For reasons that are not entirely clear, I’ve long been attracted to rural areas and the small towns that dot the rural landscape. Perhaps it’s because I spent many childhood summers on the semi-rural edge of a small southern city, away from my school-year home in suburban New Jersey. My memories of that time, no doubt somewhat idealized, have me wandering the North Carolina countryside with several of my cousins—riding bicycles on country roads, exploring the nearby woods, smoking pilfered cigarettes, and practicing basic baseball skills. (There weren’t enough of us to play a game.) All of this fun was subject to no particular clock or calendar, much in contrast to the September-through-June routine of school, Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts, piano lessons, and organized sports in New Jersey. As I grew older, the summertime pattern, in memory at least, became a template for happiness; the school-year pattern less so.

In the years since, I’ve lived in several parts of the United States, sometimes in rural areas, sometimes in small cities (usually college towns) with countryside close by. As I grew into my photographic calling, these areas and their small towns became places in which, and about which, to make pictures. I have many such photographs from western Oregon, central Texas, and, most recently, the rural mid-South, especially north Mississippi, where I’ve lived since 1999.

In the fall of 2019 I had heart bypass surgery. In the spring of 2020, just as I was feeling recovered from the surgery, the covid-19 pandemic emerged, along with the need to stay apart from other people and to avoid long-distance travel. Luckily for me, I was able to safely continue making my rural/small town photographs. Depending on weather, I could get out of town to photograph several times a month and, sometimes, during the very best days of autumn and spring, I was able to get out more than once a week.

My habit was to drive back roads, explore, and not worry about getting anywhere quickly or about getting lost. With my wife, Marianne, often accompanying me, we would stick to county roads, always on the lookout for places of visual interest. Among the places we frequently stopped were small towns—in both business and residential areas—and, especially, rural churches and cemeteries. Many of the churches, whether still active or not, had burial grounds close by, and even long-abandoned churches sometimes had cemeteries that showed signs of recent use. A few cemeteries were off by themselves, however, apparently forgotten by any church that might once have been nearby. Some of these more isolated sites were family plots, not necessarily attached to a church.

I found the cemeteries satisfying places to make photographs. Perhaps this was due to a generalized, society-wide awareness of death during the covid-19 pandemic. It may also have been related to my own recent surgery. In any event, the cemeteries often seemed places of beauty, sadness, and religious faith, evoking not only a local past but also a rural culture that while still alive in the present moment was gradually, inexorably fading away. In short, the cemeteries provided a record of a society in the process of becoming a remnant of its past self.

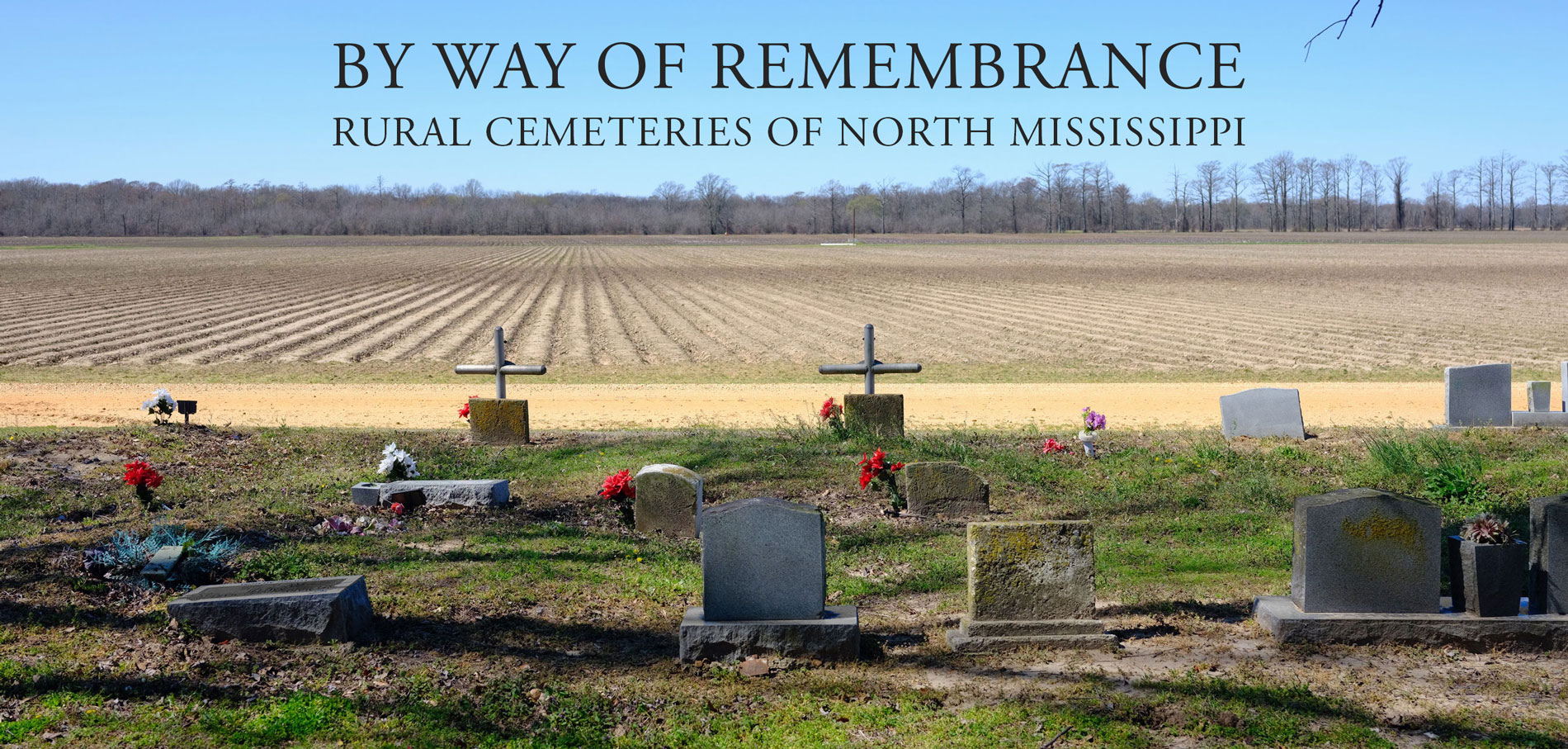

In terms of physical appearance—that is, the visual, or that which can be photographed—these cemeteries fall into two general categories. Some are self-contained and offer little sense of the world beyond. In these places one sees tombstones, decorative plastic flowers, a variety of objects left at gravesites, perhaps a church connected to the cemetery, and not a great deal more. With only a few exceptions, these cemeteries could be in many rural parts of North America.

Others, however, are clearly connected to the larger landscape, both physically and culturally. As with nearly all cemeteries, these locations provide a few brief facts about the individuals buried there, but they also more broadly suggest the world those people lived in. In rural parts of north Mississippi, that world has long revolved around agriculture, and that visual fact is apparent as one looks out past the cemeteries’ boundaries. In these burial grounds, local history lives not only in what is inscribed on the headstones, but in the landscape as well.

The words engraved on tombstones are usually few: the name of the deceased, birth and death dates, sometimes a scriptural passage or a line or two of sentimental verse. One more expansive example of a life story, although told in minimal language, is the marker for one Carrie Cooks of Tallahatchie County. It reads as follows:

Carrie

Cooks. Died

Aug 11 1947 Age 87

Left to Morn 5

Girls 2 Boys 1

Brother 1 Sister

An Host Grand

Children

But Ms. Cooks’s marker is an exception. More typically, information on a tombstone about who the deceased was in life takes the form of illustration, imagery, or sometimes a photograph.

Gravesites often tell more than what appears on the tombstone. Additional facts about what was important to the deceased, or to whom he or she was important, surround many tombstones, creating shrines to the departed and keeping alive the memories friend and family have of them. Such displays often include items rooted in pop culture, references to hobbies or favorite athletic teams, small items of clothing (frequently hats or shoes), indications of political belief, or recognition of devoted pets. Many such arrays are continually refurbished, sometimes expressed in seasonal motifs. Especially touching are displays that emphasize the role the deceased played in the lives of those left behind. Typically, these seem the work of grown children mourning a parent. Most gravesite shrines of this nature seem fairly recent. Not surprisingly, older memorials are usually limited to the tombstone, with whatever was once engraved on it now illegible and gravesite items scattered by time and weather. And in some cases, it seems, there was little or nothing to know, or tell, at the time of the deceased’s passing.

Like any burial ground that reaches back into the nineteenth century, the rural cemeteries of north Mississippi include great numbers of deceased children. As touching as many of the memorials to adults often are, the graves of children tug extra hard at the heartstrings. One cannot help but recognize the lost potential of each of these young lives and sense the devastating sadness of parents who have had to bury their children. Their grief seems almost inexpressible, though many try to give it voice through the tombstones and gravesites they create for their offspring. Stuffed animals and any number of other toys adorn these memorials, as do miniature statuary, religious imagery, and references to games their children once played. And yet, there still seems an emptiness, a vacancy, to these places that no attempt at embellishing can fill up.

Unsurprisingly, these cemeteries display a great deal of religious awareness. The end of life, of course, is when eternity begins, and how one’s soul will spend that never-ending stretch of time is central to many forms of spiritual belief. The iconography and sentiments expressed in north Mississippi’s cemeteries are overwhelmingly Christian and Protestant. One encounters crosses in a variety of styles, angels large and small, passages of scripture from the Old and New Testaments, and an occasional likeness of Jesus. The belief that the deceased and those left to mourn will one day be reunited is expressed repeatedly, largely taken as an article of faith.

If it weren’t for an excess of artificial flowers, most of north Mississippi’s rural cemeteries would lack much in the way of vibrant color. This seems true even on days of bright sunshine, blue skies, and lush green foliage. Most of these flowers are plastic. A few are woven fabric. They proliferate, in abundance, nearly everywhere the eye can see. They cover graves, they adorn tombstones, they exist in flamboyant bouquets, they “grow” singly out of small urns. They are unnaturally bright when new, then slowly fade as the sun ages them. Eventually, the weather gets to them as well, with the rain drenching them soggy and the wind leaving fragments of faded, barely tinted plastic all around. What to do with these spent flowers is sometimes problematic. The floors of woodlots adjacent to cemeteries are often littered with floral bits and pieces (and occasionally large piles), despite signs asking people not to throw old flowers into the woods. Some sites provide bins for discarding flowers that are no longer decorative. A few display rules regarding their disposal. These signs are often hand-made and generally seem ignored.

As one wanders through cemetery after cemetery, noting tombstones, gravesite displays, markers for children, emblems of religious belief, and the garish brilliance of plastic floral displays (as well as their dreary, worn out remains), it’s easy to forget that each person in each cemetery was a singular individual. Each had his or her unique identity and lived a life distinct from anyone else’s. These are qualities that cannot be embodied by words carved in stone, numbers testifying to life spans, tombstone artwork, or items left in remembrance. The closest analogs to such individuality may be the scientific facts of fingerprints or DNA, but faces usually suffice for most of us. One doesn’t see many faces in cemeteries, but there are some. A few are on tombstones, photographs of people dead and gone. Others are of angels.

© Center for the Study of Southern Culture