1The Stanzaic Accumulation of Disaster

In classroom settings, I begin my survey of the blues literary tradition with a sequence entitled “Origins, Definitions, and Myths,” offering students not just my own take on the blues, but relevant writings by Steven C. Tracy, Kalamu ya Salaam, Barry Lee Pearson, and W. C. Handy. Even as I do so, I’m aware that some of my students, like many blues fans and musicians, would rather engage the blues on the level of groove-sponsored bodily pleasure, vocal prowess, instrumental virtuosity, and the epiphenomena of blues fandom: kicking back or boogying down, as it were, with a shot of bourbon in hand. Those, too, are valid ways of apprehending the blues, but critical reflection in an academic context demands that we bracket such participatory pleasures, holding them in tension with a willingness to formally explore the inner workings of the form.

Distilled to its essence, my schema goes like this: blues conditions lead to blues feelings, which find issue in blues music (or blues expressiveness more broadly); the conditions, feelings, and music are encompassed by the blues ethos. Even as we break the blues down into component parts, it is important to acknowledge that all four things—conditions, feelings, music, and ethos—are interpenetrant, meaning they are bound up with each other; they are in dialogue; they work in concert. This is one reason why some people look askance at the sort of analytic moves I am making here: they think of the blues as a continuum in which the music, the feelings, the problems being sung about, and the swaggering (or stoic, or hyper-emotive) persona all flow together. They are not wrong to view the blues that way, but that flow-zone is not the final word. We can dig a little deeper and figure out how the blues do their work.

What the blues expresses, of course, is not just feelings: most blues songs, from “Back Water Blues” and “Sweet Home Chicago” to “Sweet Rough Man” and “Mean Old World,” spend considerable lyric energy representing the conditions—the challenging, despair-and/or-euphoria-inducing situations—that give rise to the feelings. Blues songs often state a problem, let it simmer and intensify, then pose a provisional solution. What generates the solution, as often as not, is the blues ethos: the blues philosophy of life. The blues ethos, as a concept, is multipronged, not unitary. It is a handful of attitudes and strategies for coping gracefully with the worst that life can throw at you. One definition of the blues ethos, and a brilliant one, is offered in the form of a rhetorical question by African American philosopher and social critic Cornell West: “How do you generate an elegance of earned self-togetherness, so that you have a stick-to-it-ness in the face of the catastrophic and the calamitous and the horrendous and the scandalous and the monstrous?”1

Blues poetry finds surprising ways of staging all four elements of my schema—as in “Bad Luck Card” by Langston Hughes:

Cause you don’t love me

Is awful, awful hard.

Gypsy done showed me

My bad luck card.

There ain’t no good left

In this world for me.

Gypsy done tole me—

Unlucky as can be.

I don’t know what

Po’ weary me can do.

Gypsy says I’d kill my self

If I was you.2

The blues condition undergirding the poem is failed or unrequited love: the “you” in the first line who does not, or no longer continues to, love the poem’s speaker. Superadded to that condition and reinforcing it in the speaker’s mind is a more general condition of unluckiness, one affirmed by the gypsy’s fortune telling. Blues feelings here begin as the speaker’s desolation in the face of doomed love, but they quickly enlarge themselves, in the second stanza, into a comprehensive sense of doom, in which the speaker, convinced that all “good” has vanished from the world, seems headed toward suicide. Blues expressiveness shows up in a range of ways, including the black vernacular language deployed by the speaker and the “autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically” evoked in Ralph Ellison’s famous definition.3 Repetitions—the stanzaic accumulation of disaster through “me” and the gypsy—are one formal means through which that chronicle does its work. Finally, the blues ethos is visible here not as West’s elegance of self-togetherness, but rather as the poem’s unexpected last couplet: a summary insult to the speaker’s collapsing ego, one that wards off pain by precipitating harsh laughter. What might at first seem like egregious tactlessness on the gypsy’s part can also be seen as a healer’s shrewd attempt, with a wink and a nod, to puncture the speaker’s maudlin and maladaptive response to bad news. Or perhaps the speaker, telling us his story of woe, is extrapolating from the fortune-telling situation, inventing the gypsy’s final comment in an act of creative exaggeration. We cannot know, but the poem offers us a moment of enlightenment regardless; it lifts our spirits with a chuckle by conjuring up a blues figure who says, in effect, “You think you’ve got troubles? Ha!”

The fact that Hughes’s poem consists of three stanzas might remind us of the debt that blues poetry owes to the tripartite, AAB structure that is blues music’s best-known and most ubiquitous formal characteristic. The emergence of blues literature, in fact, is partly the story of how poets like Hughes and Sterling Brown, novelists like Claude McKay, songwriters like W. C. Handy, and folklorists like Howard Odum rendered the “humble blues lyric” (Ellison’s term) on the written page, translating and transforming it in the process. It would behoove any blues scholar in training to become intimately familiar with the AAB verse form. That form happens to be lingua franca at blues jams around the world, but it is also one of African American literature’s signal contributions to American literature.

One of the things that characterizes early blues music is an unusual amount of repetition and a distinctive song form. American music in the first two decades of the twentieth century, whether the popular music of Tin Pan Alley or the religious music of the mainline black churches, gravitated towards a sixteen-bar verse format, with popular music often adding a sixteen-bar bridge. Blues, by contrast, offered itself in a three-line, twelve-bar format, and without a bridge—except for Handy’s “St. Louis Blues” (1914), a bridge-bearing blues and the exception that proves the rule. By the mid-1920s, with the advent of recording and especially with the popularity of Blind Lemon Jefferson as a recording star, the AAB verse form had become the accepted norm, as in Jefferson’s “Black Snake Moan” (1926):

I . . . I ain’t got no mama now

I . . . I ain’t got no mama now

She told me late last night, “You don’t need no mama no how”

Mmm, mmm, black snake crawlin’ in my room

Mmm, mmm, black snake crawlin’ in my room

Some pretty mama better come and get this black snake soon.

The AAB verse form, when performed by blues singers, is characterized by a specific sort of repetition-with-variation: the A line, when repeated, is sung over a different chord (the subdominant or IV chord) than the first time around, and singers frequently embroider or “worry” the repeated line in a series of microtonal adjustments, sometimes with lyric elisions or embellishments, that highlight this chord change in subtle but important ways. The difference between the two iterations of the A line is just substantial enough that scholars sometimes refer to the second A line as the A-prime line. The B line, by contrast, is an answering line rather than an echoing line; it almost always rhymes with the A line (although eye-rhymes and non-rhymes occasionally show up), and it sometimes puts an unexpected spin on the theme or emotion or question that was set in motion by the AA pair. In a philosophical sense, it is almost as though what blues song does is try out a statement, one that proposes an emotional or stylistic orientation towards life’s bad news, then reprises or repeats that statement in a way that suggests either a possible variant on the initial stance or, by contrast, an intensification of the initial stance. The B line, in any case, puts a cap on it—or in it—and sends you hurtling into the next verse.

The repetition-with-variation-as-intensification dynamic, so crucial to the language and formal structure of the blues, is one that feels uncannily familiar to those who have suffered on the field of battle that is failed love:

I hate you

I hate you

Take the damn house, and your little dog, too.

The rage that fuels a divorce, rendered this nakedly, is not blues lyricism, but it may have something to teach us about where the music’s magic is sourced: in an urgently felt need to unburden an aching heart, and in the way that a certain kind of immediately repeated complaint may facilitate that unburdening. Repeating their indictments in this way, blues songs harden romantic rage with metaphors that exaggerate to produce bitter laughter. New Orleans blues guitarist Lonnie Johnson ended his seven-year common-law marriage to blues singer Mary Smith in 1932—she had borne him six children during that period—and the acrimony that powered that breakup is audible in “She’s Making Whoopee in Hell Tonight” (1930):

Baby, you’ve been gone all day baby . . . set to make whoopee tonight

You’ve been gone all day . . . set to make whoopee tonight

I’m gonna take my razor and cut your late hours . . . I will be serving you right

The undertaker’s been here and gone, I give him your height and size

Undertaker’s been here and gone, I give him your height and size

You’ll be making whoopee with the devil in hell tomorrow night

You made me love you . . . just got me for your slave

You made me love you . . . just got me for your slave

And from now on you’ll be making whoopee in your lonesome grave

The AAB form is now so ubiquitous as to seem both natural and inevitable, but blues scholars are still not precisely sure where it came from. In his study of Skip James entitled I’d Rather Be the Devil, Stephen Calt argues that the AAB pattern ultimately derives from “Roll Jordan,” a spiritual penned by Charles Wesley (1707–88) that showed up at camp meetings in the 1820s and became an anthem of the second Great Revival, the religious movement that made Christian converts of many black southern slaves.4 In Africa and the Blues, Gerhard Kubik argues for possible Yoruba origins of the AAB stanza, while Harriet Ottenheimer argues for East African origins in the Comoros, an island chain between Mozambique and Madagascar.5 Even as we chase down such distant sourcing, it is worth remembering that early blues songs manifested a range of stanzaic forms. When Handy encountered a “lean, loose-jointed Negro” playing slide guitar with a knife and singing at the Tutwiler, Mississippi, train station in 1903 or 1904, a celebrated moment of first contact evoked in Father of the Blues, the man repeated the line “Goin’ where the Southern cross’ the Dog” three times—an AAA verse, and a form that still raises its head from time to time.6

2Victory Over the Bad Things

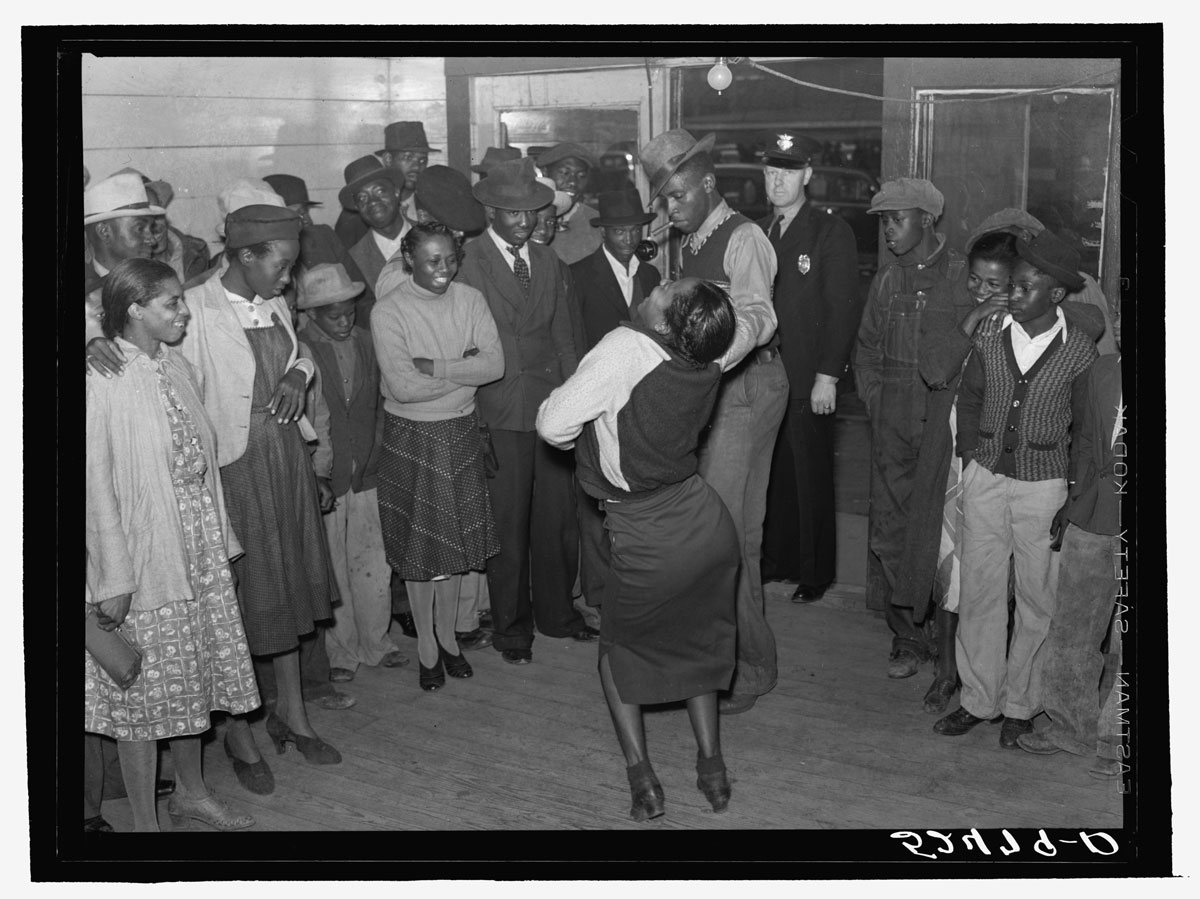

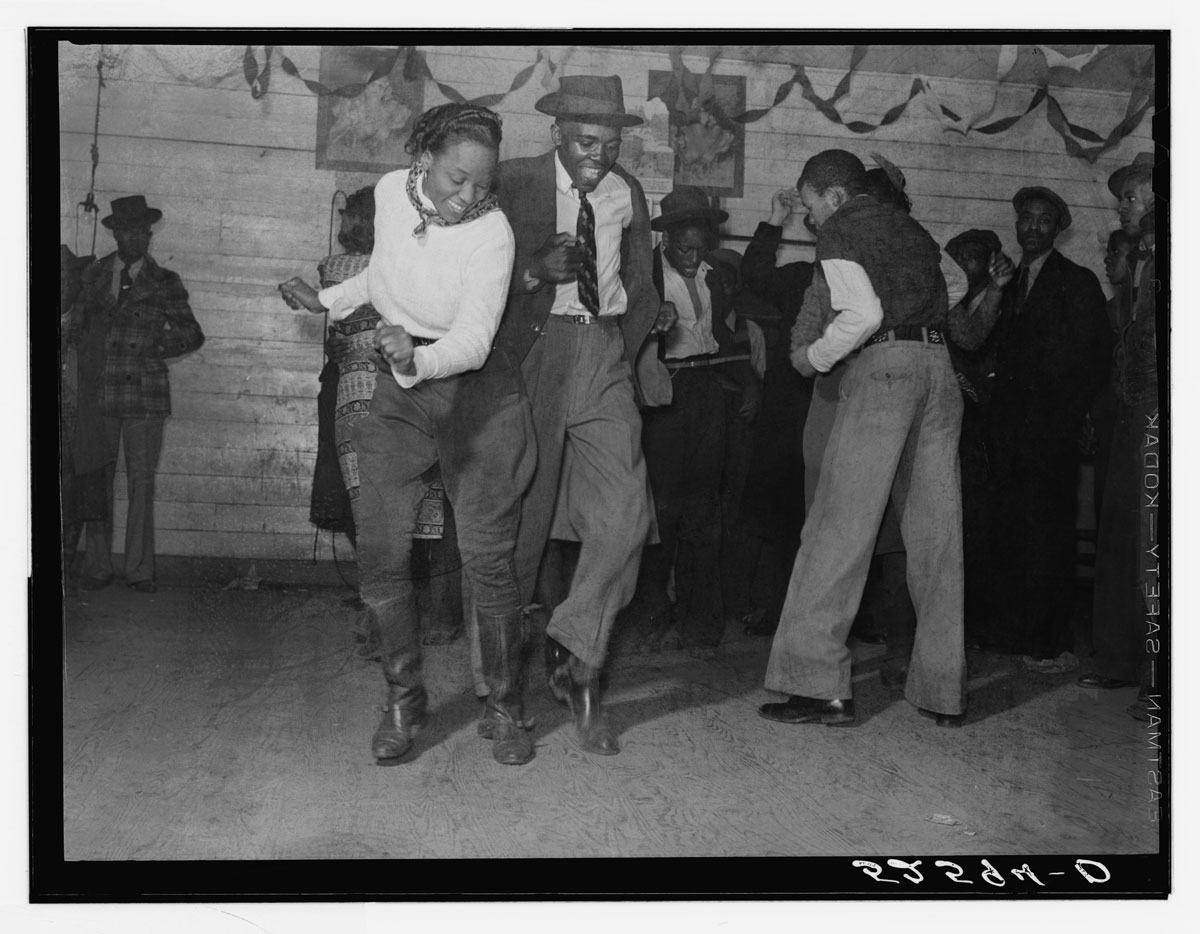

The AAB stanza, so broadly and variously utilized by blues poets and worked into the tissue of prose works, including Handy’s autobiography, is merely one of the formal elements that constitute what I am calling blues expressiveness. A second element is call and response or antiphony: the idea that a given blues text, like a blues performance involving a musician and an audience (or a musician who is his own audience), stages a sort of dialogue or conversation between two voices or ideas or energies. Two things are calling back and forth to each other—reinforcing, versioning, outdoing, and/or signifying on each other. Each is dynamically adjusting itself to the other, so that each response in turn becomes a call that provokes further response. Call and response, as an organizational principle, shows up not just in the blues tradition but in jazz, soul, work songs, slave seculars, and the black religious tradition: church choirs, quartets, anywhere that gospel and the spirituals are sung. It is one of the givens of African American music. Its deep origins arguably lie with the drum-and-dance dialogue that animates many kinds of West African music—an inheritance from slavery, once again—and it has deep philosophical implications for the blues.

Early blues is distinguished from slave music, among other things, by the fact that it is individualistic rather than collective: it features a lone guitarist singing as he picks and strums (Handy’s Tutwiler musician), or a lone female singer backed up by a jazz orchestra. It is not choral music. It is very different in that respect from the raised hymns that one finds in the Gullah churches of coastal Georgia, where a series of voices chime in, double each other, and toss the ball back and forth between a leader and followers. And yet, if one listens closely to the solitary bluesman with his guitar, or the blues queen and her orchestra, one realizes that the call-and-response conversation, the antiphony, has been preserved. In the case of the solitary guitarist, the vocal lines are the calls; the so-called “fills,” little two-bar snatches of slide guitar riffs between the vocal lines, are the responses. If the guitarist is playing duo style with a harmonica player, the harmonica responds to the vocal “calls” in similar fashion. In the case of the blues queen, the orchestra provides not just rhythmic and harmonic background to her vocals, but solo instruments that surface in the spaces between her vocal lines; their instrumental commentary becomes the response to her calls.

Call and response knits the blues community together. In philosophical terms, call and response says, “Yes, you are suffering and I am suffering. We are suffering. And you hear my suffering, and respond to it, as I hear your suffering and respond to it. We get the feeling out, we give it a ritual public airing. We give it form—a powerful, elegant, shapely expressive form. And in so doing, we earn ourselves a victory over the bad things that have happened to us. The music we make together is more powerful than the thing they’re trying to make of us.” This philosophical victory takes a slightly different shape when a blues queen like Bessie Smith is fronting her orchestra before a packed house than it takes when Belton Sutherland, a little-known Mississippi guitarist, is communing with his guitar alone at home, but the underlying principle is the same. Rather than one person suffering quietly and alone, there’s a conversation going on, one that manifests dialectical energy and human creativity. A deep cultural form tracing back to Africa is being worked with, animated, put in service. I am dealing with the loneliness that I feel by creating a call and response dialogue between me and my guitar, or my orchestra. If I’ve got an audience, the dialogue I’m staging may in turn provoke a second-order conversation in which you, my congregation, respond to what I’m offering you with your own running commentary, your shouts of approval and affirmation. Then, as they say, we are really cooking with gas.

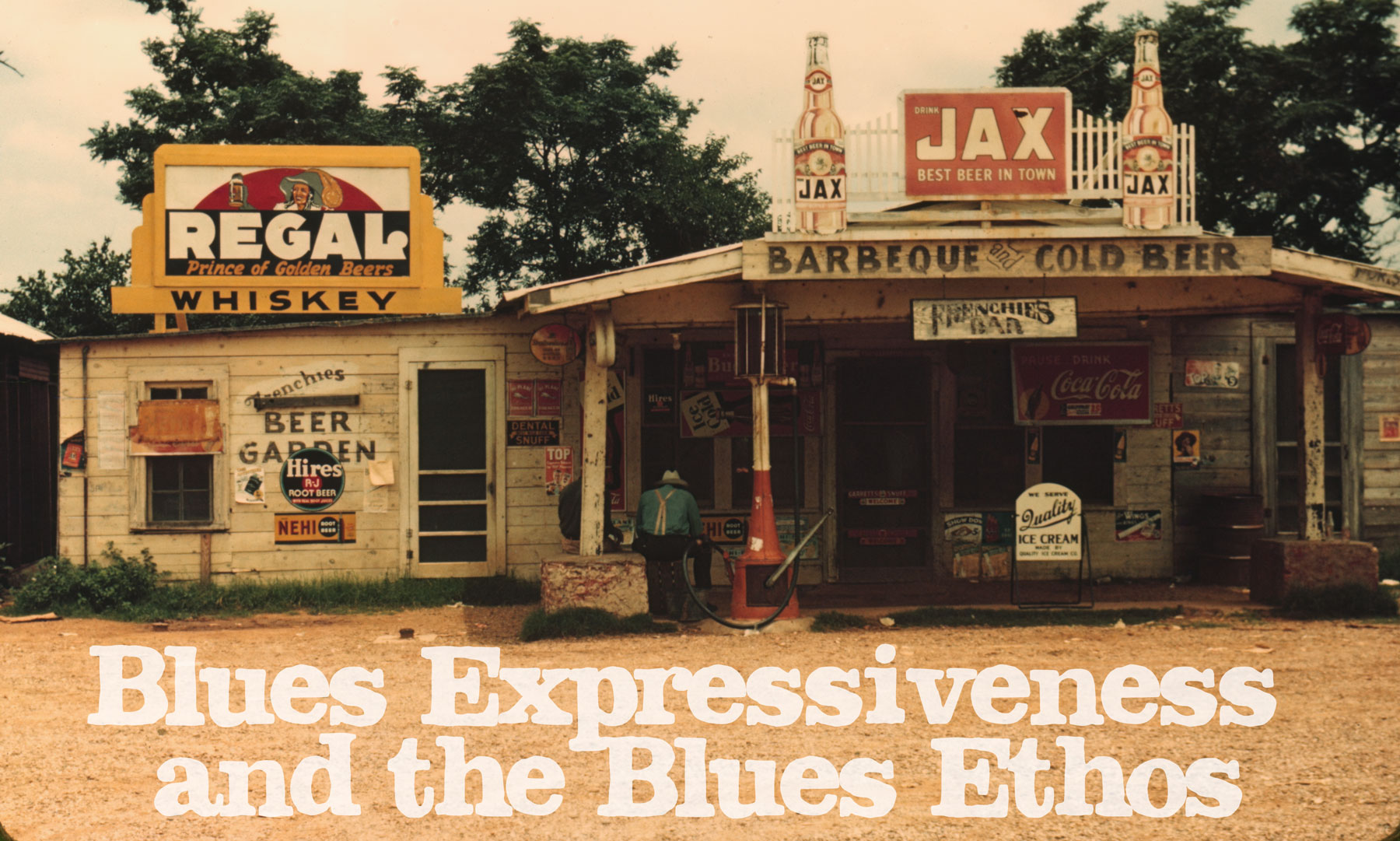

Call and response procedure, in short, bodies forth a core value of the blues: the idea that pain needs to be externalized and shared rather than suffered alone, along with the idea that there is something ennobling and healing about this process. As with many elements of the blues, this value first takes shape during the slavery era. In Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (1982), historian Orlando Patterson explores the way in which slavery was, in fact, a kind of comprehensive social death, one that left the enslaved person not just powerless and without honor, but alienated from his natal rights—i.e., shorn of all familial connections and ancestral claims, including his own name.7 The Dred Scott decision (1857) affirmed social death when it argued that all blacks were “beings of an inferior order” and, as such, “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The African American response to this situation in the antebellum South was the so-called “invisible institution” of the black church: hush harbor meetings out of sight and hearing of whites within which wounded spirits could be salved by a shared unburdening that was sustained by mutual recognition and respect. In the decades after Emancipation, black churches were a visible and proliferating source of pride for the communities they served. Titles, honorifics, and a high sense of ritual purpose helped heal the comprehensive disrespect that enforced social death. During those same post-Emancipation decades, as Katrina Hazzard-Gordon reminds us in her study Jookin’, juke joints were beginning to emerge across the South, offering similar kind of healing to the blues communities that circulated through and within them.8 In The Spirituals and the Blues (1972), black theologian James Cone calls the blues “a secular spiritual” as a way of getting at this dynamic.9 The juke joint is the place where performers and their congregations stage a sacred ritual of unburdening. The most skilled and powerful performers, those who fulfill the call and response mission in the most cathartic way, literally create names for themselves in this way.

Along with AAB structure and call-and-response procedure, we might add a third item to our survey of blues expressiveness: vocalizations. What makes blues music instantly identifiable—not the lyrics, but the music itself—is not just the twelve-bar harmonic structure, or the instruments (slide guitar, harmonica), or even the microtonality of the so-called “blues scale” that finds useful pitches between the white and black keys of the piano. It is also, and more specifically, the way in which blues players—especially guitar and harmonica, but also saxes, trumpets, and other brass—model elements of their playing on what blues singers do. They make their instruments yelp, hoot, curse, scream, and cry. Talk, in a word. Salty Holmes’s “I Want My Mama” (1950) and Sonny Terry’s “Talking Harmonica Blues” (1959) offer vivid examples of harmonica players doing this; Albert Collins and Luther Allison were masters of the talking-guitar technique, sliding their fingers up and down the strings to create the illusion of utterances like “No, I won’t!” or “Ohhh, noooo!” In “Luther’s Blues” (1974), Allison stages an agitated dialogue between himself and his woman—the guitar “talks” her part—so that call-and-response procedure and vocalizations work synergistically, but the idea of talking through an instrument has a deeper meaning, I believe, than merely signifying on human speech.

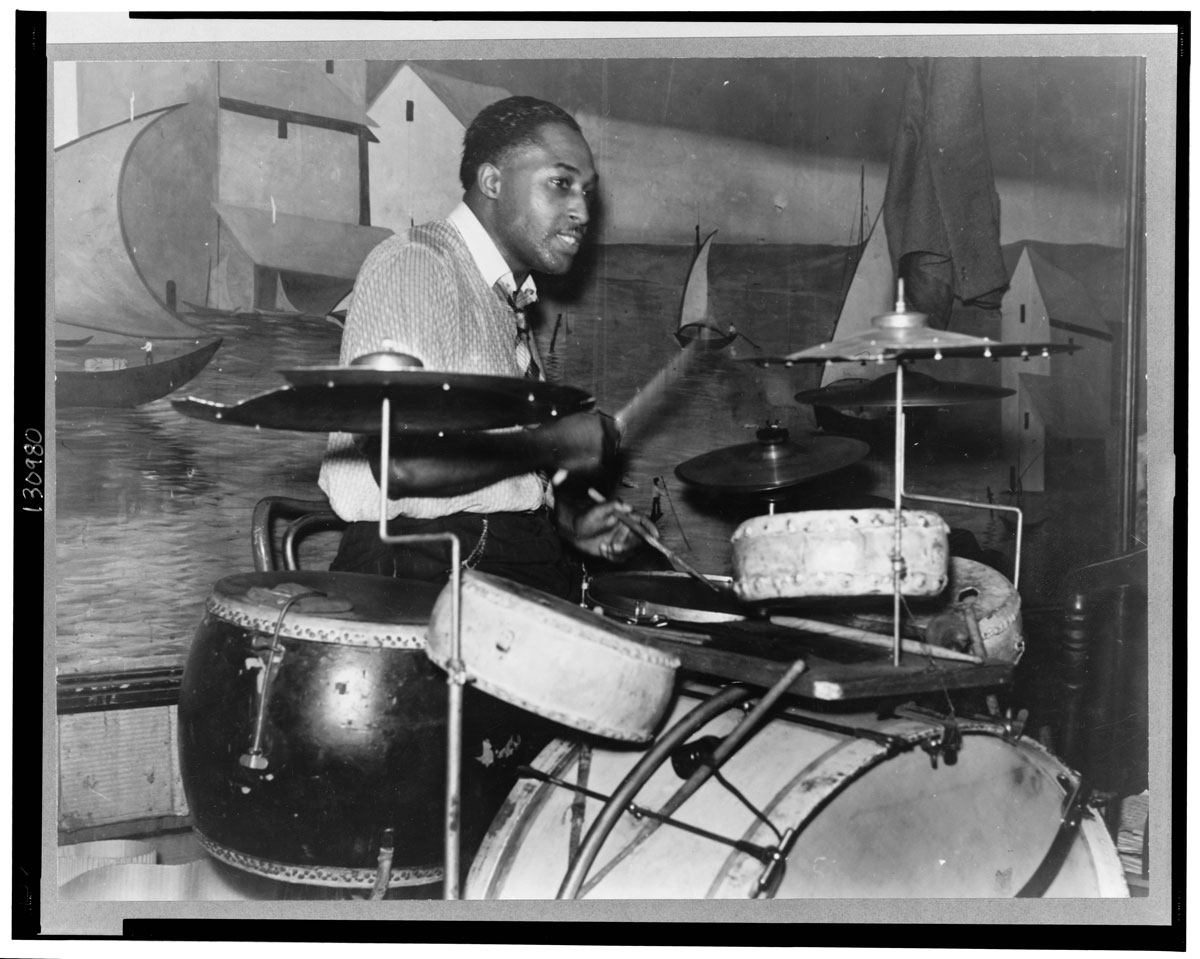

The talking drums were a significant element of musical life in the part of West Africa preyed upon by the Atlantic slave trade. My intuition tells me that the deep historical origins of the virtuosic vocalizations of musicians like Holmes, Terry, Collins, and Allison, lie in the pitch-tone language being instrumentally mimicked by the talking drum of Africa. That language, and that conception of drumming, was a part of the cultural material that slavery ended up depositing in the southern United States. After drums were banned in South Carolina and then across the South in the aftermath of the Stono Rebellion of 1741—a slave rebellion orchestrated, whites insisted, by talking drums—drum language and rhythmic fluency were preserved for more than a century as the slapping-the-body practice known as patting juba. Black people in the South found ways of keeping the drum alive, despite white proscriptions. Drums flourished in the post-Emancipation world of black minstrelsy, brass bands, and jazz, of course, but the blues was one of the places where the broader drum-function created by the earlier ban remained in play: in Charley Patton’s habit of beating rhythms on the wooden body of his guitar, in the way Bukka White snaps and pops his bass strings, in the heavy front-porch foot of Belton Sutherland and other solo guitarists looking to entertain a dance crowd, in phrases like “[S]pank that ole pe-anner” shouted by Zora Neale Hurston’s Florida juke joint informants in Mules and Men.10

3Signifying, Subterfuge, and Sexuality

So vocalizations are an important element of blues expressiveness, along with AAB structure and call-and-response procedure. A fourth aspect of blues expressiveness is something I will call blues idiomatic language. By this I mean the rich linguistic stew in which members of the blues subculture—musicians, audiences, and assorted hangers-on—conduct their daily lives, on and off the bandstand. There are two superb books about this subject: Debra DeSalvo’s The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu (2006) and Stephen Calt’s Barrelhouse Words: A Blues Dialect Dictionary (2009). African retentions show up in blues language, as DeSalvo notes—the words “hip” and “cat” both have Wolof origins—but even more important is the “freewheeling all-American lingo” of the underground economy that helped folks on the receiving end of Jim Crow survive and occasionally prosper. “Blues artists,” she writes, “—looking to steal from the best, like all songwriters—nicked words and phrases from the numbers runners, hookers, drag queens, thieves, junkies, pimps, moonshiners, hoodoo doctors, dealers, rounders, and con artists who made up the street set.”11

The language of blues expressiveness is a rowdy, street-level American vernacular rooted in the language of the black southern folk. Anybody who has read Hurston’s Mules and Men and Their Eyes Were Watching God, anybody familiar with her evocations of Sop de Bottom, Big Sweet, and Tea Cake, knows how much boastful, playful, threatening, self-annunciating energy the language of blues people contains. The blues underworld that generated that language was, among other things, a place where flesh—sexual attractions, sexual potency—was an important currency. The prominence of sexuality within blues discourse is what academics call overdetermined: it has multiple sources, not one source. The red-light-district environs within which early blues performances often took place were a breeding ground for such language; the harsh, labor-centered daylight lives of black blues audience members made bodily pleasures an enticing theme. Commercial considerations, too, incentivized titillating blues songs. Once Tin Pan alley jumped on the blues bandwagon in the 1920s, the “clean and racy . . . folk speech” of early blues singers, according to Harlem Renaissance spokesman Alain Locke, was transformed into “the mawkish sentimentality and concocted lascivity of the contemporary cabaret songs and dances”12:

The one is primitively erotic; the other, decadently neurotic. Gradually the Negro singers and musicians succumbed to the vogue of the artificial and decadent variety of song, music, dance which their folk-stuff started, and spawned a plague, profitable but profligate, that has done more moral harm than artistic good.

The distinction between good-sexy (“racy,” folk-originated) and bad-sexy (“decadent,” commercial, modern) blues songs is a difficult to uphold. In 1910, a decade before Tin Pan Alley began to pay much attention the blues, pioneering folklorist and Howard Odum was recoiling with moral horror at the prominence of sex in the “great mass of vulgar and indecent songs” that he had encountered in his travels among working-class African Americans in rural north Mississippi:

Often such songs are in the majority, and they are generally favorites among the negroes. . . . [These] songs tell of every phase of immorality and filth; they represent the superlative of the repulsive. . . . The prevailing theme of this class of songs is that of sexual relations, and there is no restraint in its expression. In comparison with similar songs of other peoples that have been preserved, those of the Negro stand out in a class of their own. They are sung at the dance and other mixed gatherings. They are sung by groups of boys and girls, of men and women, and they are sung by individuals who revel in their suggestiveness. Here the vivid imagination of the Negro makes his constant thought a putrid bed of rottenness and intensifies his already depraved nature. Openly descriptive of the grossest immorality and susceptible of unspeakable thoughts and actions, rotten with filth, they are yet sung to the time-honored melodies.13

We are savvy enough, I trust, to recognize Odum’s moral revulsion as the fusty, racially retrograde Puritanism of a man from the pre–Great War era, a cultural sensibility that H. L. Mencken and the Jazz Age managed successfully to rout. But of course recorded and commercialized blues song, along with the animal-themed dance crazes that accompanied them—the Turkey Trot, Bunny Hug, and Grizzly Bear—was itself a key instrument for effecting this culture-wide loosening-up. And one familiar rhetorical move through which the rout was conducted is, as it happens, still alive and well in our own day: signifying.

Signifying plays a key role within African American expressive culture; it is as much a church thing as a blues thing, and it is actually a range of related things, not one thing. At heart, signifying is saying one thing but meaning another, where the thing that is said often takes on a figural energy of its own, even as the interest and importance of the “meant” thing, by being partly or wholly masked, is highlighted for an audience hip enough to get the word-play. Signifying, in folklorist Roger Abrahams’s words, is a “style-focused message” in which “styling . . . is foregrounded by the devices of making a point by indirection and wit.” In a church context, signifying shows up in the spirituals, where a phrase like “crossing over” may gesture towards a range of real-world referents, from fleeing slavery’s clutches across the Mason-Dixon line to any yearned-for political development, such as the election of President Obama, that represents a prophetic realization of black freedom-dreams. In a blues context, the most familiar form of signifying is sex-talk: finding a thousand and one ways of boasting, preening, and configuring a sexual come-on, or complaining about a lover’s faithlessness.

Sexual signifying is a foundational element of blues expressiveness. The most familiar lyric of this sort might be, “If you don’t want my peaches . . . please don’t shake my tree.” That line first enters the tradition, surprisingly, in an unpublished 1914 composition by Irving Berlin, the dean of Tin Pan Alley, but Berlin had almost certainly taken it—as an overheard phrase—from black oral tradition, and it shows up, along with its many variants, in songs by everybody from Bessie and Trixie Smith to Elmore James and the Mississippi Sheiks. In “Peach Orchard Mama” (1929), Blind Lemon Jefferson sings of his errant lover’s fondness for robbing the cradle: “you swore nobody’d pick your fruit but me / I found three kid-men shaking down your peaches free.” Sexual signifying in blues lyrics achieves several things. If we remember, as theater scholar Paige McGinley urges us to, that the great African American blues queens used every expressive technique at their disposal to dramatize their songs on the stage, then we can appreciate the way in which such lyrics open up an enlivening participatory conversation between the statuesque female performer, gesturing at her own curves, and her appreciative audience.14 Men appreciate the curves; women appreciate the ethical point, which in our own vernacular might be voiced as: Don’t play me. If you want all this—the glory of my womanhood—then don’t just arouse my interest long enough to steal my sex and hurt my feelings. Follow through. Show me your love and make me your woman.

Sexual signifying offers blues song a way of creating pleasure through heavily freighted indirection: plays on words that gesture forcefully at sexualized bodies and the sex acts they engage in without actually using the four-letter Anglo Saxon equivalents. In “Empty Bed Blues” (1928), composed by J. C. Johnson, Bessie Smith sings of being deserted by a new lover, celebrating with vivid suggestiveness his hip-powered prowess and endurance:

Bought me a coffee grinder, got the best one I could find

Bought me a coffee grinder, got the best one I could find

So he could grind my coffee cause he has a new grind.

He’s a deep sea diver with a stroke that can’t go wrong

He’s a deep sea diver with a stroke that can’t go wrong

He can touch the bottom and his wind holds out so long.

The origins of signifying lie in the antebellum South, when enslaved African Americans had a pressing need to communicate sensitive information with each other in public spaces on the plantation—an impending escape attempt, for example—in a way that evaded detection by the master. Sexuality wasn’t part of the signifying equation at that point, but it takes center stage in the blues during the post-Emancipation period because, according to Angela Y. Davis (Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, 1998), sexuality, along with travel, “was one of the most tangible domains in which emancipation was acted upon and through which its meanings were expressed.”15 In other words, sexual signifying plays such a central role in blues expressiveness because the right to flirt with, chase, romance, couple with, and ravish the lover (or lovers) of one’s choosing was a key way in which freeborn black southerners lived out, knew, their freedom. No longer did the slavemaster have the right to select your mate and keep you down on the farm. It’s all about me and you, baby: the crawling kingsnake and the fine brown hen. The blues lyric tradition signifies endlessly on this point.

4A Brutally Honest Recognition of Reality

Thus far I have been talking about a range of topics that can be subsumed within the category of blues expressiveness‑—the AAB verse form, call and response, vocalizations, blues idiomatic language, and signifying. The analytic proposition I’m exploring, you may remember, goes like this: blues conditions lead to blues feelings, which find issue in blues music (or blues expressiveness more broadly); the conditions, feelings, and music are encompassed by the blues ethos. I’d like to turn now to that fourth global concept. What is the blues ethos and why does it matter?

Like blues expressiveness, the blues ethos is several related things, not just one thing. When most people offer definitions of the blues, they tend to neglect the blues ethos. It is easier to invoke the distinctive three-line stanzas, or major/minor tonalities, or the multiple oppressions of black life in the rural South, and say “That is the blues.” Yet the blues ethos—an attitudinal orientation towards experience, a sustaining philosophy of life—may be the most important ingredient of all. I’d like to use my own experience as an example.

My first exposure to the blues ethos came long before I had encountered the concept by name. In 1986, shortly after I began playing harmonica on the streets of Harlem with a Mississippi-born guitarist known as Mr. Satan, one of his sidewalk fans told me that his real name was Sterling Magee. When I expressed curiosity about the name-change, a story soon emerged. I was told he’d had a very beautiful wife—curvy, sexy—and she’d gotten cancer. He stayed right by her bedside, nursing her. When she died, he fell off the deep end. He dragged himself back home to Mississippi, drunk and inconsolable; months later, when he returned to Harlem, he was calling himself by the new name and demanding that everybody else do the same. That was five years before I had come along. The Mr. Satan I knew was the opposite of despairing: he was a ring-tailed roarer animated by phenomenal talent and energy, joyous and irrepressible. We would talk about women from time to time, as musicians often do, and I’d confess my own fury at the live-in girlfriend who had cuckolded and deserted me a couple of years earlier. He’d respond by decrying the worthless temptation represented by women and their “smelly little behinds.” When I would speak of my lingering pain, he’d vigorously push back. “Hell,” he would say with a harsh laugh, “I had so many women die on me, I was thinking of opening a funeral parlor.” How could I not chuckle along with him? How—knowing what I knew of his own encounter not just with romantic tragedy but with death—could I not put aside my self-pity and get back to the business of living?

That was my baptism into the blues ethos: that harsh laugh, and the exaggeration that accompanied it, transforming pain into life force. I had not yet encountered the writings of Albert Murray or Kalamu ya Salaam, but the experience helped me appreciate their insights when I finally did. “[W]hat is ultimately at stake,” writes Murray of black blues life in Stomping the Blues, “is morale, which is to say the will to persevere, the disposition to persist and perhaps prevail; and what must be avoided by all means is a failure of nerve.”16 Stoic persistence, a refusal to give up, lies at the core of the blues ethos. And a certain kind of reality-based, fantasy-assisted humor, according to Salaam, is a tool with which blues people have managed to enable such persistence. “[R]ather than an escape from reality,” he argues in “The Blues Aesthetic,”

when we fantasize, it is based on a brutally honest recognition of reality, a reality albeit clothed in metaphorical grace. This grace includes, but is not overcome by, a profound recognition of the economic inequality and political racism of America. Thus, we laugh loud and heartily when every rational expectation suggests we should be crying in despair. The combination of exaggeration and conscious recognition of the brutal facts of life is the basis for the humor of blues people, which is real black humor.17

Mr. Satan’s joke about dead wives and funeral parlors, exaggerating and ridiculing heartbreak in order to swat it away, epitomizes the blues ethos. There’s a spiritual wisdom in it. How should you deal with bad news? Black southern blues people, given the economic and social challenges arrayed against them, figured out pretty quickly that wallowing in despair—whining—just wasn’t an effective long-term strategy. They complain, to be sure, but they do so in a context that facilitates a spirit of creative resistance. The blues ethos acknowledges the power generated when emotional pain is annealed with a self-mockery that wards off descent into outright, immobilizing depression. The sadness of the blues, according to Langston Hughes, “is not softened with tears but hardened with laughter,” and that word “hardened” is important. Spiritual toughness is part of the blues ethos.18 Never, ever, ever, ever give up. Even when you give up, do so only as long as you need to. Then pick yourself up and get cracking.

Don’t, in other words, spend any more time in that state of given-up-ness than you need to. To do so bespeaks spiritual immaturity: an unwise insistence on reifying the miseries of the present moment. To say, like a pouting child, “Because I am down now, I will always be down,” is to blind oneself to the possibilities for escape and future triumph that are always present, at least potentially, in even the most unpromising of circumstances. This is the wisdom contained in the blues standard “Trouble in Mind”:

Trouble in mind . . . babe I’m blue

But I won’t be blue always

Because the sun’s gonna shine in

. . . my back door someday.

“Trouble in Mind” is sung from a condition of deep sadness, but it demands that we reframe that sadness in a way that looks ahead, with prophetic wisdom, to the possibility of a better life. The long arc of black history, bringing African slaves to Jamestown in 1619 and an African American President to the White House in 2008, energizes both poles of the dialectic. When all else fails, insists the blues ethos, look down that road. Take the long view. Stay loose. Keep things moving. Give your luck a chance to change.

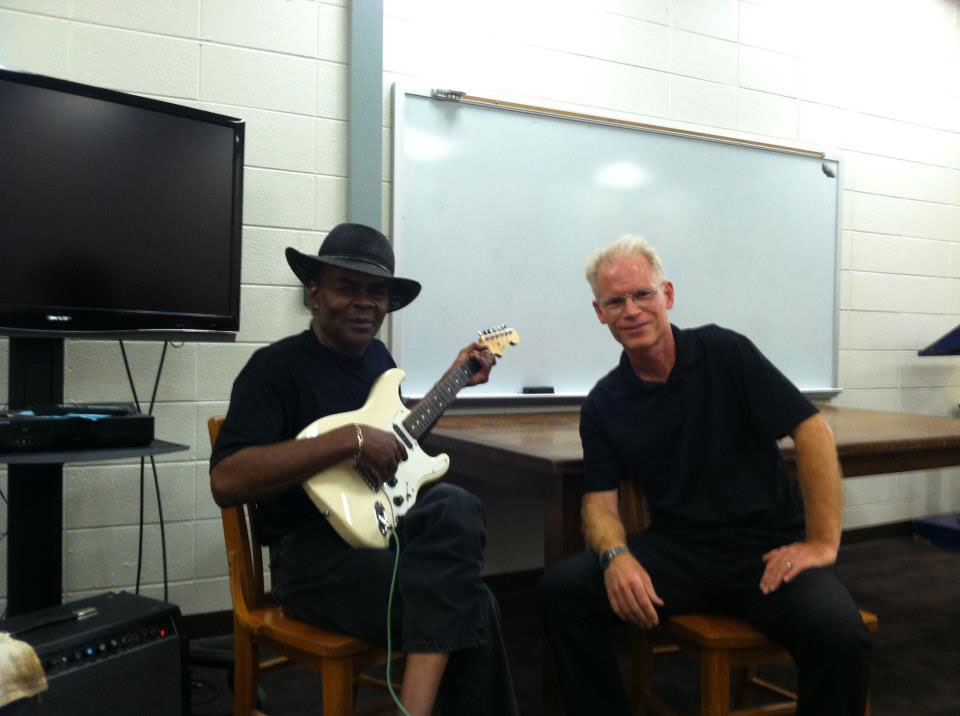

When Bill “Howl-n-Madd” Perry, a Lafayette County bluesman, visited my undergraduate blues class at the University of Mississippi in 2012, he had to be helped to his seat by his daughter, Shy, who travels and plays keyboards with him. Several months earlier, Bill had had a minor stroke and lost ninety percent of his vision. Yet his spirits were undimmed, even ebullient. When I described the blues ethos, a concept we’d been working with, and asked him what he thought, he smiled and said, “I’ll tell you a story about that.”

Many years ago, he said, he’d played guitar in Little Richard’s band. They were based in Chicago—he’d migrated from Mississippi to Chicago as a young man—but they traveled a lot, and on this particular trip they were in Los Angeles. That’s where Little Richard fired him. “When I came down in the morning from my hotel room,” he said, “they were gone.”

“What do you . . . that’s how they fired you?” I asked.

“They were gone.” He chuckled. “They were just gone.”

“What did you do?”

“Well,” he said slowly, leaning back in his chair, “I didn’t feel too good.”

The class laughed.

“But what was your next step?”

“Well, the band was gone, and I had a dollar in my pocket.”

“What did you do?”

“I spent ninety cents on some breakfast.”

More laughter. He was grinning now.

“What did you do after that?”

“I got out on the road and started walking with my guitar. And somebody came along who knew me—we’d been in town for a few days and somebody drove by and they knew me, and they picked me up and brought me to their place. I stayed there for a week, played a few pickup gigs, and made enough money to get back to Chicago.”

There’s a kind of wisdom here that deserves our attention. Bill could have retreated his hotel room in shock. He could have drowned in his own fury and self-pity, flailing helplessly. But his response to the sudden appearance of blues conditions—loss of a job and housing, incipient poverty, sudden stranding a long way from home—was to remain loose and forward-looking rather than giving in to shame, fear, and despair. He got out on the road and started walking. He gave the world a chance to rectify the situation. And it did. That sort of quick reversal rarely happens, of course. But it is guaranteed not to happen unless you put yourself in a position where it can happen. The blues ethos knows all this. Those who embody the blues ethos have the wisdom and resilience, the strength of character, to respond to bad luck by setting transformative possibilities in motion.

5You'll Live Through It

I came to a deeper understanding of the blues ethos after Mr. Satan and I left the streets of Harlem in the early 1990s and began to tour, putting in some serious road-miles. He was a feelingful man, but an unsentimental one, disinclined to coddle or be coddled. He’d spent a fair bit of time picking cotton in the Mississippi Delta as a boy; he was a hard worker, not a complainer, and he expected the same from me. One night when I picked him up at his apartment for a downtown gig, he had a bloody bandage wrapped around his hand. “What happened?” I asked. “I cut myself on a piece of wood,” he said, making a sour face. “I’ll live through it.” The cut turned out to be a deep gash in one of the heavily callused fingers on his fretting hand. Any other guitar player would have canceled the gig. That wasn’t his way. He played the five-hour gig, wincing occasionally but never complaining. Make the gig: that was his philosophy. The blues ethos in action.

“You’ll live through it” was Mr. Satan’s all-purpose rejoinder whenever I’d complain about something. The phrase began to make sense when I thought about the sorts of challenges he’d encountered growing up black and male in rural Mississippi in the 1930s and 1940s. Living through it, whatever “it” was, couldn’t be taken for granted—which was precisely why he’d evolved that saying. It put things in perspective. It reframed them in a useful way. It didn’t say, “Things are easy.” It said, “They’re bearable, compared with the worst-case scenario, and they’ll get easier by and by.” When disasters threatened out on the road, or even just modest inconveniences, Mr. Satan was ready. “We’ll live through it.” And we always did.

Several summers ago I drew on the blues ethos in a way that showed me the practical efficacy of the concept. With the help of some friends, I had organized a weeklong one-man-band tour that was going to take me from Oxford, Mississippi, up through Columbia, Missouri, to Mankato and St. Paul, Minnesota, back through Chicago, and then home. Two club dates, a festival, and a guest slot in a blues harmonica workshop. Decent money and some professional recognition on my own terms, not as part of a duo. Two thousand miles, there and back.

The night before I was supposed to take off, I came down with a fever. The road is hard enough when you’re well, but a solo tour when you’re sick is hard. It’s not something I wanted to do. I woke the next morning—I hadn’t yet packed the car—and the fever was still there. Not only was the car unpacked, but when I hobbled outside to do a quick walk-around, I discovered that the worn-out rear tires I’d been nursing for months had suddenly developed the sort of bubbled sidewalls that precedes a blow out. I sat there on the sofa at 7:30 in the morning, thoroughly demoralized, with the entire tour hanging on a thin string. If I stayed put for a few hours, giving the fever a chance to subside, I’d miss that evening’s gig in Columbia, 450 miles away. If I blew off the Columbia gig and left for Mankato the next morning, I’d have 900 miles to drive in one day. That wouldn’t happen and the tour would collapse. I thought about the young harp guys who had helped set up those two gigs, each of whom was opening for me, and asked myself whether my fever could justify disappointing them.

Then I thought back, suddenly, to a tour that Mr. Satan and I had taken in 1997—a trip to Australia, our first. I’d developed a big, ugly fever blister on the way over, during the fourteen-hour flight from Los Angeles. Once we landed, we’d be playing two shows a day for seven straight days, starting the day we arrived. When I showed the blister to Sterling, frustrated and depressed, he just shrugged and said, “You’ll live through it.” Then he added, “We’re playing those gigs, mister.” And we did, and I did. It wasn’t pretty—I’d wiped some blood off my mouth for the first couple of nights—but the pain was bearable. I’d settled in after a couple of days, I’d drunk a fair bit of booze to smooth off the rough edges, and we’d made the gig. That’s what blues players do. You want to play this music? Toughen up.

I sat on the sofa, thinking about all this. Then, for no good reason, something inside me reached down and anchored itself in a layer of cussedness lurking just below the feverish negativity. “Here’s what you’re going to do,” I said to myself, as though I were lecturing somebody else. “You’re going to take a shower and load up the car, you’re going to drive over to Batesville and buy some tires, and you’re going to head north. If the fever gets worse and you can’t make Columbia, you can pull off the road and crash for the night, and at least you’ll know you tried. If you have to, you can cancel the rest of the tour first thing tomorrow and drive home. But if you don’t leave home now, if you don’t take that first step, bad as you feel, you’ll blow the whole tour before it starts. You’re not going to do that. Too many people worked too hard to let that happen.”

Thinking about others, reorienting myself toward the blues community, was a part of the cure. But sheer toughness of spirit, a decision to move forward anyway, regardless of how I felt, was also required. As it turned out, everything worked out. I bought the new tires and rolled north; the fever gradually subsided. By the time I hung a left past St. Louis, late that afternoon, I was fine. The weather was hot as hell—over a hundred degrees—but I couldn’t complain. The tour went off as planned.

Buddhists talk about the difference between pain and suffering. Pain, they teach, is an inevitable part of embodied life. Suffering, however, is a mental construct—all the feelings of disappointment, negativity, apprehension, and despair with which we routinely surround, and heighten, pain. Blues songs traffic in suffering. Ralph Ellison memorably called the blues “an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.”19 But the blues ethos, the philosophy of life that sustains blues musicians and other blues people, prefers to acknowledge pain in order to evade suffering, whenever possible. See it, say it, sing it, share it. Get it out, by all means. Don’t deny the pain, or hide from it. But don’t wallow in it, either. Use harsh humor—near-tragic, near-comic–to kick it away. Use stoic persistence to get past it. With luck, you’ll leave it in your rearview mirror. Or not. But it’s worth a try.