1Introduction

Segregated lunch counters were one of the most visible sites of direct-action protest during the classical phase of the civil rights movement. In 1960 stalwart civil rights activist Ella Baker declared that the youthful protestors who participated in the struggle for desegregation acted out of much loftier goals than the desire for a “hamburger or even a giant-sized Coke.”1 Instead, she argued, the students who organized sit-ins at public dining venues throughout the South were concerned with nothing less than the “moral implications of racial discrimination for the ‘whole world’ and the ‘Human Race’” and not merely with their inability to fill their stomachs with an iconic food and beverage combination.2 In Baker’s formulation, southern racism was on trial. She saw food as incidental rather than fundamental to the struggle. However, by the close of the decade, many politically active African Americans regarded foods such as hamburgers as potent cultural symbols worthy of contemplation. Quoted in a 1974 article in Ebony magazine about a growing trend toward vegetarianism, African American blues musician Taj Mahal labeled a hamburger “a serious vulgarity.” In making that statement, he was articulating a belief then held by many.3

For some, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation at spaces of public accommodation such as restaurants, seemed like a mixed blessing. Although the demolition of legalized segregation was an important moral victory, passage of the law prompted questions about the desirability of meaningful integration. Radical African American food reformers did not always consider newly gained access to once-forbidden sites of public consumption a privilege. Instead, they saw integration as a potential liability to the southern black community.4 The right to participate on equal terms in American consumer capitalism began to seem less desirable to many who questioned the value of what Sarah Banet-Weiser has referred to as “consumer citizenship.”5 Some African American radicals came to consider the right to shop side by side with white Americans to be of dubious value, and some of the goods for sale in the American marketplace became a source of anxiety.

For some black nationalists, the meat that went into making Ella Baker’s hamburger was served alongside connotations of domination and violence, and the sugary Coca-Cola represented not only Americanization but also bad health.6 If hamburgers and Coca-Colas had—during the era of the sit-ins—been interpreted as symbols of citizenship denied, the renunciation of these items could later be understood as citizenship rejected. For protesters of this mindset, reveling in the right to consume American fast food on an equal basis alongside white southerners would have been seen as a manifestation of internalized racism and as a form of dietary malpractice.

Beginning in the late 1960s, an increasing number of black food reformers rejected, or at least complicated, what they regarded as standard American food practices. They asserted a separate black national identity and a competing value system. Culinary black nationalists did not conceive of food decisions as a series of trivial personal consumer choices but rather as an arena for communal activism. The construction of black nationalist foodways was both an evolutionary process and a dialectical one. Radical food reformers analyzed white-owned eating establishments and dominant American foodways in opposition to southern, regional cuisine and in contrast to a vegetarian-inclined diet.

2The Ascendency of Soul Food

In the aftermath of the civil rights movement many activists used food habits to reimagine their relationship to the U.S. nation-state. They embraced what Stephan Palmié has labeled “culinary identity politics” where “black collective selfhood” became rooted in a matrix of particular food practices.7 Jessica Harris claims that “eating neckbones and chitterlings, turnip greens and fried chicken, became a political statement” in the late 1960s.8 The origins of this trend stemmed from the transformations many younger civil rights activists underwent as they abandoned integration as a priority, instead emphasizing empowerment and race pride under the vague but seductive mantra of “Black Power.” During this era, proponents of what became known as “soul” endorsed cultural forms that epitomized what William L. Van Deburg has referred to as the “essence of the separate black culture” as exemplified in practices that demonstrated “in-group cultural cachet.”9 The term “soul” most famously referred to a genre of music. The descriptor was also used as a marker for other forms of cultural expression, such as distinctive hairstyles, clothing, and, of course, cuisine.

Proponents of “soul food” reimagined hybrid southern cooking—a product of African, European, and Native American ingredients and culinary knowledge—as a distinctly black cultural product, claiming that politically conscious African Americans should consume this cuisine alongside requisite doses of racial pride. By reframing southern cuisine as soul food, they claimed proprietary ownership of southern food culture. By transforming a regional style of eating into a racial one, African Americans living outside of the South could—if they wished—enjoy this food while still disassociating themselves from the place where white oppression had assumed its most totalizing form. The celebrated dishes in this style of cooking had direct antecedents in the foodways of enslaved people, and enjoying these foods mindfully could also become a way of celebrating the resilience of southern black people who fought total subjugation through expressive culture. Their diet had been built upon the cornerstones of corn and fatty pork, augmented with whatever they could grow or scavenge, including collard and turnip greens, black-eyed peas, sweet potatoes, fish, and small game, like opossums or squirrels.10 With the exception of the small game, which was consumed primarily in the rural South, these other ingredients became foundational elements in the soul food canon.

Many of the most vocal soul food supporters of the era engaged with southern food culture from vantage points north and west. Collectively, these sons and daughters of southern migrants who had fled the region seeking better job opportunities and less strident forms of racism maintained ties of culture and kinship to the South. For this group, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not dramatically alter the landscape of their daily lives—in contrast to those who remained in the South, where the outward signs of desegregation were dismantled. However, the law did inspire African Americans throughout the country to contemplate what a desegregated nation should look like. By extension, they imagined what members of such a society should eat. Regardless of what region of the country they lived in, during the Black Power era, politically conscious African American eaters had to come to terms with their relationship to traditional American food items as well as to those associated more closely with southern regional cuisine—and thus with slavery.

The ascendency of the concept of “soul food” imbued familiar foods with a politically charged valence. This rebranding left a permanent mark on the American culinary landscape. Fifty years after the phrase entered the popular vernacular, the term “soul food” persists to identify a particular cooking style. However, for some activists, the adoption of soul food was only a temporary ideological resting place on a journey toward greater culinary radicalism. A group of lesser-known activists, whom Frederick Douglass Opie labels “food rebels,” consciously rejected this food heritage. They characterized American food culture as unhealthful and corrupting, and, dismissed soul food as a pernicious rebranding of slave food.11 Many black nationalists urged African Americans to adopt a mostly vegetarian, whole-foods diet as a way to signal their rejection of the American values embedded in a painful past and as a means to improve the physical and financial health of the people they increasingly conceptualized as members of an oppressed, stateless black nation.

Some critics began their process of rejecting soul food by reformulating it as a diasporic, rather than distinctly southern, cultural invention. Now that the legal barriers to full inclusion into United States society were dismantled, black nationalists were free to consider the benefits of opting out of some aspects of American life. Forced marginalization had led to the creation and preservation of a distinctive black culture, and many activists channeled the energy they had used in civil rights demonstrations to celebrate a unique aesthetic in music, fine arts, literature, fashion, and food. Historian Kwasi Konadu explains the origins of this impulse, saying, “In the African diaspora, peoples of African descent do not have a state structure, so they root notions of nationalism in people and culture.”12

Part of conceptualizing diasporic people of African descent as members of a stateless, borderless nation meant constructing ideas of a shared food culture that was not rooted exclusively in the geographic space of the American South. Helen Mendes, author of the pioneering African Heritage Cookbook, proclaimed in 1971 that “Soul food unites African Americans not only to their people’s history, but with their contemporary Black brothers and sisters around the world.”13 Similarly, Vertamae Grosvenor’s concept of soul food was transformed as she discovered transatlantic culinary connections firsthand. In her landmark Vibration Cooking: Or the Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl (1970), Grosvenor recalled the excitement of exchanging recipes with a Senegalese woman she met in a Paris market. She was astonished to find similarities in dishes cooked on both sides of the Atlantic. This realization inspired her to look for African antecedents in familiar southern dishes like sweet potato pie.14 Others experienced similar epiphanies that shaped their understanding of the black culinary tradition. One African American traveler to West Africa in 1970 reported that eating “real soul food” on the continent “made us realize that our efforts at cooking here in America are very meager.”15

The menu at a Black Solidarity Day Celebration in Boston in 1970 similarly emphasized a transnational understanding of soul food, one laden with value judgments. Organizers promised a menu consisting of “African and colonized African (soul) food.”16 Presumably, the “African” food served at the festival could be dished without connotations of western culinary imperialism, but those who opted for “colonized African” foods would—the description implies—also be consuming a troubled history. It is unsurprising, then, that the acknowledgment of African origins often had the impact of displacing traditional southern foods from the black nationalist table. For soul food supporters, chitterlings and fried chicken were potent symbols of a distinctive black culture. Increasingly, however, a new kind of food activist pushed these items aside in favor of food imprecisely described as “African.”17 For example, a recipe vaguely labeled “Ghana Stew,” which appeared in the Oakland Post in 1972, was accompanied by the prophecy that readers who made the recipe—which consisted of beef flavored with tomatoes and nutmeg and served with cornmeal dumplings—“may never go back to neckbones and chitterlings.”18

The culinary black nationalists who consumed African-inflected soul food were influenced by and participated in the self-conscious work of cultural construction. Dietary concerns melded easily with the objectives of black nationalists who honed a distinct set of cultural practices, ostensibly of African origin, which would unite people of African descent across the globe. The food celebrated as southern soul food was clearly the cultural heritage of the descendants of enslaved Africans living in the United States. Diasporic soul food, on the other hand, was a culinary newcomer and a product of the late 1960s. The presumed direct gastronomic ties between the foodways of modern black Americans and of modern “Africans” (often construed quite broadly) were strained at best. For black food radicals, the invention of diasporic food was designed to meet present-day needs that demanded a degree of distance from slavery and more self-conscious ties with black people throughout the globe. Diasporic soul food could help fulfill these ideological needs and help create a new kind of black identity.

3The Construction of a Black National Food Culture

Maulana Karenga, one of the cofounders of the Organization Us, a cultural nationalist organization founded in California in 1965, was at the forefront of this movement of cultural creation. New African American attitudes about food habits were present in the first observances of Kwanzaa, an annual holiday that Karenga created in 1966, claiming that the antecedents of the celebration were African harvest festivals.19 Following his instructions, observers of Kwanzaa lit candles, gave gifts, and honored ancestors between December 26 and January 1. Each aspect of the holiday was carefully orchestrated. Observers greeted each other in Swahili and assembled ceremonial items such as a candle holder containing seven candles, each representing one of the Seven Principles (“Nguzo Saba”) of Kawanzaa. These principles guided the black community toward shared values such as unity and faith. Houses were to be decorated in red, black, and green, the colors of the African nation, and adorned with meaningful items like corn, designed to represent offspring.20

Early adherents of Kwanzaa were encouraged to fast from sunup to sundown to purify their bodies. Observers were instructed to think about the ritual significance of both consuming and abstaining from food. The fast was to be broken at sunset with only fruits, vegetables, and nuts. The period of abstention ended on December 31 with the Karamu, or feast, which was to include a meal in “the traditional manner,” consisting of “foods in the African style, and eaten without European utensils.”21 Despite Karenga’s justification of the necessity of the holiday and his instructions about many details of its observance, relatively little was written about the nature of the food to be served beyond the recommendation that it be “African” in origin. At the first Kwanzaa observance held in Los Angeles, attendees ate chicken, rice, black-eyed peas, and West African greens called jama jama, as part of a menu that invoked associations with southern-style African American cooking while also heralding a more diasporic understanding of black cuisine.22

The earliest Kwanzaa observers operated under the assumption that food behavior was an important factor in identity construction, but their prescriptions for proper eating habits were more impressionistic than the rigid codes developed by culinary nationalists elsewhere. Increasingly, the table was used for the dual purposes of acting out a Pan-African food identity and promoting beliefs about healthful living. In many nationalist circles, the idea of consuming “healthful” food became even more significant than the mandate to consume “African” food.

Despite that fact that health was a pressing concern for those involved with the task of nation-building, Clovis Semmes has demonstrated that the scholarly literature has not yet adequately explored this aspect of the black consciousness movement.23 Shared dietary ideas helped promote “group cohesion by providing a distinctive lifestyle, shared sacred beliefs, and a common moral order.”24 The increasing concern about the health value of foods made quintessentially American items like hamburgers and Coca-Colas suspect. It rendered many dishes on the soul food menu of dubious value as well.

Many cultural nationalists offered more concrete dietary prescriptions than the mandate to consume “African” food. They sometimes placed an even greater emphasis on foods that should be avoided rather than upon those that should be consumed. For example, the black-eyed peas served at the first Kwanzaa Karamu would have been considered anathema by Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam (NOI). He was perhaps the most outspoken proponent of a regimented, cultural nationalist diet. Muhammad proclaimed himself the “messenger of Allah” and dispensed the divine wisdom he claimed to receive on a variety of subjects, including proper eating habits, beginning in the 1930s. His advice about healthful living found new audiences in the late 1960s. Sympathizers could turn to his two-volume series How to Eat to Live, published in 1967 and 1972, to learn about the NOI’s strict food consumption guidelines. He also circulated his dietary teachings through the organization’s newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, which had a weekly circulation of at least 70,000 and likely reached even more readers through informal channels of exchange.25

Although Elijah Muhammad did not use the term “soul food,” Doris Witt has noted that he “intensified his condemnation of traditional southern black dietary practices as the popularity of soul food began to peak.”26 Unwilling to consider plantation foods a legitimate source of race pride, Muhammad urged his followers to cast off the “slave diet,” which the NOI believed was deleterious to the physical and mental health of the black nation. Following the convictions of orthodox Muslims, the NOI forbade the consumption of pork, which was labeled “a grafted animal . . . grafted from rat, cat, and dog.”27 However, NOI dietary restrictions went beyond the mandates of Islamic Halal and included many other items associated with the southern diet including collard and turnip greens, cornbread, sweet potatoes, and black-eyed peas. The NOI deemed these foodstuffs unfit for human consumption.28 To improve their health and to free themselves from the legacy of slavery, NOI members were ordered to shun foods associated with that dark past. Southern cooking was a materialization of the history of slavery, a troubled legacy that needed to be overcome. Dietary transformations, Elijah Muhammad implied, were linked to spiritual ones.29

Although the Nation of Islam had only about 20,000 members in 1966, the membership rolls alone do not capture the outsized influence the organization had on the black community. Most of the culinary nationalists of the era were heavily influenced by NOI teachings.30 No single intellectual figure had a stronger galvanizing impact on the Black Power movement in general than NOI minister Malcolm X, whose teachings were widely reported upon and discussed among politically aware African Americans. In 1964, Malcolm X traced what he regarded as the long-standing superiority of black food practices back to the beginning of civilization. He argued that Africans had always been more advanced than their European counterparts, and he urged African Americans to embrace racial culinary differences:

They didn’t cook their food in Europe. Even they themselves will show you when they were living up there in caves, they were knocking animals in the head and eating the raw meat. They were eating raw meat, raw food. They still like it raw today. You watch them go in a restaurant, they say, ‘Give me a steak rare, with the blood dripping in it.’ And then you run in and say, ‘Give me one rare, with the blood dripping in it.’ You don’t do it because that’s the way you like it; you’re just imitating them, you’re copying, you’re trying to be like that man. But when you act like yourself, you say, ‘Make mine well done.’ You like cooked food, because you’ve been cooking a long time; but they haven’t been cooking so long—it wasn’t too long ago that they knew what fire was. This is true.”31

Like Malcolm X, Muhammad also used meat consumption to differentiate black from white culture. He wished to separate the eating habits of his NOI followers from those of Christians, a category that presumably included not only white people but also black people who ignored his teachings. Christians, he claimed, were brutal and unenlightened in their methods of livestock slaughter, cooking, and food consumption. He argued that sufficient care was not taken to protect slaughtered animals from fear, evidence that they “actually murder the animals they eat.”32 Malcolm X agreed, claiming, “they’re blood-thirsty, they love blood . . . I’ve watched them; when I was a little boy, I lived on a farm with white folks. When they shoot something, they just go crazy, you know, like they were really getting their kicks.”33

In light of the association of meat eating with whiteness and brutality, it is unsurprising that Muhammad’s prescribed diet advised abstention from pork, a staple of the southern diet. Increasingly, he discouraged all meat consumption. Muhammad proclaimed that although eating other forms of animal flesh was not necessarily sinful, meat should be avoided for its lack of nutritional value. A vegetarian diet was deemed the most healthful and most virtuous way to eat.34 In light of his belief that white men were the original carnivores, he encouraged vegetarianism as a nationalistic decision. In the eschatology of the NOI, the white race would eventually die out, and meat eating would vanish with it.5

For the Nation of Islam, food practices were also an aspect of their program of economic nationalism. The organization urged members to pursue land ownership and to cultivate their own food. In 1971, a series of pen-and-ink drawings that depicted African American men and women producing their own food appeared in each issue of Muhammad Speaks. “Get Behind Muhammad’s Program,” a two-page spread that appeared in multiple issues, showed a large photograph of Elijah Muhammad against a landscape covered by orchards and populated with farm animals. Nearby were a factory that processed eggs and a black-owned cannery. Muhammad’s Program urged NOI members to pursue independent black foodways at the level of production, ensuring gastronomic separatism in every aspect of the food system.36 For Muhammad it was important that his followers adhere to his laws about food consumption in order to purify their bodies and to disassociate themselves from the food associated with slavery. However, these actions were only the first step in his radical program of nutritional self-sufficiency. Ideal nationalist eating practices began several stages before the dinner table with food grown and prepared by black people. The NOI founded Muslim-owned restaurants and grocery stores, purchased farmland, and even established a fish-importing business.37 For Muhammad, to reject Ella Baker’s symbolic hamburger was to opt out of American consumer culture in favor of the creation of a separate black economy.38

4Dick Gregory’s Radical Vegetarianism

Well-known comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory, like some members of the NOI, also emphasized the brutality of carnivorousness and questioned his own relationship to American consumer capitalism. Gregory had been involved in the southern sit-in movement and was arrested and jailed for participating in a sit-in at the Truckers’ Inn in Pine Bluff, Arkansas.39 In 1964 he and his wife, Lillian Gregory, were arrested while sitting in at a Dobbs House restaurant in Atlanta. Gregory confounded the management by announcing (truthfully) that he had purchased stock in the publicly traded company and could not be evicted from a restaurant he partially owned.40 Thanks in part to his efforts, African American residents of the city were granted equal access not only to hamburgers but also to dishes like “Mammy’s Fried Chicken,” a meal that invoked questions about the desirability of eating in racist, white dining establishments.41

Even after becoming a successful comedian, memories of an impoverished childhood still plagued Gregory when he began what he called his “Steak Career” of voracious omnivorism. He would go into a restaurant—such as the ones he helped integrate—and order “three, four, five, or six dinners—lobster, steak, chicken, pork chops and barbecued ribs in a single serving.”42

By the mid-1960s, participation in the civil rights movement extinguished Gregory’s appetite for animal flesh. His commitment to nonviolence as a tactic of protest and a value system convinced him that Ella Baker’s “bigger than a hamburger” claim told only a limited part of the story. He began to recognize a link between violence against humans and violence against nonhuman animals, noting that “Animals and humans suffer and die alike.” From 1965 onward, he “refused to accept that I had to stoop to the lowliness of killing something to get my dinner.”43 Similarly, Nick Fiddes has observed that, historically, meat consumption has been interpreted as a symbol of dominance and potency, “the ultimate authentication of human superiority over the rest of nature.”44 By associating the unequal power relationships embedded in American racism with the system of animal slaughter, Gregory connected his critique of meat consumption and his attempts to dismantle the existing power structure. His evolving system of food ethics led him to believe that by eating meat he was actually bolstering the forces of domination and oppression.

Eventually Gregory’s dietary reform initiatives became entangled in not only ethical but also corporeal concerns. What began as an answer to a moral question about whether or not nonviolent social protest and meat-eating could be integrated into a consistent belief system expanded into a quest for a healthier way of living. He abandoned a vegetarian diet after his weight jumped from 167 pounds as a carnivore to 288 pounds as a vegetarian who would “go into a soul food restaurant and wipe out the yams, greens, black-eyed peas, macaroni and cheese, corn bread, squash, dressing.”45 He soon came to believe that far from being a source of racial pride, “soul food” was deadly. He argued:

I personally would say that the quickest way to wipe out a group of people is to put them on a soul food diet. One of the tragedies is that the very folks in the black community who are most sophisticated in terms of the political realities in this country are nonetheless advocates of ‘soul food.’ They will lay down a heavy rap on genocide in America with regard to black folks, then walk into a soul food restaurant and help the genocide along.46

Gregory evolved toward a fruitarian, raw-foods diet, eating “only fruit, direct from plants and trees, in a natural state, fully ‘cooked’ by Mother Nature’s outdoor oven” and rejecting industrially processed foods.47 He and his wife, Lillian, raised their ten children following these dietary guidelines, and Gregory punctuated his eating program with periodic cleansing fasts.48 He was guided on his journey by African American naturopath Alvenia M. Fulton, who claimed, “If we human beings are children of nature, then it is to nature we must look for our health, welfare, and survival.”49 Like Gregory, Fulton worried that bad habits were deleterious to the health, proclaiming that “man’s tastes are so molded by his culture that they are useless to him as guideposts in nutrition. He must be taught what and how to eat.”50

Gregory enthusiastically promoted Fulton’s dietetics as an extension of his civil rights activism, believing that bad diets bolstered the forces of white supremacy by weakening or killing black bodies. Although Gregory’s strict fruitarianism inspired few wholesale converts, his commitment to maintaining the physical health of the black community was widespread in nationalist circles in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

5Cultural Nationalist Foodways in Newark and Brooklyn

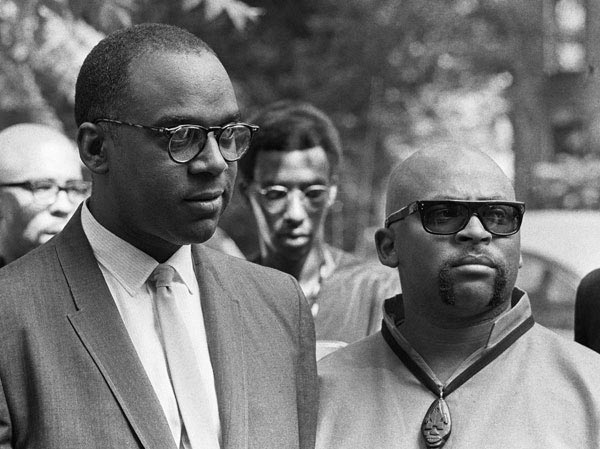

Amiri Baraka, one of the most influential activists of the era, has been frequently portrayed as a supporter of traditional African American foodways in the wake of his passionate 1962 essay titled “Soul Food.” Baraka hinted at what he regarded as the metaphysical properties of soul food when he answered a question about whether sweet potato pies tasted anything like pumpkin, saying, “They taste more like memory.”51 His poetic tribute to foods like hog maws, okra, and hoecakes has immortalized him as a defender of that diet, leading food studies scholar Doris Witt to label Baraka a “proponent” of black regional southern cooking in opposition to “detractors” such as Elijah Muhammad and Dick Gregory.52 Similarly, historian Frederick Douglass Opie contrasts Baraka and Muhammad, portraying them both as advocates for race pride who nonetheless had different concepts about proper food habits. Opie claims that Baraka “advocated soul food as black folk’s cuisine” in contrast to NOI “food rebels” who eschewed pork and other southern staples such as black-eyed peas.53 However, these generalizations obscure Baraka’s own culinary evolution throughout the 1960s.

By the end of the decade, Baraka and the other members of his Newark circle “did not eat meat, only fish, and otherwise were vegetarians.”54 Baraka, no stranger to personal evolutions, transformed himself from the Beatnik poet LeRoi Jones to Amiri Baraka, a central figure of the Black Arts Movement. He also evolved from soul food proponent to the leader of an organization that rejected traditional, southern food practices as harmful to communal health. Baraka went from praising soul food as “good filling grease” in 1962 to an asceticism that led him to give up alcohol and tobacco and to reassess his relationship to traditional African American cooking.55 His earlier embrace of soul food invoked racial pride in black cuisine. It also allowed room for the hedonistic pleasure of taste sensations. However, his new stance on dietary matters encouraged him to consider food choices as a matter of self-discipline. By putting dietary decision-making into the hands of the black leadership, culinary nationalists like Baraka sought to free themselves from the shadow of the slave diet that had been regulated by white oppressors. They did not reject the premise of hierarchy as much as they resented the fact that black dietaries had historically been as influenced by the white power structure as by black culinary volition. Baraka’s dietary turn sought to institute a new order and a new system of national culinary allegiances.

Although his ideological journey eventually shifted him out of the orbit of cultural nationalism into a race-conscious Marxist sensibility, in the late 1960s Baraka took inspiration from Karenga’s emphasis on cultural nation-building. Under the auspices of the Committee for Unified Newark (CFUN), Baraka joined Karenga in self-consciously creating cultural traditions that he hoped would foster a shared sense of identity. Theorists of the movement analyzed the relationship of the black community (which they labeled “Afrikan”) to the fine arts, to modern technology, and to various religious, educational, and political institutions.56 In position papers, Baraka and his collaborators made specific programmatic recommendations about how the black community should be organized, beginning with the family unit. Their patriarchal concept of the family emphasized male-dominated, heterosexual relationships and called for the performance of rituals to celebrate the creation of black families. Milestones such as marriage, the birth of a child, and death were to be commemorated in culturally specific ways, which included attention to the kind of foods served at these events.

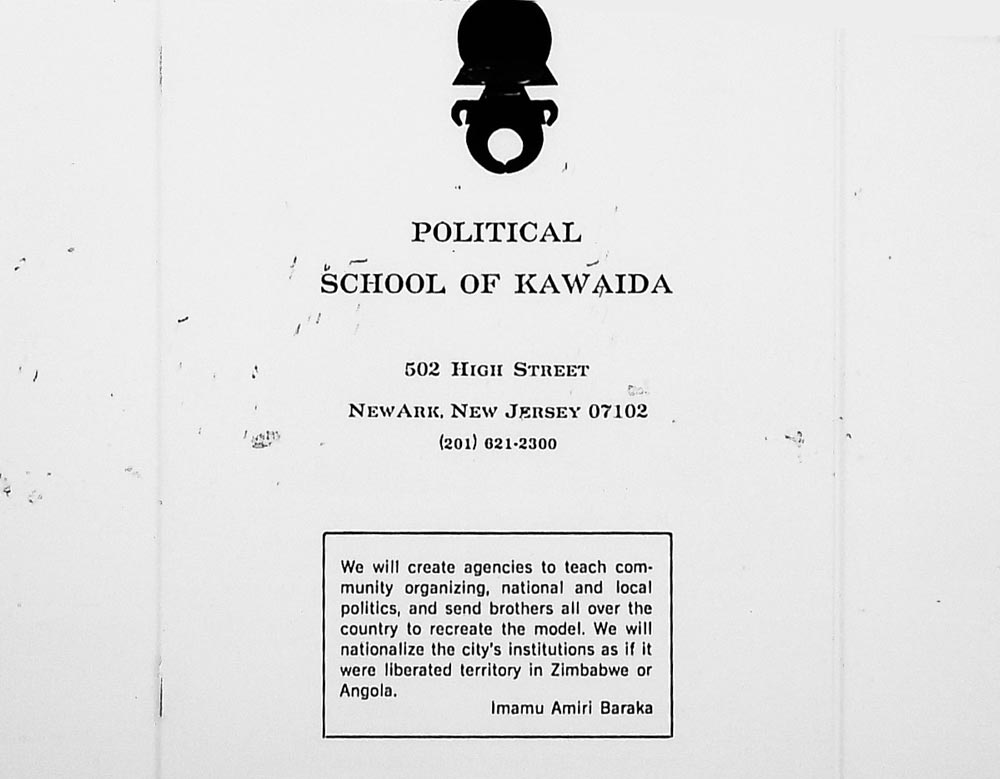

To teach these principles, Baraka led a “Political School of Kawaida” in Newark. Drawn from a Swahili word meaning “customs” or “systems,” kawaida referred to cultural nationalist values and rituals, which included ideas about food consumption. Baraka urged cooperative buying as a means to channel economic power and cooperative eating as an important ritual used to encourage group solidary. The ideal chakula (food) that was to be served at family or community gatherings consisted of vegetables, fruits, grains, fish and milk.57

Committee for Unified Newark sympathizers were to be careful about what they ate but were simultaneously instructed to avoid being perceived as too interested in dietary practices. They were told, “We are not fanatical about food but the national liberation of our people.”58 The message about food fanaticism may have been designed to distinguish Baraka’s followers from the members of the NOI whose famously rigid dietary rules were well-known in the black community. The confusing admonishment to be concerned but not obsessed about food practices was likely undermined by the number of references to food that appeared in the descriptions of member rituals.

Rites of passage and special holidays were all to be commemorated with specific food practices. On “Leo Baraka,” a community celebration of Amiri Baraka’s birthday, adherents were required to consume only fruit and fruit juice in observance of the day. Watermelon was to be served at the birth of a child, and at the Kuziliwa Karamu (birthday feast) fruit was again to be served along with “natural cakes.”59 Raw fruits and “natural” low-sugar cakes offered a dramatic departure from the flavorful meats, slow-cooked vegetables, and sugary desserts of the soul food tradition. These choices resemble aspects of Gregory’s fruitarian approach and are the outgrowth of similar ideas about health. Similarly, black nutrition guru Alvenia M. Fulton condemned white sugar as unwholesome, forbidding its use under all circumstances in favor of sweeteners such as honey.60

Following the lead established by US, Baraka’s adherents maintained a strict gender hierarchy, and the women in the organization bore the responsibility for cooking and serving food. They performed their tasks under a specific protocol, which stated that men should be fed before women “because respect and appreciation should be given to providers.”61 The CFUN charged women with the task of studying nutrition in order to feed, but not overfeed, their families. The organization’s literature instructed them to prepare meals that were largely vegetarian but could include fish. Nationalist women were warned against encouraging gluttony in their children, being told that overfeeding a child could lead the creation of a “greedy, selfish person.” Character flaws like these could not be tolerated, because the “Nationalist baby has a purpose.”62 Since the health and strength of black children was a shared national asset, members saw the proper feeding of children as a relevant issue for the entire black community.

Unsurprisingly, even outside the domestic sphere women continued to focus their work, at least in part, on food consumption. CFUN leaders instructed nationalist women to pressure school lunch programs to stop serving pork and sugar-coated cereals and to explore the possibility of cooperative food buying within the black community.63 Both the ideas about gender and the beliefs about food embraced by CFUN members resembled some NOI practices, indicating that the Newark nationalist community had likely been influenced by their religious teachings.

In addition, the ideas that the CFUN institutionalized in Newark were similar to those shared by a group of cultural nationalists living in neighboring New York City. The East, a community institution founded in Brooklyn in 1969, included an independent school, a performance space, cooperative businesses, and a newspaper, among other initiatives. Group members were generally in sympathy with the critiques of traditional food habits that had emerged in Newark.64 They rejected the paradigm of southern soul food and created a whole-foods diet that invoked the black diaspora with Swahili expressions. Instructions for feeding children given to the staff of the independent school, Uhura Sasa Shule, give clues as to the nature of the shared dietary rules of The East family. Children were fed meals consisting of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables and were forbidden to eat meat, dairy, or sugary foods.65 Adults, too, had ample opportunity to eat nationalist cuisine. The “Black Experience in Sound” hosted musical performances in an alcohol-free space where patrons could dine on dishes such as Kuumba Rice or East Punch from the popular East kitchen.66 Kawaida Rice, a popular vegetarian dish of brown rice, broccoli, mushrooms, and red and green peppers, drew its name from the term used to describe a distinctive black value system.67

Sales from the popular food served an important function in keeping The East financially afloat, and the success of the health-conscious cuisine inspired offshoot ventures including a catering company. A community-owned bakery showed that although both CFUN and The East were cautious about sugar intake, occasional indulgences were allowed. It served bean pie, a perennial NOI favorite, indicating ties of dietary sympathy between the organizations. However, the inclusion of sweet potato pie on the menu, an item condemned by Elijah Muhammad, signifies the limitations of this culinary convergence and illustrates that most partakers at the cultural nationalist table brought a broad range of dietary influences with them.68 For both the NOI and the members of The East, however, black foods were to be served by and for the black community. The Tamu Sweet-East bakery served food at “black prices,” endeavoring to make culinary manifestations of black culture affordable to the less prosperous in the community and freeing public food consumption from the taint of the capitalist marketplace.69

Members of The East, who referred to themselves as “family,” created a web of interlocking institutions and pledged themselves to mutual cooperation. Like CFUN, they adhered to Kawaida, core beliefs that adherents described as a “faith.”70 This value system was buoyed by many of the mechanisms associated with organized religion, including holidays like Kwanzaa and various written creeds. Male members of The East pledged to abide by the “Brotherhood Code,” which expressed a respect for Kawaida and mental, physical, and spiritual solidarity with the movement. Physical obligations included the vow to “observe dietary rules so that our functions are not hampered by illness.” Eating a whole-foods, vegetarian diet was important to maintain individual wellness and to insure the strength of the entire community. “When we are weak, the Nation shares our weakness.”71 For culinary nationalists, food decisions were a matter of community concern. Healthy black bodies belonged to the nation, they believed, and the failure to obey dietary rules could be seen as a form of community betrayal.

6The Dissemination of Dietary Advice

The values of the Newark and Brooklyn nationalist communities had much in common with those held by black activists throughout the country, indicating that dietary advice circulated regularly through cultural nationalist circles. In his classic The Destruction of Black Civilization (1971), Chancellor James Williams justified the focus on food as a significant issue for the black nation to address. He argued that “There is nothing mystical about the reasons why one group of people can easily become physically and mentally strong while another becomes physically weak and less mentally alert. An abundance of nutritious food and pure drinking water may spell the difference between advance and decay.”72

Johari M. Amini, a Chicago writer associated with the Black Arts Movement, was inspired by this observation and concurred that proper food habits were essential to the health of the black nation. In her pamphlet, Commonsense Eating: The Need to Become a Vegetarian, she argued that “Our survival as Afrikan people demands work…We must do more than merely ‘survive’. We have been doing that since we were brought to the western hemisphere. We must begin to live.”73 According to Amini, soul food had enabled the black community just to stay alive, while a more ethical and healthful vegetarian diet could enable the stateless black nation to thrive.

In 1970, when more than four thousand people from around the United States gathered in Atlanta for the founding meeting of the Congress of African People (CAP)—a nationwide organization inspired by the CFUN and organized under the intellectual leadership of Baraka—attendees discussed food reform in the black community as a key part of the post-civil rights political and cultural agenda.74 Declaring that it was “nation time,” CAP sought to focus disparate calls for black self-determination around a unified program and shared ideas about black culture. At the meeting, Reverend James Cone and Reverend Bill Land ran a workshop that explored religion in the nationalist movement. They articulated a theology that “teaches us no matter what we call ourselves (Baptist, Muslim, Hebrew, etc.) we are Black first, and all those other things next.”75

They urged members of the black nation to follow their strict dietary pronouncements, which included an indictment against foods similar to those eaten by enslaved people, a diet they labeled “garbage.” Although they gave a “wise Black woman” credit for making “hog guts” and other aspects of the southern diet palatable, they called for new food practices for a new era.76 They did not advocate for vegetarianism, but they did join the NOI in prohibiting the consumption of pork, shellfish, and catfish. They also condemned the consumption of animal blood and fat, deeming the already-maligned hamburger dangerous, due to the high fat concentration in ground meat.77 Cone and Land urged periodic fasting, both as an antidote to weight gain and as an opportunity to cleanse the body and to condition the mind. They warned that revolutionaries might face situations when they would have to go without food and urged CAP supporters to practice the discipline of denial in anticipation of potential future hardships.78 Food practices were to be centered on discipline, not on gustatory pleasure.

7Amiri Baraka’s Evolving Food Philosophy

Never intellectually intransigent or afraid to evolve ideologically, Baraka announced in 1974 that the Congress of African People would now embrace Marxism and reject Kawaida as an organizing principle.79 This change led to a less chauvinistic attitude toward the women in the organization and to the relinquishment of many of the ritualistic aspects of Kawaida that Baraka and others had so painstakingly created.80 For Baraka, who already had doubts about the emphasis on dietary practices, this change enabled him to justify easing those restrictions.

CAP’s ideological transformation led to the immediate resignation of Jitsu Weusi, director of The East, and of Haki Madhubuti, director of Chicago’s Institute for Positive Education. Baraka viewed their unwillingness to evolve as a betrayal, and he spurned Madhubuti for his insistence on clinging to cultural nationalistic eating practices. Although Baraka had a strong role in creating the dietary rules that came to be associated with Kawaida, those values became less important as he continued his political evolution. He accused Madhubuti of practicing a form of nationalism that “involves mysticism, e.g. the fanatical concern with the diet.”81 In addition, Baraka argued that it was hypocritical for Madhubuti to object to the philosophies of white people such as Marx and Lenin while he recommended dietary books written by J.I. Rodale and others Baraka considered to be “bohemians,” “food faddists,” and “petit bourgeois American whites.”82 Although Baraka still applauded the shared cultural nationalist impulse to give up pork as a means of “breaking down the slave culture that engulfed us,” he now argued, “Dressing up Afrikan and drinking distilled water and eating raw vegetables is not a revolutionary program.”83

For Madhubuti, food concerns remained at the heart of his conception of activism, and he continued to maintain that poor diets could be linked to various health problems in the black community. Although Baraka accused Madhubuti of hypocrisy because he had utilized books written by white health food advocates, Madhubuti’s shift toward vegetarianism happened within the context of black nationalism. Malcolm X’s decision to give up pork led Madhubuti to denounce all meat consumption.84 He decried meat eating as unhealthful and argued, “the North Vietnamese are winning a war and their major diet consists of organically grown rice and organically grown vegetables.”85 Madhubuti declared that an unhealthy diet was counter-revolutionary. He argued that an obese African person demonstrated a failure of self-control and lacked the energy needed to be an ally in the struggle to build a strong black nation.86 Suitable for the racially charged subtext of the indictment, Madhubuti urged cultural nationalists:

Stay away from anything that is white: there are no natural foods in nature that are white. Any food that is white is a mutation of the natural. Foods like white flour, white milk, white sugar, white corn meal and white eggs are dead food.87

8Vegetarianism Becomes Mainstream

The fact that Madhubuti’s library contained books written by white critics of contemporary food culture infuriated Baraka—who accused him of being arbitrary in his adoption or rejection of “white” social commentary—and indicated that nationalistic black vegetarians did not operate in cultural isolation. During this same era, a growing number of Americans from various backgrounds began to question the ethics of eating animal flesh. A 1975 article in the New York Times titled “Vegetarianism: Growing Way of Life, Especially Among the Young,” noted that the ascendency of vegetarianism was visible in the proliferation of vegetarian restaurants, a growing number of vegetarian foods available in grocery stores, and the increasing availability of meat-free options in college cafeterias. The article reported that the predominately white vegetarians featured gave up meat due to religious concerns and revulsion at violence and killing, ideas that they held in common with many black culinary nationalists.88

White vegetarians were more likely than black nationalist eaters to eschew meat due to guilt about the waste involved in meat production. While black culinary nationalists who advocated for less meat intensive diets pointed to the teachings of Elijah Muhammad, the activism of Dick Gregory, or the dietary recommendations made by the Congress of African People, whites who adopted a similar stance were more likely to call attention to Frances Moore Lappé’s Diet for a Small Planet (1971), which linked global food scarcities to the disproportionate amount of resources used for meat production.89 This segment of the white population wished to reverse changes in the food system caused by newer forms of intensive agriculture and to reclaim what they saw as a simpler, more pastoral way of life that had been displaced by technology. Historian Warren Belasco argues that for this group, “brown rice became the icon of antimodernity.”90 They believed that “mass-produced, processed food encouraged alienation from nature, society, one’s own body.”91

Black nationalist and white countercultural eaters used food practices as a way to demonstrate their disaffection with American culture, but they generally differed in their prescriptions for better alternatives. Proponents of what Belasco labels “countercuisine” developed a set of unconventional food practices as a way to establish identities on the margins of mainstream culture and to reject domination by a centralized power structure. White counterculture eaters did not propose an alternative national identity. In contrast, black nationalist eaters saw their food practices as an aspect of nation-building. They wanted to create a black nation that operated in lockstep, unified by ideological and cultural goals. Black culinary radicals used ideas about food as a means to opt out of white U.S. culture and into a black cultural nation.

Most African Americans in the 1960s were likely unaware of Baraka and Madhubuti’s dietary dispute, had not read Amini’s defense of vegetarianism, and were more likely intrigued than convinced by Gregory’s radical food politics. Nonetheless, critiques of mainstream food culture articulated by these and other black nationalist eaters helped inspire concerns about healthful eating even among African Americans who did not consider themselves to be either cultural nationalists or engaged political activists. Cultural nationalist prohibitions against eating pork, a belief that was common among all black radical eaters, had a tremendous influence on many segments of the black community. In 1970 Vertamae Grosvenor recalled making black eyed peas and rice “with beef neck bones instead of swine since so many brothers and sisters have given up swine.”92 A 1969 Ebony article, which conflated the food traditions of NOI members and orthodox Muslims throughout the Middle East, noted that “even black non-Muslims caught up in the current revolutionary mood are rejecting ‘the pig,’ either because it was the main meat served to slaves or because it is believed unhealthy.”93 A 1973 study that compared the food habits of black and white southerners noted a high degree of similarity between the two groups’ consumption habits but observed that black respondents were more likely than whites to label pork an unhealthful food.94 The idea that soul food was suspect impacted even those not self-consciously involved in the cultural nationalist project.

African American collegians were particularly open to new ways of thinking about dietary practices. In the October 1972 issue of Black Ink, the black student newspaper at the University of North Carolina, Gwen P. Harvey urged black students to quit eating the “greasy hamburger and french fries heaped on our plates with a mere shrug of the shoulder” and to scrutinize more carefully what they ate.95 In the December 1980/January 1981 issue of the Black Collegian, Ralph Johnson and Patricia Reed, students at the State University of New York at Old Westbury, echoed the teachings of the Elijah Muhammad when they complained, “Black Americans are under the illusion that their cultural food is soul food,” which they described as unhealthful, racist slave food.96 Frederick Douglass Opie estimates that by the late 1970s, about one percent of African American college students were vegetarians, and many more gave up pork or certain highly processed foods.97

Alternative food ideas influenced middle-class adults as well. In 1974 Ebony magazine declared a “Farewell to Chitterlings” and profiled a number of African Americans who had given up meat, mostly for health reasons. The article noted that, ironically, “some American blacks who can now afford filet have elected instead to dine on raw carrots and cabbage juice.”98 Florence Somerville, the food editor for the Chicago Defender, frequently printed vegetarian recipes in her column between 1972 and 1974. Her pronouncement that “vegetarian diets are exciting” was accompanied by a drawing of an anthropomorphized carrot scolding a sheepish pig. The carrot, depicted at one point as muscle-bound and lifting weights while standing next to a diminutive pig, appeared in her column several times as an ambassador for vegetarianism. Somerville’s recipes for curried spinach soup, eggplant pizza, and “Oriental eggs” did not invoke the soul food diet. Her recipe for “beefy green beans” calls for beef broth or bouillon. While not vegetarian, it did offer an alternative to traditional methods of seasoning vegetables with pork.99

African American eaters who wished to explore meatless options without radically altering every aspect of their diet could turn to Mary Keyes Burgess’s Soul to Soul: A Soul Food Vegetarian Cookbook, which appeared in 1976. Burgess became a vegetarian for health reasons as well as for Biblical ones after she learned about religious criticisms of pork consumption.100 She offered her readers the chance to have it both ways, to consume soul food while also embracing some of the dietary changes that were part of the cultural nationalist project. Burgess’s cookbook offered meat-free recipes for classic soul food items such as crackling bread made with artificial bacon and “fried chicken” made from processed soybeans. Her definition of “soul” offered a path of reconciliation for those who wished to celebrate the cultural ingenuity of southern African American food habits while maintaining a veneer of vegetarian moral nutritional superiority.

Burgess’s endorsement of industrially produced meat substitutes such as Worthington Stripples, Veja-links, and Skallops encouraged would-be conscientious eaters to combine their food ethics with a more concerted degree of participation in consumer capitalism. By the late 1970s corporate America was exploiting the concerns of conscientious eaters by marketing processed foods labeled “healthy” or “natural” to lure back consumers who had attempted to withdraw from the conventional food system.101 By the 1980s, the proliferation of mass-marketed alternatives to Ella Baker’s conventional hamburger meant that declaring culinary independence from the U.S. nation-state had become more challenging than ever for alternative eaters who were now left to ponder the ethical implications of not only the hamburger but of the soya burger as well.

9The Significance of Culinary Black Nationalism

Industrially produced vegetarian burgers represented a significant shift from the foodscape that Ella Baker invoked in her famous “bigger than a hamburger” admonition.102 Although the evolving critique of mainstream American foodways was not isolated to the black community, discussions about proper food habits took on a heightened significance when intertwined with the work of cultural nation-building. Food habits are always markers of identity and can be decoded to reveal much about the eater’s social, environmental, and cultural world.103 Sometimes these messages are embedded inadvertently in the habits of thoughtless consumers. Other times, as in the case of black nationalist eaters, food choices become a deliberate performance of a particular social role. Paradoxically, the action of following a dietary program was both a response to mundane, daily nutritional needs and a revolutionary activity. Nationalist eaters were faced with constant choices about how and what to consume. They could choose to identify with or to disavow their group identity with every meal, demonstrating that cultural nationhood consisted of a set of ongoing actions.

Conscientious eating practices were a way to signal cultural difference from outsiders. Black nationalist eaters could avoid meat as a way to demonstrate their rejection of the structure of white supremacy, which had been built on domination and violence. By consuming food produced by and for black people, radical food critics could distance themselves from American consumer capitalism. Particularized food habits were also part of the process of acculturation into the black nation. Cultural nationalists ate similar foods in a communal fashion in order to forge social connections and to enhance group unity. Food habits were also a way of reimagining a distinctly black corporeality. Some black nationalists were learning to view their bodies as group property and to think of health as a community concern. By avoiding sugar and other unhealthful foods, nationalistic eaters could demonstrate not only ideological fidelity but also physiological loyalty to the black nation. Food choices, one of the most quotidian manifestations of culture, provide a revealing glimpse into the felt experiences of these audacious cultural nation-builders. They believed that individuals had the power to transform themselves and their communities through everyday actions. They recognized that food is one of the most fundamental of human concerns and thus that few things are ultimately “bigger than a hamburger.”