapatawpha exceeds the merely manmade boundaries of a county line to include the entire mythic dimension of the Delta into which the waters of the Tallahatchie flow, ever westward, ever farther and farther on. Faulkner would turn his attention to that northwestern wilderness throughout his career, eventually recording a history for it that spans from its final years of Indian occupation to its flooding in 1927 (or, in the case of the Sardis region, its “reflooding” when the dam was built in the mid-1930s). One can follow the strain of that apocryphal Delta in the wilderness along the Tallahatchie River in Yoknapatawpha County as a chronological strain flowing east to west in retreat from the encroachments of the modernized, industrial inroads of man and his vain attempts to tame it. While bits and pieces of this narrative of the Delta crop up throughout Faulkner’s fiction, the four books that best epitomize it are Big Woods, Absalom, Absalom!, Go Down, Moses, and The Wild Palms, which includes the novella “Old Man.” Also, he records the history of the bottomland and its earlier inhabitants in the short stories “Red Leaves,” “A Justice,” and “A Courtship,” all of which Faulkner included in his Collected Stories. Unfurled, these novels and stories present a Faulknerian history of the Delta.

Strictly speaking, Faulkner’s Delta is never a pure and pristine virgin wilderness. Ike McCaslin, in the long version of the story “The Bear,” explains his decision to repudiate his inheritance and familial claim to the land based on an assumption that there was at some point a pure land prior to mankind’s pretense of owning it. While certainly in theory such a space existed at some point in the longer geological history of the Delta, even when Faulkner begins his history of his Delta with the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians, he includes mention of older Indian mounds that archeological evidence can date to Mississippian Indian cultures vastly older than either of those two peoples. Faulkner’s Delta begins, more or less, the day a Chickasaw chieftain, Issetibbeha, dies. His death is watched by—but not attended by—his manservant, a “Guinea man,” or an African slave who can still recall his journey through the Middle Passage as a young boy before his lifetime of servitude in Issetibbeha’s court. When Issetibbeha dies, his slave is expected to join him in death; naturally, the slave runs for his life through the vast river bottom in which his enslavers have built a settlement that Faulkner even calls a plantation, or a stretch of cleared land for raising crops along the bottom of a tributary that, with slaves and a strict social hierarchy, approximates the social conditions that will later define white settlement in the Delta years later. The slave runs for several days; the Indians give chase, but only as a formality and with no display of speed or enthusiasm. They see the chase as part of the ritual, and when they do finally catch the slave, they even congratulate him on a good run. The slave has been unable to escape because the wilderness surrounding him—though a small plantation is carved into the middle of it—is so dense and remote as to be inescapable.

Issetibbeha’s death leaves a bit of a quandary of succession for the Chickasaw. Eventually, an Indian known only as “The Man” makes a move for power, though he does this by going to New Orleans to employ a French-speaking Creole aristocrat who calls “The Man” in French “du homme,” which the other Chickasaw mishear not as two separate words but as simply the one English word “Doom.” Doom sees all of his people as slaves and sets about creating more than just a plantation in name but actually a plantation in design as well. He orders his “people” to retrieve an abandoned riverboat and haul it overland to make an actual plantation house. The riverboat used to travel up the tributary during the spring floods, but one year it failed to return downriver in time and was stranded and eventually abandoned by the company that owned it.

The details of this ersatz plantation are important in Faulkner’s imagining of the Delta because, typologically, they bear tremendous significance for all that will follow along this stretch of ground in the Tallahatchie River Bottom. Doom, or “The Man,” would be the chieftain responsible for selling his land sometime in the 1830s to Thomas Sutpen, a new arrival in the newly established county of Yoknapatawpha. The patriarch of Faulkner’s masterpiece Absalom, Absalom!, Sutpen arrives in the Mississippi wilderness seemingly out of nowhere. We eventually learn that, though he was born a poor white in the mountains of western Virginia, he has made himself rich through a previous marriage to a rich planter family in Haiti. He carries into the untamed Mississippi wilderness an unwavering drive for fortune and the dream of creating his own dynasty. He means to do so with a group of rough, French-speaking slaves who help him clear the dense swampland and a refined French architect whom he pays to live out in that swamp for three years to help design and build his ideal planter’s home. At one point, the French architect, recognizing that he himself is a slave, flees into the swamp. Sutpen, re-enacting the chase for Issetibbeha’s Guinea man, trees the architect like a squirrel and brings him back to finish the job. The chase is slightly more exciting than the one for Issatibbeha’s man, but only slightly. The swampy bottomland is still inescapable, still dense jungle waiting for a man strong enough to wrest from it a small plot of earth and establish a home for as long as he can before the wilderness of canebrakes and cypress trees re-encroaches.

James Cobb, in his masterful history of the Delta, correctly points out that Sutpen might be the mythic image of the great Delta planter, but he is not the reality.10 Sutpen was born poor; to clear the land in the Delta required the money to invest in slaves as capital and underwrite cotton production on what was effectively an early derivatives and futures market. Poor men did not come to the Delta and make themselves rich; rich men came to the Delta to get richer. Faulkner wisely sidetracked Sutpen to Haiti to get the capital necessary for his meteoric rise to the heights of the antebellum southern planter’s dream. But his poor-white roots show. He hires a man named Wash Jones as a kind of overseer. Sutpen can often be found sitting behind his “big house” in his scuppernong arbor with Wash and talking in their mutual poor-white idiom (as an example of what this might sound like, we must imagine that “Wash” would actually be pronounced “Warsh” and then fill in the rest of the dialect from there).

After the war, and after Sutpen’s plan has completely unraveled, he turns to Wash and courts Wash’s granddaughter. When this courtship fails, Wash kills Sutpen. The old plantation house falls into disrepair and eventually burns. All that’s left of Sutpen’s Hundred, the old plantation in the Tallahatchie Bottom, is Wash Jones’s old cabin right on the river. If we read closely into Faulkner’s various hunting stories, we can see that it is precisely this cabin that Major de Spain buys and turns into the hunting camp in the “Big Bottom” where he, Mr. Compson, Cass Edmonds, Boon Hogganbeck, Ike McCaslin, and Sam Fathers retreat every November for a two-week hunt. They hunt all sorts of game in the bottom, but they are always keen on one particular animal, a bear so mythic as to have its own name, Old Ben. The wilderness in which Faulkner places his story “The Bear” is the same wilderness where Indians once chased a slave and hauled a riverboat to make a plantation house; where Sutpen broke the land to create his own small dream; where now only vague traces of those older attempts at taming the land remain—the cabin, mostly—in a land that has regrown and resubsumed the pitiful inroads of man’s attempts to make civilization out of it.

In “The Bear,” and in the stories collected in Big Woods, Faulkner offers his most powerful evocation of the Delta and its history from the 1870s to the early 1920s, a time James Cobb also identifies as its boom years, the Renaissance of its perfection as the rich cotton country of our contemporary imagination. The story follows a sixteen-year-old Ike McCaslin into the Delta for the last great bear hunt. Ike enters the wilderness of the “Big Bottom” in a surrey,

moving through the skeleton stalks of cotton and corn in the last of open country, the last trace of man’s puny gnawing at the immemorial flank, until, dwarfed by that perspective into an almost ridiculous diminishment, the surrey itself seemed to have ceased to move [. . .] as a solitary small boat hangs in lonely immobility, merely tossing up and down, in the infinite waste of the ocean while the water and then the apparently impenetrable land which it nears without appreciable progress, swings slowly and opens the widening inlet which is the anchorage.11

But the wilderness is only “apparently impenetrable.” Boon will kill Old Ben. The old Chickasaw hunting guide, Sam Fathers, dies at virtually the same time. Within two years of killing Old Ben, Major de Spain has sold the old hunting camp to a logging company. When Ike travels to the old camp two years later, he finds in its stead a lumber mill and newly laid railroad. He finds Boon hunting squirrel in the one remaining tree in a vast clearing, the tree teaming with squirrels because it is the last place they have for refuge. Boon warns Ike clear with the hoarse exclamation, “Get out of here! Don’t touch them! . . . They’re mine!”12 Indeed, he should feel proprietary. This is all that is left of that old wilderness, one tree full of trapped squirrels.

Ike continues hunting the wilderness well into his seventies, though to do so he must travel to “what remained of the big woods further and further southward into the V of the River and the hills.”13 The journey to hunt, which formerly involved a half day on a horse, now requires hundreds of miles of overland travel to the far reaches of the remaining untamed bottomland, as “the wilderness dwindled southward into the notch of the hills and the Old Man.” Ike laments this regression, seeing in it only a cycle of industry and capital: “the timber which had to be logged and sold in order to deforest the land in order to convert the soil to raising cotton in order to sell the cotton in order to make the land valuable enough to be worth spending the money raising dykes to keep the river off of it.”14 In this new world carved from the Delta, Ike will be keenly aware of the layers of history undergirding it and the currents moving through it. He describes this “new” Delta in the story “Delta Autumn,” in what seems to be Faulkner’s nod to John of Gaunt in Richard II describing “this scepter’d isle, This England,” only with less a tone of praise. Ike expounds,

This Delta. The land which man has deswamped and denuded and derivered in two generations so that white men can own plantations and commute every night to Memphis and black men own plantations and ride in jim crow cars to Chicago to live in millionaire’s mansions on Lakeshore Drive, where white men rent farms and live like niggers and niggers crop on shares and live like animals, where cotton is planted and grows man-tall in the very cracks of the sidewalks, and usury and mortgages and bankruptcy and measureless wealth, Chinese and African and Aryan and Jew, all breed and spawn together until no man has time to say which one is which nor cares.15

But Faulkner, if not Ike, knows the final score of these changes. As the inroads of man push farther and farther into the V of the river, that notch of finally untamable Delta wilderness, they come to rely more and more heavily on the optics of control. They build mighty levees to hold back the natural yearly cycle of flooding and even model a prison on a planation, a fitting model in the Delta and one with deep roots. Within the walls of that prison, a tall convict can plow his little piece of earth in that Delta, indifferent to the shadow of the levee towering over him until, in 1927, when the levee breaks.

In “Old Man,” we follow the tall convict on a surreal journey into the Great Flood of 1927. When he is sent to rescue a pregnant woman caught in a bramble, the current pulls his skiff into the flood and shoots him downriver, past Vicksburg and beyond the Delta into the heart of the main current of the Mississippi and even down farther, into the giant basin of the Atchafalaya and the untamed swampland there, and farther still, down to the very mouth of the Mississippi below New Orleans. The tall convict follows the great path of the mighty pipework of the center of the continent from agrarian Delta to the sea. Then, slowly, methodically, the tall convict pushes himself back upriver, intent on returning to Parchman, which he considers a much easier, more predictable life than life out in the real world. As the flood recedes, the tall convict considers his adventure from the vantage point of a hapless survivor. He looks out over the mighty river that “had recovered from his debauch” and slowly drained “back in banks again” once more to “rippl[e] placidly towards the sea, brown and rich as chocolate between two levees whose inner faces were wrinkled as though in a frozen and aghast amazement.”16 In “Old Man,” Faulkner likens the Mississippi River to an old man going on a debauch and, in his drunken debauchery, spilling out of his confinement and reminding those who live in his shadow that they need always remember their precarious insignificance when the old man grows tired of control and predictability. Faulkner celebrates the Old Man’s debauchery with the Dionysian glee of happy Greeks, happy that their gods are thoroughly human and thoroughly unpredictable.

It was largely as a result of the 1927 flood that in the 1930s Faulkner would watch the old Tallahatchie River bottom flooded for the dam at Sardis, a slow, unfolding construction project contemporary to his writing Absalom, Absalom!, “Old Man,” and the hunting stories collected in Go Down, Moses and Big Woods, most of which he wrote from around 1935 to 1942. As he recorded the Delta in his apocryphal county, he was watching the upper reaches of its footprint disappear from the geography, replaced by the lakes that now dot North Mississippi. Yet Faulkner knew the land, and no new features could ever subsume his consciousness of it or the deeper, underlying memory of an older, wilder space within it. When he turned the actual into the apocryphal to create his mythic Yoknapatawpha County, he placed deep in its history an image of the Delta, moving, shifting, always on the edge of man’s teetering existence, but always ever-so-slightly perilous and uncontrollable, beyond man’s ability to tame it into submission even as he clears a patch of land within it to live on and try to make something for himself bigger than what he started with. Still, as the wilderness moves farther and farther into the recesses of the landscape, there is always a sense that one good flood can reclaim the land for the wilderness. The sense that this destruction and reclamation can happen always lingers below the surface. We still value the high ground; we still maintain our levees; we still rely on our huge earthen dams.

Perhaps, though, this is why Faulkner can elevate his county to the level of myth and why the Delta itself can retain that mythic sense of being a special space, different from anywhere else in the world, even from anywhere else in Mississippi. For if the purpose of myth is to create order so as to understand the more mysterious qualities of our origins, then there must always remain below the surface that subcutaneous element on which to build upward our sense of self and of our place in the universe. It is an element at once terrifying and delightful, and exactly the stuff that makes the best stories worth telling at all.