Alumni Story: Presenting Southern Culture

This article, by Rebecca Lauck Cleary, was in the Winter 2016 issue of the Southern Register. Read the full Register here.

ALUMNI STORY: Presenting Southern Culture

These Southern Studies alumni are in very different professions, with one common thread: presenting southern culture to the public, whether it is through historic preservation, working in the visual arts, showcasing the correspondence of our third president, or helping artists and arts institutions with funding.

Kate Kenwright

Kate Kenwright works at the L’Enfant Historic Trust, a thirty-seven-year-old nonprofit that preserves and revitalizes historic communities in Washington, D.C. She received her BA in Southern Studies and also graduated from the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. She completed her Master of Preservation Studies Program at the Tulane School of Architecture. While attending Tulane, Kate interned with Longue Vue House and Gardens, Clio Associates, and the National WW II Museum. As part of her graduate studies there, she worked at the Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans where she participated in administering and monitoring easemented properties throughout the New Orleans area.

Kate Kenwright works at the L’Enfant Historic Trust, a thirty-seven-year-old nonprofit that preserves and revitalizes historic communities in Washington, D.C. She received her BA in Southern Studies and also graduated from the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. She completed her Master of Preservation Studies Program at the Tulane School of Architecture. While attending Tulane, Kate interned with Longue Vue House and Gardens, Clio Associates, and the National WW II Museum. As part of her graduate studies there, she worked at the Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans where she participated in administering and monitoring easemented properties throughout the New Orleans area.

What does your role as historic preservation specialist entail?

I work primarily with our Conservation Easement Program. A Conservation Easement is a voluntary legal agreement between a property owner and a qualified easement-holding organization where the property owner or owners promises not to alter the exterior of the property or surrounding open space without written permission from the easement holder. This gift to the Trust can qualify the donor for an income tax deduction. When an owner of one of our 1,134 easemented properties wishes to modify their historic building, I review their application and work with their team, which may include architects, engineers, contractors, and designers.

We also have our Historic Properties Redevelopment Program, which was launched in 2012. We acquired two blighted vacant historic homes, completed turnkey rehabilitations, placed a conservation easement on them, and sold them. So we not only save historic buildings that would otherwise be demolished because of neglect, we put them back into use and hopefully help revitalize the neighborhood in the process.

These two programs keep us busy, and in the true nature of a nonprofit, I can be doing any number of things in a day depending on what comes across my desk.

What drew you to the profession of historical preservation?

I studied architectural preservation because I believe in the importance of our shared cultural heritage, and this is my way of contributing to its protection. The built environment reminds us of where we came from and gives us a sense of our place in time. Buildings, particularly in the South, often act as symbols of identity. As our cities and landscapes evolve and change, the integration of the past into the future is of growing concern—something we studied extensively in the Southern Studies program. How to adapt and change in the face of technology and globalization without giving up the past or unduly glorifying it—this is a challenge shared by all who study and work in fields related to history and cultural heritage. In a more tangible way, the buildings that I work to protect are in D.C., which is technically in the South, even if it doesn’t always feel that way.

How does your Southern Studies degree help you in your job?

The Center teaches students to think differently. The interdisciplinary nature of the Southern Studies program, as well as the encouragement to approach everything with a critical eye, has really been of academic and professional benefit. I was encouraged by my professors to approach a problem in many different ways and to go to great lengths to get the necessary information, no matter how many archives you have to go to or people you have to track down. I deal with issues related to architecture, urban planning, preservation and conservation, art, history, and even archaeology on a daily basis. The ability to think outside the boundaries of traditional fields is so useful in this context.

We also learned at the Center to question who owns the past, and who gets to interpret it. In architectural preservation this lesson can be applied similarly—sometimes more ordinary buildings, including private homes, can be far more telling than the grand buildings that draw the most attention. Both deserve appreciation.

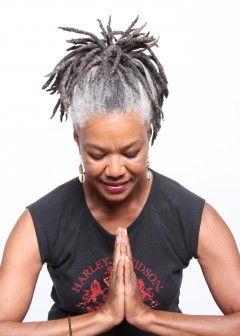

Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier

Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier is an Atlanta-based photographer, painter, and writer who has been documenting people and places of the South since 1989. She earned her MA in Southern Studies in 2005 and her thesis explored photography and community. She has won numerous awards, including a 2004 Lila Wallace-Readers’ Digest/Arts International Travel Fellowship, which allowed her to travel to Australia to document the aboriginal people of that region, and a Kellogg Foundation/Fulton County Arts Council residency in 1999 in South Africa to produce prints and document the dialogue between women from around the world on issues confronting the new millennium. Linnemeier’s work is in the Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, the High Museum of Art, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, among others. She also had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia in 2006 entitled Stereo Propaganda: Deconstructing Stereotypes, Reconstructing Identity. She currently teaches at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia. Her work Do what I say was chosen to be part of Atlanta Celebrates Photography’s 11th Annual Public Art Project.

Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier is an Atlanta-based photographer, painter, and writer who has been documenting people and places of the South since 1989. She earned her MA in Southern Studies in 2005 and her thesis explored photography and community. She has won numerous awards, including a 2004 Lila Wallace-Readers’ Digest/Arts International Travel Fellowship, which allowed her to travel to Australia to document the aboriginal people of that region, and a Kellogg Foundation/Fulton County Arts Council residency in 1999 in South Africa to produce prints and document the dialogue between women from around the world on issues confronting the new millennium. Linnemeier’s work is in the Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, the High Museum of Art, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, among others. She also had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia in 2006 entitled Stereo Propaganda: Deconstructing Stereotypes, Reconstructing Identity. She currently teaches at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia. Her work Do what I say was chosen to be part of Atlanta Celebrates Photography’s 11th Annual Public Art Project.

Tell me about your new project, The Other Side of Zora Neal Hurston’s Eatonville, and how you came up with the idea.

The project gathers photographs from residents of Eatonville, Florida, to be included in an agan, a masquerade costume worn during an Egungun masquerade. I build facsimiles of these structures. I engage the community on many levels. Children do cyanotypes on fabric that are sewn into the artwork, and elders generally lend photographs. Elders and some children also help with sewing the pieces together. I was invited to do this project by curators Jerushia Graham and Lonnie Graham. I met Lonnie Graham at Manchester Craftsman’s Guild, a community-based facility back in the 1990s and knew Jerushia through her work in the community here. Lonnie is a photographer and Jerushia is a printmaker. The end result will be an installation at the Zora Neale Hurston Museum in Eatonville.

William Bland Whitley

William Bland Whitley earned his Southern Studies MA in 1996 with a thesis titled “Shades of White: Party Politics in Mississippi, 1870–1896.” He works at Princeton University as associate editor of the Thomas Jefferson Papers, which began as an outgrowth of a congressional mandate to the Thomas Jefferson Bicentennial Commission to consider the feasibility of a comprehensive edition of Jefferson’s works. That enterprise was launched in December 1943 and continues today with a digital edition, started in 2009.

What kind of work do you do?

I’m helping publish a comprehensive edition of the correspondence and other unpublished writings of Thomas Jefferson. We are publishing, or at least accounting for, all of the letters Jefferson wrote and received, as well as other documents like memos, notes on meetings, and invoices. Thus far, the project has brought out forty-one chronologically organized volumes (thirty-eight of which are also on the web), with three more actively in production. We publish about one volume a year and expect to finish in about ten years. My work involves a variety of tasks, the most important of which involve verifying that our transcriptions of individual documents are as accurate as they can be and annotating the documents to bring to light information that might be useful to readers. I spend much of my time doing nitty-gritty research for annotations that identify correspondents, explain obscure references, or connect aspects of the documents to larger historical issues—all with the objective of making the documents more comprehensible.

How does having a background in Southern Studies help you?

Southern Studies helped prepare me for my current job because it encouraged me to get excited about a wide range of topics. At the Center you’re never confined to one approach or disciplinary silo, and you are exposed to cool little corners of southern culture. Anything and everything can be important and interesting. That’s an approach I try to take in my current work, and it comes in handy, too. Jefferson was conversant with so many subjects and attracted a wide array of correspondents, both accomplished and humble. The experience of juggling a number of different subjects and approaches has certainly helped.

Turry M. Flucker

Turry M. Flucker is a native of Houston, Texas. Before becoming the arts industry director at the Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC), he served for nine years as branch director at the Louisiana State Museum, directing the Louisiana Civil Rights Museum Project. He also served as the curator at Smith Robertson Museum in Jackson, a position he maintained for ten years. He earned his MA in 2014.

Turry M. Flucker is a native of Houston, Texas. Before becoming the arts industry director at the Mississippi Arts Commission (MAC), he served for nine years as branch director at the Louisiana State Museum, directing the Louisiana Civil Rights Museum Project. He also served as the curator at Smith Robertson Museum in Jackson, a position he maintained for ten years. He earned his MA in 2014.

Tell me about your job as arts industry director at the Mississippi Arts Commission.

I work with large performing arts and single-discipline organizations, such as museums, operas, symphonies, theaters, and film festivals, across the state. These organizations apply for operating and programmatic support, and I manage the grant applications from start to completion. I also manage fellowship applications for visual artists, the applications for the visual artists’ roster, and the mini grants for individuals and organizations. I also work with the Mississippi Presenters Network, a statewide network of small, medium, and large presenting organizations.

How do you utilize your Southern Studies degree at MAC?

I am one of the hosts of the Mississippi Arts Hour on MPB. It’s a weekly radio show that focuses on what’s happening in the arts and cultural comminutes throughout the state. Each week we interview artists, musicians, other arts administrators and curators. I approach each interview as if I am doing an oral history, with Mississippi as the backdrop. It’s about place and how place shapes the work that they do. I learned to listen and observe more in Southern Studies. That experience has helped me tremendously, not only in doing the Arts Hour interviews, but also as I work with grantees and other constituents that we serve. Pursuing a degree in Southern Studies was one of the best life decisions that I ever made. To the study the American South is to study America and the rest of the world.