Since Robert Johnson’s death in 1938, he has become a cultural icon and has been referred to as the “King of the Delta Blues.”1 During his brief life and career, he traveled and performed throughout the Mississippi and Arkansas Deltas, and as his fame spread he began performing in St. Louis, Memphis, Detroit, Chicago, and New York.2 As a “walking bluesman,” Johnson sometimes traveled from town to town by train, hitched a ride, or even rode on the back of a farm tractor. When he arrived at his new destination, he performed on street corners, in front of barbershops and restaurants, town squares, or in local juke joints.3 According to a Johnson biographer, he chose the life of a walking blues musician because it was preferable to the backbreaking and monotonous work that sharecropping entailed.4 In doing so, Johnson gained the admiration of Delta blues musicians and black listeners. However, despite Johnson’s stellar reputation within the Delta blues circuit, his music never reached a wide audience during his lifetime. During his brief recording career (which began approximately two years before his death in 1938), Johnson recorded twenty-nine songs. Of Johnson’s discography, only his song “Terraplane Blues” achieved modest commercial success during his lifetime.5

Despite Johnson’s small body of recorded blues, his “Hellhound on My Trail” (1937) is noted as one of blues music’s most terrifying songs, as well as a cornerstone of early blues music.6 In the song, Johnson agonizingly pines, “I’ve got to keep moving, I’ve got to keep moving, blues falling down like hail, blues failing down like hail . . . And the days keeps on ’minding me, there’s a hellhound on my trail.”7 Blues historians such as Robert Palmer (Deep Blues), and Johnson biographers,such as Elijah Wald (Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues), have interpreted “Hellhound on My Trail” in a variety of ways; however, the most popular interpretation is that the song evokes Johnson’s fabled deal with the Devil—a deal in which Johnson sold his soul in exchange for musical prowess.8 Per this interpretation, the hellhound featured in the song symbolizes the haunting presence of the Devil. While acknowledging that Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” is multivalent and that there are dangers in assuming that Johnson’s lyrics are real-to-life biographical descriptions, I will argue that the impetus and context for Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” may be partially biographical. Specifically, this essay’s premise is that Robert Johnson’s stepfather Charles Dodds’s near lynching and flight from the Mississippi Delta in 1909 is a plausible rhetorical context in which to understand the song. Rather than simply an ode to his deal with the Devil, Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” can also be understood as a lynching ballad that describes grassroots responses to lynching, such as flight and the anxieties that arise from perpetually fleeing lynch mob violence.

It is typically unwarranted and controversial to conflate the content of a song performed by an artist with their biography. In fact, Johnson scholars Jon Michael Spencer and Russell Banks argue that Johnson’s song lyrics are metaphorical rather than refer to actual lived experience.9 However, in the case of Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail,” it is plausible that the near lynching of his stepfather Charles Dodds inspired the song. According to Robert Johnson biographer Peter Guralnick, Johnson’s stepfather Charles Dodds was a prosperous wicker furniture maker and landowner in Hazlehurst, Mississippi. Local whites envied Dodds’s success and threatened to lynch him. Consequently, a white mob nearly achieved that goal; however, he narrowly escaped and fled to Memphis in 1909. According to blues enthusiast and folklorist Robert McCormick, a family legend developed concerning Charles Dodds’s near lynching. Apparently, the story went that Dodds was able to escape the lynch mob because he disguised himself in women’s clothing. Dodds lived in fear that he would be captured someday, so much so, that he changed his name to C. D. (Charles Dodds) Spencer in order to protect his true identity.10

When Johnson was between the ages of five and nine years old—from approximately 1914 to 1918—he lived in Memphis with his stepfather. However, after an unexpected encounter with his mother, Julia Major, on the streets of Memphis in 1918, he returned with her to the Mississippi Delta (near Robinsonville, Mississippi) and never again resided with his stepfather.11 Despite Johnson’s brief relationship with Dodds during his formative years, it is possible that Dodd’s brush with lynching helped inspire “Hellhound on My Trail.” There is no discussion among Johnson’s biographers of Johnson ever being chased or pursed by whites or the police, let alone a lynch mob. So the song is likely the product of Johnson’s imagination or an experience he heard about secondhand. While these inferences are plausible, and even tantalizing, neither information about whether Johnson knew the story of his stepfather’s near lynching nor his motivations for creating “Hellhound on My Trail” are known to history.

Even if Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” were not inspired by his stepfather’s near lynching, the song’s lyrics contain veiled references to lynching. To be sure, there were very few direct references to lynching—such as mobs, nooses, or hound dogs—in early blues music. Robert Johnson and other bluesmen may have omitted direct references to lynching because of the fear of violent reprisal or simply because they believed their audience did not want to hear songs about lynching.12 Nonetheless, literature professor Adam Gussow has convincingly argued that early blues songs such as Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” express a marked anxiety about being encircled by an invisible but ever-present lynch mob or some other terrifying menace. “The blues in this sense,” declared Gussow, “are a way of symbolizing what unconsciously oppresses the black blues subject—the ever-pressuring white gaze, periodic eruptions of ritualized mob violence, the blackened knuckles and pickled fingers strewn across the lynching South.”13

Perhaps the most vivid example of encirclement in early blues music is Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Hangman’s Blues.” In “Hangman’s Blues,” Jefferson pictures the hanging of a black man accused of murder. He sings,

Hangman’s rope sho’ is tough and strong,

Hangman’s rope sho’ is tough and strong,

They gonna hang me because I did something wrong.

I wanna tell you the gallis Lord’s a fearful sight,

I wanna tell you the gallis Lord’s a fearful sight,

Hang me in the mornin’, and cut me down at night.

Mean ole hangman is waitin’ to tighten up that noose,

Mean ole hangman is waitin’ to tighten up that noose,

Lord, I’m so scared, I’m trembling in my shoes.

Jury heard my case, and they said my hands was red,

Jury heard my case, and they said my hands was red,

And judge he sentenced me be hangin’ till I’m dead.

Crowd ’round the courthouse, and the time is going fast,

Crowd ’round the courthouse, and the time is going fast,

Soon a good-for-nothin’ killer is gonna breathe his last.

Lord, I’m almost dyin’, gasping for my breath,

Lord, I’m almost dyin’, gasping for my breath,

And a triflin’woman waitin’ to celebrate my death.14

While the song is not a protest song per se, it attempts to highlight the most appalling aspects of mob violence. Beyond protesting spectacle lynching, it calls to attention the white subject position for black listeners because spectacle lynchings took place in white spaces.15 For instance, the song describes how a white mob crowds around the courthouse to witness a black man’s execution, describes the white executioner who readies the rope for the hanging, and finally describes the anticipated emotional catharsis of a female mob participant who anxiously awaits the black man’s hanging. More importantly, though, Jefferson imagines the black hanging victim as overwhelmed by fear because he is encircled by a white mob without any possibility of escape.

In contrast, in “Hellhound on My Trail,” Johnson focuses on the black subject position because he endeavors to convey the psycho-emotional experience of the threat of lynching to black listeners. Johnson broods,

I got to keep movin’,

I’ve got to keep movin’,

Blues fallin’ down like hail,

Blues fallin’ down like hail.

Umm mmm mmm mmm,

Blues fallin’ down like hail,

Blues fallin’ down like hail,

And the days keeps on worryin’ me,

There’s a hellhound on my trail,

Hellhound on my trail,

Hellhound on my trail.

If today was Christmas eve,

If today was Christmas eve,

And tomorrow was Christmas day

If today was Christmas eve,

And tomorrow was Christmas day

(Aw, wouldn’t we have a time, baby?)

All I would need my little sweet rider just,

To pass the time away, huh huh, to pass the time away.

You sprinkled hot foot powder, mmm,

Around my door, all around my door.

You sprinkled hot foot powder, mmm,

All around your daddy’s door, hmm hmm hmm.

It keep me with ramblin’ mind, rider,

Every old place I go, every old place I go.

I can tell, the wind is risin’,

The leaves tremblin’ on the tree,

Tremblin’ on the tree.

I can tell, the wind is risin’,

Leaves tremblin’ on the tree, hmm hmm mmm mmm.

All I need’s my little sweet woman,

And to keep my company, hmmm hmm, hey hey,

My company.16

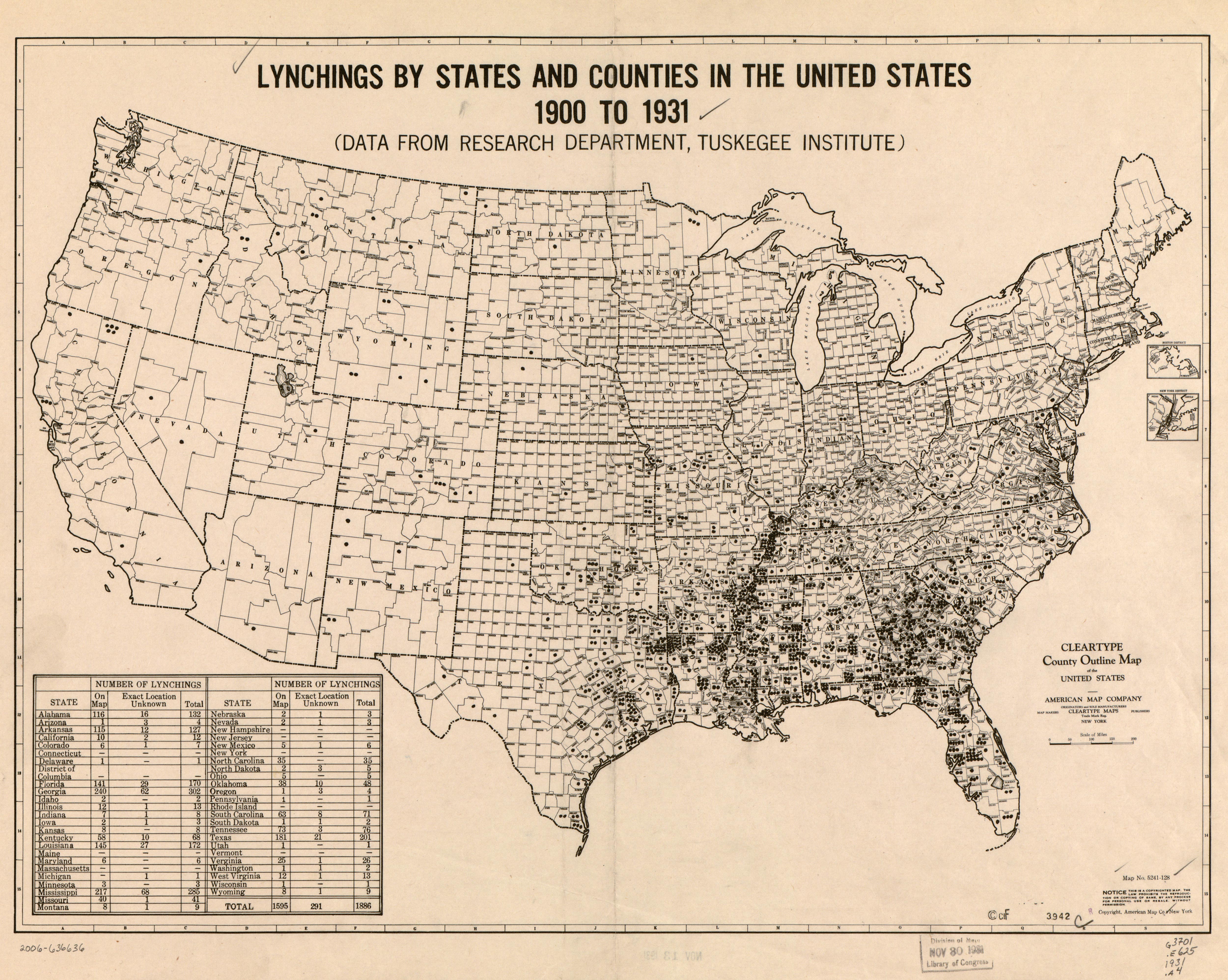

The hellhound is the song’s primary evocation of lynching, which can be interpreted as a veiled reference to bloodhounds that would have been used to identify the scent of a fugitive, a practice dating back to slavery. Johnson’s narrative seemingly revolves around a fugitive who has physically evaded a lynch mob that is signified by a hellhound; however, psychologically, he cannot escape the fear of encirclement. Johnson alludes to this point when he sings, “Blues fallin’ down like hail, / And the days keeps on worryin’ me, / There’s a hellhound on my trail” and implies that the lynch mob will perpetually pursue the fugitive until he is physically captured. Indeed, Johnson’s pessimism regarding the inevitability of capture was rooted in reality. Southern newspaper accounts of lynching abounded with stories of blacks evading white posses or police, albeit if only temporarily. For example, in 1921 Henry Lowery, a black farm laborer, allegedly murdered white planter O. T. Nelson in Nodena, Arkansas. Fearing that he would be lynched, Lowery fled over one thousand miles to El Paso, Texas. However, he was eventually captured, returned to Nodena, and burned at the stake after local whites intercepted a letter written by Lowery.17 To be sure, Johnson’s fugitive is never lynched nor comes close to being lynched. However, the fugitive always fears that he will be lynched. Johnson’s fugitive is so tormented that even the wind, trees, and leaves remind him of the lynch mobs’ pursuit. Thus, in important ways, Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” is about what it means to live in fear of lynching and the lynch mob.

Yet, “Hellhound on My Trail” contains more than veiled references to lynching. It also highlights grassroots responses to lynching. Similar to Johnson’s stepfather’s clandestine escape from white lynch mob violence, “Hellhound on My Trail” alludes to black flight and black social networks aiding black flight from lynch mob violence. For instance, as the narrative unfolds, it is apparent that Johnson’s fugitive has been provided shelter by his lover. However, it seems because the ever-pursuing hellhound “keep me with ramblin’ mind” and therefore he “got to keep movin’,” he is forced to flee his lover’s protection and the psychic escape it offers. Given the mental anguish precipitated by the seeming inevitability of encirclement, Johnson’s fugitive yearns for a psychic escape. Sex or specifically fantasizing about sexual fulfillment is the only thing that provides a temporary reprieve from the fugitive’s psychological torment. Consequently, Johnson’s fugitive fantasizes about reuniting and celebrating Christmas with his lover. Johnson’s anxiety about remaining with his lover and his eventual departure likely reflected the fact that many black lynch victims were often captured by posses in the vicinity of their family’s residence.18

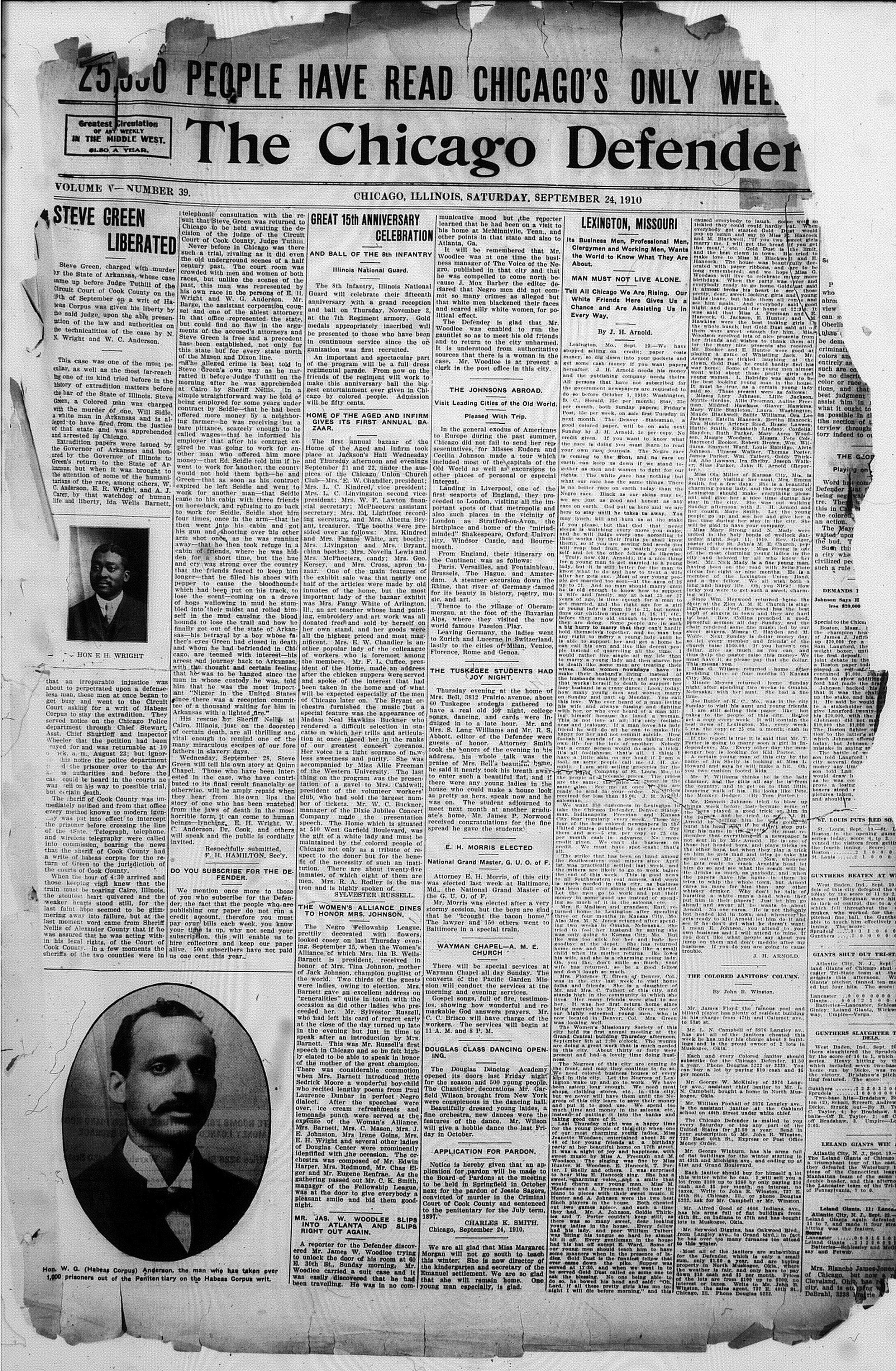

Also, the song more directly references black grassroots responses to lynching when it mentions black fugitives’ creativity in outsmarting their pursuers. Johnson’s fugitive mentions that his sweet little rider “sprinkled hot foot powder, mmm, / Around my door, all around my door.” Typically sprinkling hot foot powder is a reference to a hoodoo spell used for the purpose of “ridding one’s home of unwanted guests, removing unpleasant neighbors, and driving enemies away.” In certain contexts, it can also refer to placing a curse on an ex-lover.19 Given that Johnson’s fugitive is desperately attempting to physically and mentally escape the omnipresent threat of a lynch mob, the reference to foot power in “Hellhound on My Trail” likely describes the fugitive lover’s attempt to ward off a lynch mob. In fact, the reference to hot foot powder in “Hellhound on My Trail” describes black fugitives’ real-life attempts to stifle bloodhounds’ ability to track them to a specific location. For example, in 1910, Steve Green, a black tenant farmer, allegedly shot and killed William Sidel, a white planter nearby Marion, Arkansas.20 With a posse and bloodhounds on his heels, Green reportedly filled his shoes with pepper and wallowed in the mud in order to avert the bloodhounds. Miraculously, Green escaped the pursuing posse and made his way to Chicago.21

The story of Steve Green, read in conjunction with “Hellhound on My Trail,” painfully reflects the dilemma that black Americans faced. Blacks understood that they were trapped in a society that presumed their guilt. If they submitted to arrest or capture, the best they could hope for was a speedy trial that would most likely end in a state-sanctioned “legal lynching” or at worst they would be pursued, captured, and lynched by a mob of enraged whites who were intent on exacting sadistic punishment. For example, historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage argued that, in turn-of-the-century Georgia, forty-eight percent of blacks captured by posses never reached legal authorities and of those turned over to legal authorities twenty-eight percent were lynched before they were placed in jail.22 Even when white authorities offered a modicum of resistance to white lynch mobs, they were often overpowered by large and impassioned mobs. Given these options, blacks fled in order to save themselves from white mob violence.

The lynching blues, as represented in “Hellhound on My Trail” refers to being encircled by a white lynch mob. Johnson’s narrative depicts flight from white lynch mob violence as physically liberating but psychologically tormenting. This perspective was likely etched in Robert Johnson’s consciousness during childhood as he listened to stories of his stepfather’s successful flight. Johnson’s emphasis on being perpetually tormented by a hellhound suggests that his overall point was to stress that black fugitives could physically evade lynch mob violence but never psychologically detach themselves from the omnipresent threat. Despite the song’s obsession with the seemingly omnipresent threat of white lynch mob violence, its primary concern is not the inevitability of black victimization. On the contrary, it conveys blacks’ seemingly omnipresent fear of lynching as a means to highlight the way in which white terrorist violence forced blacks into a perpetual state of flight from lynching and implies that black social networks make possible black fugitives’ ability to physically escape capture. Indeed Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” is popularly regarded as an evocation of his mythic deal with the Devil, but given the song’s likely derivation, it should also be considered a musical exploration of his stepfather’s near lynching and, by extension, a psychological exploration of all black Americans who lived under the constant threat of white-on-black lynching during the era of Jim Crow.